Danny Noonan

Smails bullies, then acts fatherly towards Noonan

This is the fifth installment in a series of posts offering a semiotic analysis of the 1980 golfing comedy Caddyshack. (Why select this particular, not very successful, deeply flawed movie? See the series introduction.)

In this series’ second installment, I introduced SEMIOVOX’s G-Schema, a purpose-built tool that I’ve developed (over the past 20+ years) in order to productively and insightfully map any product category’s, cultural territory’s, or cultural production’s network of meaningfulness. In constructing each new G-Schema, I proceed in a tried-and-true fashion — the idiosyncratic methodology of which this series aims to demonstrate.

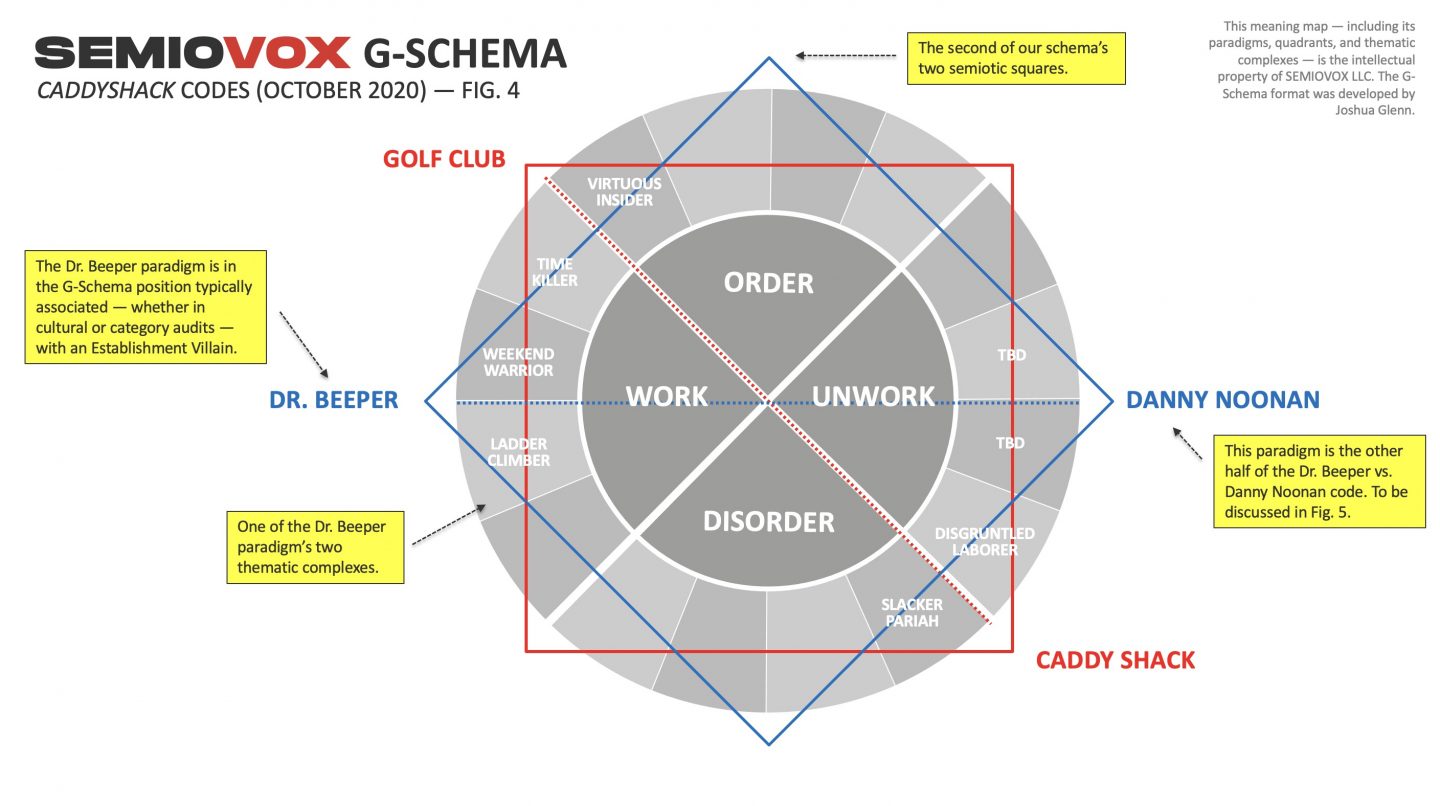

By the end of this series’ fourth installment, we’d arrived at the mapping stage illustrated in Fig. 4 (above). As you can see , we’ve now completed our analysis of the paradigm Dr. Beeper, having surfaced and dimensionalized the source codes (“signs”) that bring its two thematic complexes to life. In this post, we’ll look at Dr. Beeper’s opposing paradigm: Danny Noonan.

Paradigm

As Fig. 4 indicates, the paradigm that I’ve named “Danny Noonan” governs the Caddyshack meaning-map’s UNWORK quadrant. I’ve titled this quadrant UNWORK because, as this series demonstrates, a resistance to the dominant discourse’s “work idea” can take many forms, from slacking to idling (not the same thing, as Mark Kingwell and I argue in our 2008 book The Idler’s Glossary) to the two sorts of unwork of which Noonan is this movie’s avatar.

In my experience, the term located at a cultural-production G-Schema’s far-right vertex is almost always a Rebellious Hero, of one variety or another. Danny Noonan, the rebellious hero of Caddyshack, feels pressured to work or worm his way into the Establishment — represented by Bushwood in general, and Dr. Beeper in particular. As noted in the previous installment in this series, Dr. Beeper represents everything that Noonan does not want to become. If Noonan were to internalize the dominant discourse’s work idea, and diligently make his way through college and professional training, he could become a Beeper — which is to say, a ladder climber and weekend warrior. In this Hesse-like Bildungsroman, however, Noonan will in the end reject this shibboleth towards which we’ve watched him fitfully advancing.

NB: Those readers interested in storytelling will have already noted that, according to my G-Schema, the villain isn’t directly aligned with the oppressive culture, nor is the hero directly aligned with the counterculture. In any cultural production sufficiently complex to merit the sort of meaning-mapping that I do, it’s always more complicated than that.

Michael O’Keefe, who plays Noonan, was nominated in 1980 for an Academy Award for his portrayal of the character Ben Meechum, the sensitive son of the macho, combat-damaged Marine pilot Robert Duvall, in The Great Santini. Although the Newsweek review of Caddyshack would complain that the movie’s writers had “saddled themselves with a bland hero,” this was fortuitous. Let other Caddyshack characters — Ty Webb, Carl Spackler, Al Czervik — disrupt Bushwood’s repressive tranquility and decorousness. O’Keefe’s role here is — as it was in The Great Santini — to bear witness, sensitively, to the unpleasantness of becoming an adult male. Because he’s “fuzzy,” to use McLuhan’s terminology from Understanding Media (1964), which is to say undefined, still developing as a human being, the viewer engages sympathetically with Noonan. We root for him not to blow up the golf course, but to stick up for himself, to survive adolescence.

Adapting and building upon the terminology of C.S. Peirce’s existential graphs — a c. 1903 diagrammatic system to represent “the fundamental operations of reasoning” — we’d describe the Danny Noonan categorical proposition like so: “It must not be the case that Caddy Shack is Golf Club.” The two paradigms flanking Caddy Shack, on our diagram, are not entirely persuaded by that paradigm’s counter-discourse; unlike the slackers of the Caddy Shack, then, they are driven to combat the Golf Club’s ideological apparatchiks; in Danny Noonan’s case, the direct conflict is with Dr. Beeper.

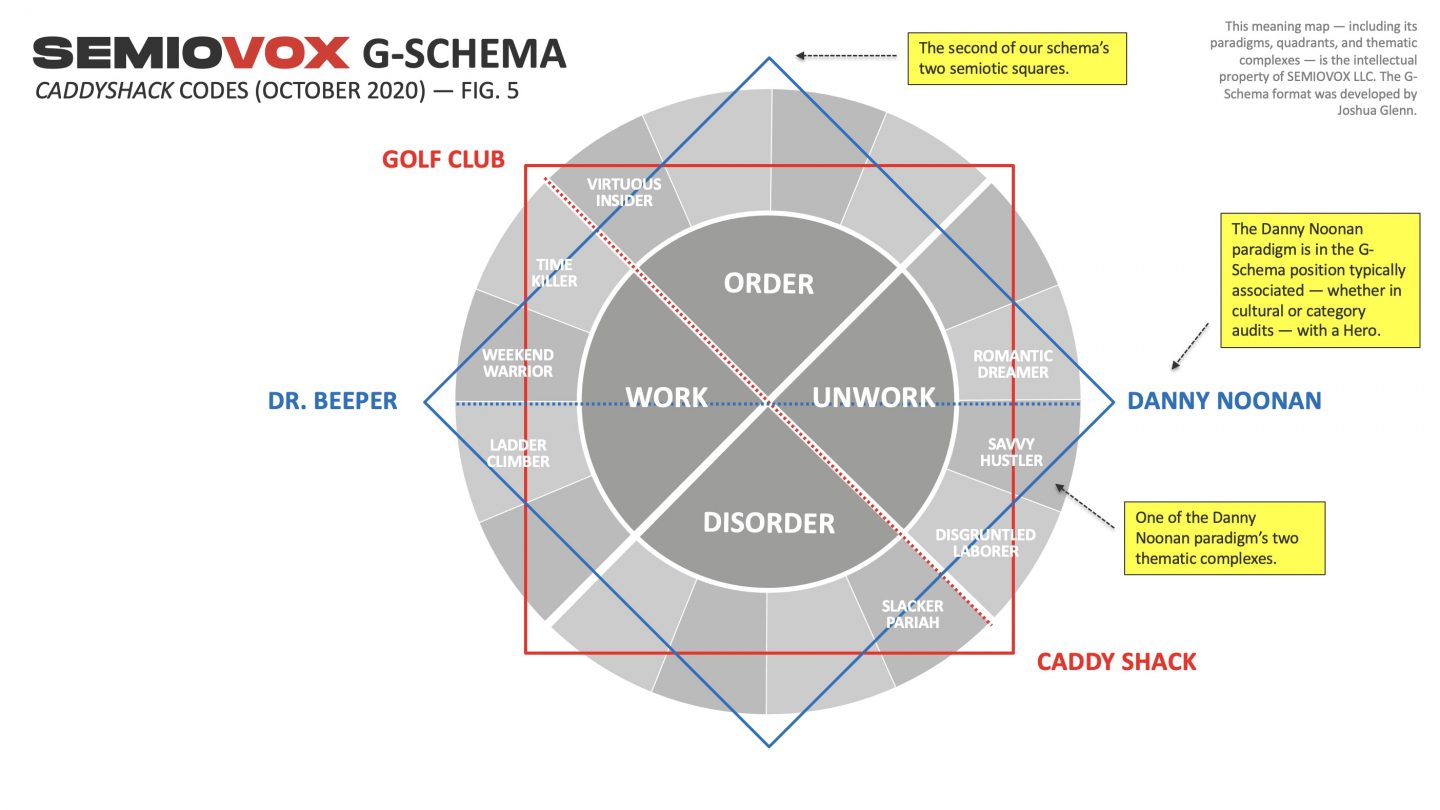

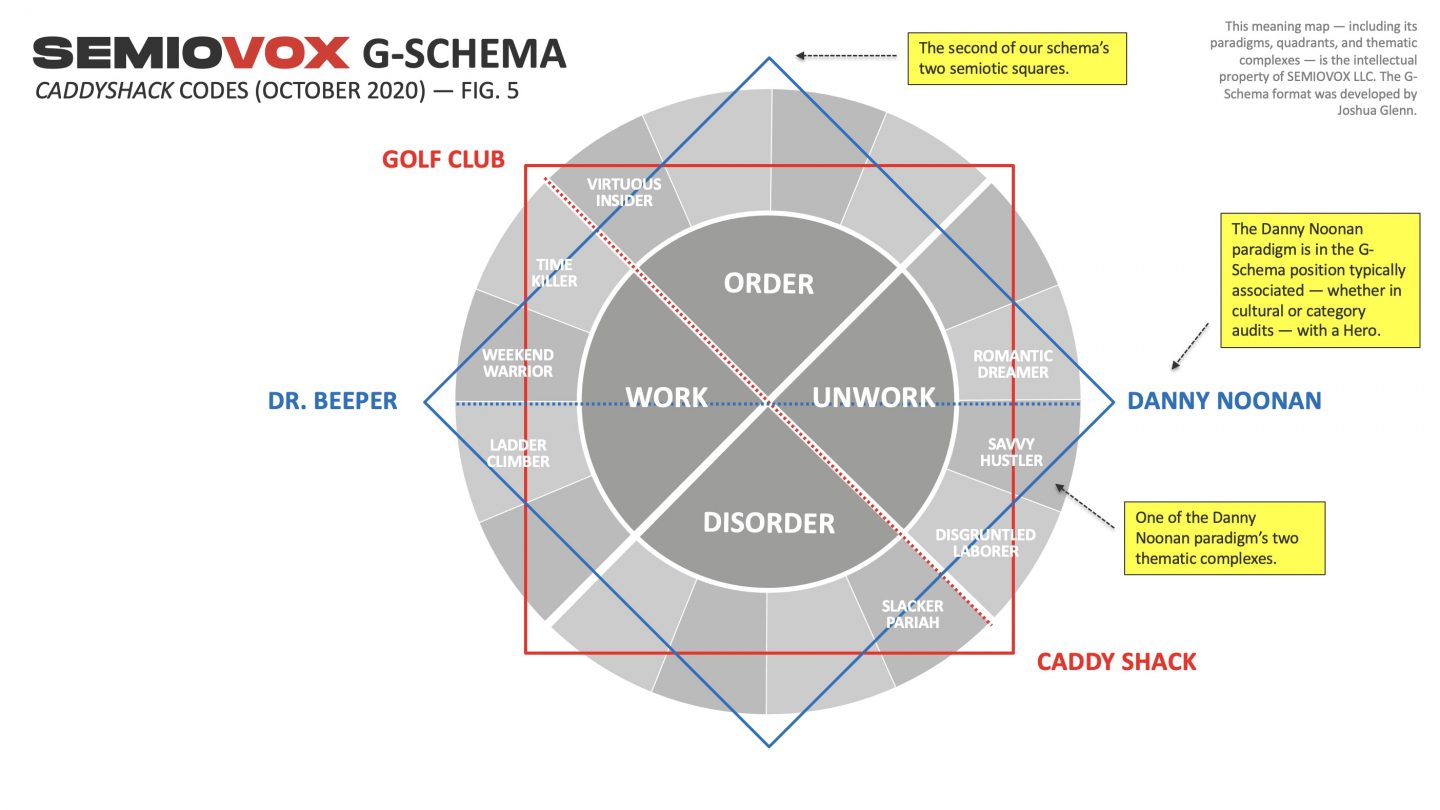

We’ll turn now to an investigation of the paradigm Danny Noonan’s two thematic complexes. According to my analysis, as Fig. 5 (above) demonstrates, the thematic complexes Savvy Hustler and Romantic Dreamer are central to this semiosphere’s UNWORK quadrant.

Savvy Hustler

As mentioned when we analyzed the paradigm Caddy Shack, Danny Noonan is not a slacker. In fact, he’s a diligent — if disgruntled — laborer, who works long hours over the summer in order to pay for college. However, when he spots a less arduous opportunity to worm his way into the Establishment, via a college scholarship for caddies, another aspect of the UNWORK quadrant is revealed. Noonan becomes a savvy hustler.

According to Chris Nashawaty’s 2018 book on the making of Caddyshack, the movie’s director, Harold Ramis, originally leaned towards casting Mickey Rourke (who was 27, or three years older than O’Keefe at the time) in the Noonan role. Had they done so, Caddyshack would surely have become more of a streetwise con-artist movie: Think of Rourke’s small part in Body Heat 1981) as an arsonist, or the wised-up characters he’d play in Diner (1982), Rumble Fish (1983), and The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984). Fortunately for Caddyshack fans, Michael O’Keefe was cast instead. “He seemed like a real person,” Ramis has since said. “Maybe too real.”

We’re informed that Noonan is an independent, maverick type early on. As he leaves home by way of the fire escape (3:24), the Kenny Loggins theme song announces, “I’m alright / Nobody worry ’bout me.” Indeed, we’ll see him hustle, in small but telling ways. For example, Maggie sneaks him free food (26:08) from the snack shack; and earlier, his parents castigate him for squandering his caddying tips on Cokes. Although Maggie is an industrious laborer, Danny isn’t; when she encourages him to bus tables at the 4th of July gala, he says, “I don’t think I can handle that” (26:22). He does end up bussing tables, that night, but we understand that he does not see himself as someone who will get ahead in life by working his way up from the bottom.

When Lou Loomis announces that there’s a college scholarship to be won, Noonan seizes the opportunity. Despite being mocked as a brown-noser, he volunteers to be the Judge’s caddy — a gig to be avoided, we’re led to believe, since the Judge cheats, bullies his caddies, and is a lousy tipper. And brown-nose he does, taking one big swing after another. When Smails fumes — about Czervik’s antics — that “music is a violation of our personal privacy” (22:25), Noonan suggests that he’s often thought of becoming a lawyer who specializes in exactly this sort of thing. Smails’s unimpressed response, another of Ted Knight’s great line deliveries: “Well, the world needs ditch diggers, too” (23:10).

This is humiliating stuff, as Noonan is observed not only by fellow caddy Motormouth but by Lacey Underall — both of whom tease him — “I’ve often thought of becoming a golf club” (25:27) — for his clumsy efforts to ingratiate himself with Smails. PS: Motormouth, one now understands, after watching the movie many times, is Jiminy Cricket to Noonan’s Pinocchio.

However, after throwing his golf club in a fit of pique, thus injuring a Bushwood member, Smails gets into a pickle — and the quick-thinking Noonan doesn’t hesitate to capitalize on the situation. Taking blame for the incident upon himself (27:38), Noonan finally gets himself onto Smails’s radar. Sitting down together, Smails mentions the scholarship, Noonan mentions his poor grades, and Smails suggests that there are more important things than grades — such as winning the caddy tournament (28:20). Ted Knight’s exaggerated facial expressions provide subtitles for this exchange. They don’t shake hands, exactly, but there’s a handshake-like moment when Smails gives Noonan his (lousy, as expected) tip. Smails, unsure of himself when they first sat down together, has succeeded in gaining the upper hand once more; Noonan has become his protégé.

There’s no hustling going on, per se, during the caddy golf tournament — but through his victory, Noonan demonstrates, to Smails, who as we’ve seen judges his fellow men by their golf handicaps, that he has the right stuff. The outfit he wears during the tournament is also an aspect of his brown-nosing campaign. Whereas his rival D’Annunzio tees off in a silk shirt (while smoking a cigarette), Noonan is dorky in his tucked-in polo and chinos (40:26). He looks like a preppie; worse, he’s a wannabe preppie.

PS: As noted in this series’ Dr. Beeper installment, although Noonan manages to win the tournament, it’s not because he’s a weekend warrior — e.g., spending his down time improving his stroke, or tightening up his short game. In fact, we never see him practicing golf. It’s not as though he and Dr. Beeper, the villain to Noonan’s hero, secretly have something in common. Noonan is naturally athletic, and he knows how to keep his cool.

Invited to Smails’s yacht club, after he does some yard work for Smails, Noonan shows up in an even more embarrassing outfit: an ill-fitting blue blazer with gold buttons and a white yachtsman’s cap, which were no doubt scavenged from the club’s Lost and Found assortment of castoffs. Mocked by the Yacht Club’s teenage set, Noonan seeks the protective camouflage of older and younger members — among whom his outfit does not stand out. There’s also a funny moment (54:47), when Smails notices that Noonan and he are dressed exactly alike; Danny’s apery makes Smails look foolish.

At the yacht club, we’re briefly introduced to Chuck Schick (Scott Jackson), a law student who is clerking for Smails. Chuck is wealthier and better-educated than Danny, a well-bred preppie against whom he cannot compete. Trying to make small talk with the supercilious jerk (54:50), Noonan says, “Well, I’m going to law school, too.” “Really? You going to Harvard?” asks Chuck, literally looking down his nose at Danny. “No, St. Copius of northern, uh…” “Where?” asks Chuck. Danny finds himself out of his depth.

Luckily, Lacey swoops in to rescue him, dismissing her uncle’s law clerk, who moments earlier was assiduously massaging her feet, with a “Bye, Chuck!” (55:10) If this were another movie, Chuck would have played a larger role as Danny’s rival for Lacey’s affection and Smails’s esteem. Here, however, he vanishes immediately. His brief role was merely to provide a contrast to Danny, at the yacht club — he’s a privileged kid who doesn’t need to hustle.

Things will go sideways for Noonan, shortly after this moment of triumph — as we’ll discuss in the Romantic Dreamer section of this post. However, the following morning he’s given another opportunity to get into Smails’s good graces and secure his grasp on the elusive caddy scholarship. This involves a certain amount of toadying on Noonan’s part. In Smails’s office, he allows himself to be bullied and lectured to, before announcing “I want to be good,” and fake-laughing at Smails’s heavy-handed humorousness. It’s all very reminiscent of the moment when George Bailey nearly accepts a position working for Old Man Potter in It’s A Wonderful Life — including the creepy handshake moment (1:08:59), when Noonan looks at Smails’s hand with a certain fear and loathing before taking it: “Yes, sir. I’m your pal.”

This trajectory of Noonan’s, hustling his way towards a free ride to college — even though he doesn’t really want to attend college, or be a lawyer — culminates in Noonan’s caddying for Smails instead of his true mentor, Ty Webb, in the money match. Which involves helping Smails cheat. When Czervik drops out of the match, and Ty invites Noonan to take his place (1:26:32), it’s a momentous moment. When Noonan says, “I’ll play” (1:26:53), it’s reminiscent of George Bailey’s rejection of Potter’s creepy offer of friendship and sponsorship. (“You sit around here and you spin your little webs and you think the whole world revolves around you and your money. Well, it doesn’t, Mr. Potter. In the whole vast configuration of things, I’d say you were nothing but a scurvy little spider!”) A moment of moral clarity.

One final note, before we move on. As Fig. 5 (above) indicates, the Savvy Hustler thematic complex is adjacent to our meaning-map’s Disgruntled Laborer complex. Just as we found a continuum within the WORK quadrant (from more to less leisurely, or less to more), as we study the UNWORK quadrant’s complexes we’ll also find a continuum of attitudes towards work and the work idea, and a continuum of practices shaped and guided by those attitudes. Whereas the disgruntled laborer is a Stakhanovite, who shrugs and works harder when ordered to do so, the savvy hustler looks for a way to beat the system. Other complexes within UNWORK, as we’ll see, involve different approaches to dealing with the work system.

Romantic Dreamer

Unlike the Savvy Hustler thematic complex, the Romantic Dreamer complex doesn’t valorize beating the system from within, playing the angles, keeping an eye out for the main chance, and so forth. It’s an idealistic, even quixotic complex. Less favorably, we might also regard this as an entitled complex; to daydream about a castle in the clouds (or tony suburb) is to harbor a not-so-sneaking suspicion that you are a naturally superior sort of individual.

Movies about savvy hustlers who beat an unfair system are fun — but Caddyshack isn’t only that sort of movie, and our rebellious hero isn’t only a rogue, flimflammer, or grifter. As the movie’s opening credits roll, Danny Noonan pedals his ten-speed — literally, from the “wrong” to the “right” side of the tracks (3:40) — to Bushwood. Admiring the stately homes as he pedals past them, we can see from the glazed expression on his face that he fantasizes about living in one of them, one day.

Kenny Loggins’s theme song, meanwhile, explains what’s going on Noonan’s head: “Who do you want [to become]? / Who you gonna be today? / And who is it really / Makin’ up your mind?” Noonan is “some Cinderella kid” (another line from the song), which is to say a romantic dreamer who wants to become something other than he is — not by hustling, nor through labor, but by listening to his “own heart beatin’.”

In the movie’s following scene, Noonan seeks counsel from Ty Webb — earnestly enquiring whether the feckless prepster has ever had trouble deciding what he wanted to do with his life. Noonan’s lost-ness, his status as an existential drifter, by the way, is communicated here via the haunting cinematography of Stevan Lerner, who’d been one of the directors of photography on Terrence Malick’s Badlands (1973); the golf course, here, looks like a lonesome prairie. In one of Chevy Chase’s many ad-libbed, drunken-master-ish non sequiturs, Webb responds with a question of his own: “You take drugs, Danny?” “Every day.” “Good. So what’s the problem?”

Webb is not so much a mentor, we’re immediately led to understand, as he is an anti-mentor; like John C. McGinley’s Dr. Cox to Zach Braff’s J.D. on Scrubs, say, Webb rejects the notion that anyone can get to where they belong in life by following someone else’s advice or example. In a cruel-to-be-kind effort to prevent the young seeker from perceiving him as a mentor figure, he even calls Danny “Betty.” (Cf. Dr. Cox’s many girl’s names for J.D.) Our romantic dreamer isn’t about to embark on a Hero’s Journey, guided by a fairy godmother or a wise sage. Caddyshack teases us with the prospect that this is going to be a Dick Whittington folk tale, in which the virtuous young man’s every dream comes true — but it will not.

When Noonan wins the caddy’s tournament, he doesn’t walk away from that triumph with the world-weary irony of a hustler too cool to celebrate. Instead, he heads to the dormitory where Bushwood’s exchange students live, and gratefully receives their applause. The snaggle-toothed grin plastered across his mug at 42:08 is a beaming smile that we rarely see from him. He’s come to take Maggie for a swim; she takes him to her bedroom instead. This is a false ending to the movie: Our hero has won the contest, but has remained true to his roots. He’s uncorrupted by his brown-nosing. However, the movie’s not over yet. Noonan’s greatest test lies ahead.

When Lacey Underall rescues Noonan from Chuck Schick’s micro-aggression, she has an ulterior motive. The bored socialite wants to dally with the kid from the wrong side of the tracks. She seduces Noonan all too easily — because he’s still caught up in his Cinderella fantasy about being swept away from his life of poverty and toil, into a life of luxury and ease. When Smail’s niece — the closest thing this movie has to a princess — suggestively licks his palm and takes him back to the Smails’ house, Noonan seems to think that his fantasies are being made manifest at last.

There’s a visual gauziness to the erotic montage, a dreaminess to the instrumental/wordless vocal music, in the Danny/Lacey bedroom scene (58:33 – 59:05) that hearkens back to the bicycling scene in which we saw Noonan gaze longingly at the mansions near Bushwood. Although this is really happening, Noonan can’t quite believe it; he’s living out a fantasy. He’s been whisked away from his normal life into Judge Smails’s own home; he’s making love to Smails’s niece in Smails’s bed; he dons Smails’s robe. As Fig. 5 indicates, what’s transpiring here is the opposite of the ideology expressed by Ladder Climber complex. Noonan didn’t put in the work, jump through the hoops, elbow his way to the top. He was transported there, as though by magic. Work, as he’d half-suspected all along, is for suckers.

This idyll soon turns into a nightmare, of course. Adam and Eve’s sportive play is interrupted by a vengeful God, who drives them from paradise. We’ll get back to this entertaining sequence when we discuss the paradigm Judge Smails. Instead, let’s skip ahead to the moment when — after a cringing Noonan shakes Smails’s hand and agrees to be his creature — Noonan is picked by Ty Webb to be his caddy for the money match. He can’t bring himself to admit to Webb that he’s now Smails’s accomplice; instead, he wordlessly directs Ty to the care of the grinning Motormouth (1:21:27). Noonan’s romantic dream, it turns out, doesn’t feel so good. He has embarked on the road to becoming a Beeper, but wishes he hadn’t.

As the money match progresses, Noonan looks the other way when Smails cheats (1:22:43). Conscience-stricken, however, he eventually confesses to Ty that Smails is cheating (1:25:43), but — as ever — his anti-anti-mentor won’t let him off the hook so easily. “Nobody likes a tattle-tale, Danny. Except, of course, me.” As always, Webb’s wisdom is self-contradictory.

In fact, Webb — who is psychologically fragile, who doesn’t have his own shit figured out — begins to lose it, as the money match progresses. Once Noonan joins Webb’s team, the zen prepster who doesn’t play against other golfers becomes obsessed with winning. “See your future. Be your future,” he says, one of the movie’s oft-quoted lines. “Make, make, make it.” He’s reduced to stammering self-actualization platitudes. We’ll analyze this moment again, later in the series. The point is: Noonan is truly on his own, from here on out. He must, in this moment, listen to his own heart beatin’.

One final note about the Romantic Dreamer thematic complex. As Fig. 5 indicates, Romantic Dreamer is adjacent to one of the top-right vertex’s two paradigms; that is, it offers a clue about this paradigm. As we can see, the UNWORK paradigm’s complexes progress from Disgruntled Laborer to Savvy Hustler to Romantic Dreamer, i.e., from pragmatic-accepting through pragmatic-cynical to idealistic. What’s beyond idealistic, when it comes to unwork? When our analysis brings us to the complex adjacent to Romantic Dreamer, we’ll find out.

There you have it: the other half of Dr. Beeper vs. Danny Noonan, our Caddyshack meaning map’s second code. I’ve identified the paradigm Danny Noonan’s contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes, and brought these to life via a selection of source codes (“signs”) drawn from the movie. I’ve established not only what Noonan means — that is, what sense we Caddyshack viewers are encouraged to make of the character — but how Noonan means what he means. To that end, I’ve surfaced many of the visual and verbal cues, from speech acts to facial expressions, clothing, mannerisms, etc., via which we are encouraged to construe what Danny Noonan signifies not only within the movie, but also as an emblem of, you know, American Culture and Western Civilization c. 1980.

This series’ next installment will look at one-half (that is, one of two paradigms) of the third Caddyshack code: Judge Smails vs. Carl Spackler.

Click here for the Judge Smails post.