Golf Club

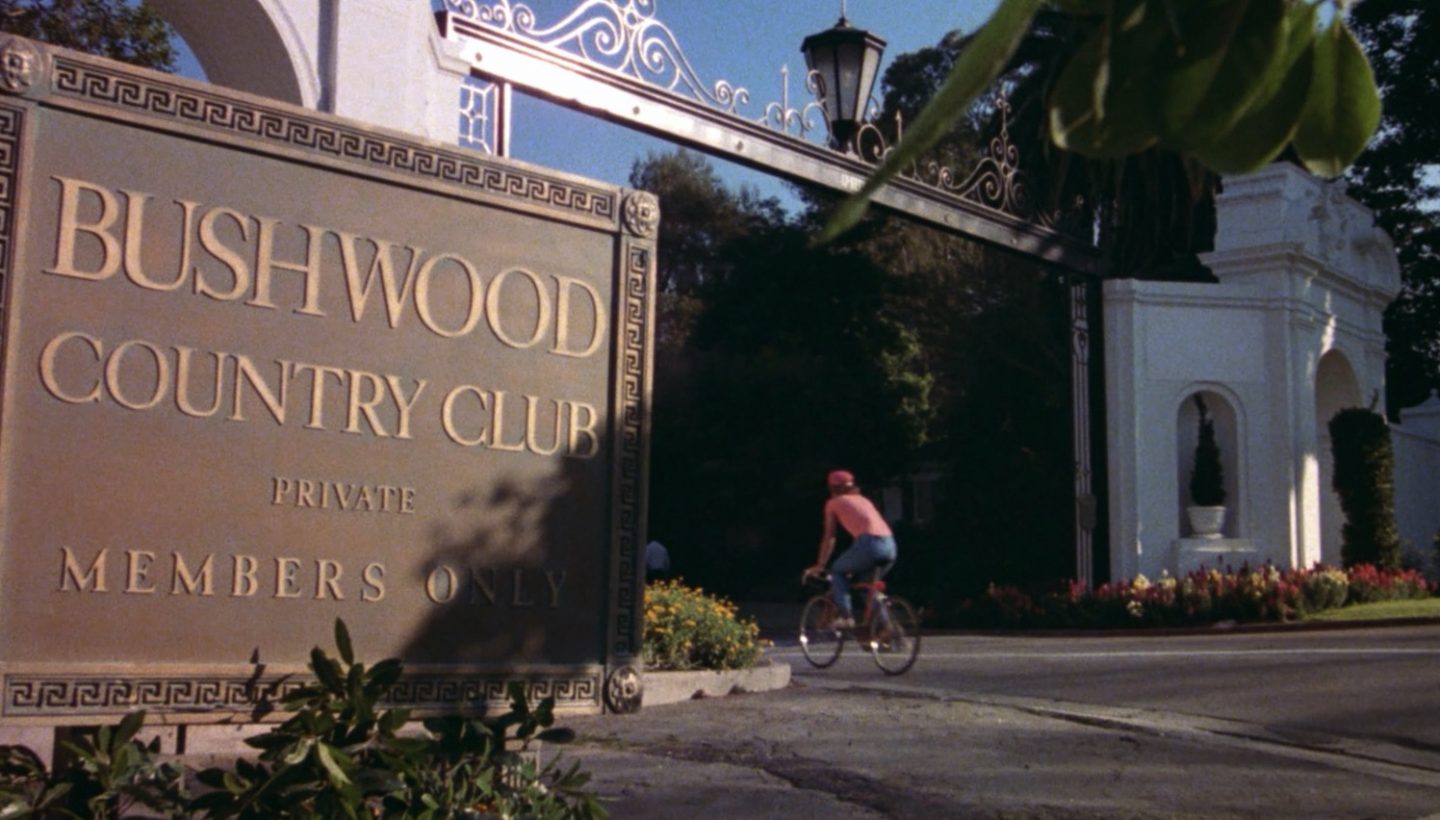

Danny Noonan enters the Bushwood Country Club (4:07)

This is the second installment in a series of posts offering a semiotic analysis of the 1980 golfing comedy Caddyshack. (Why select this particular, not very successful, deeply flawed movie? See the series introduction.)

According to my own analytical methodology, which I’ve fine-tuned while fossicking as a consulting semiotician for the past 20+ years, the lineaments of any semiosphere — whether a product or service category, that is to say, or a cultural territory, or a complex cultural production such as a novel, movie, or pop-culture franchise — can most usefully be diagrammed via eight unique paradigms. These paradigms, once thoughtfully juxtaposed vis-à-vis one another, i.e., in a fashion that ensures maximum “meaning-tensegrity,” if you will, serve us as the vertices of not one but two semiotic squares.

When the second of these squares is rotated 45 degrees and overlaid upon the first, the resulting shape is a regular octagrammic star figure. By superimposing upon this eight-pointed figure a circle divided into four quadrants, each of which is further divided into four pie-slice segments, over time I’ve developed the “G-Schema” — an accessible diagram that is nevertheless sufficiently complex to illuminate what Max Weber (in Clifford Geertz’s paraphrase) described as the “webs of significance” that we humans spin, only to find ourselves suspended in them. The G-Schema is named after Gadamer, Greimas, and Geertz, three theorists who helped inspire its development; it’s also named after yours truly. PS: If the moniker should put you in mind of Lacan’s 1954 “L-Schema,” that’s very much on purpose.

If culture is a Laser Hallway of sorts, then think of the G-Schema as a cat burglar’s aerosol mist, i.e., a heuristic that was purpose-built to render visible an otherwise baffling semiosphere’s invisible web or network of meaningfulness.

☸

The embryonic diagram shown below reveals what SEMIOVOX’s Caddyshack G-Schema looked like on the first day of mapping. At that point, I had barely begun to limn the first of our two semiotic squares, i.e., by naming the two paradigms (Golf Club, Caddy Shack) that I understand to constitute the schema’s “master code.” I had already surfaced and dimensionalized the source codes (“signs”) at play in these two paradigms’ four (total) thematic complexes, but I hadn’t yet named the complexes. Nor had I yet named the schema’s four quadrants. Although I won’t attempt to account for each step in the often frustrating, upward-spiraling hermeneutic process via which I identify and evolve each G-Schema’s various elements, in an effort to demonstrate SEMIOVOX’s approach to meaning-mapping I’ll update the Caddyshack G-Schema as we go along.

I’ve named my idiosyncratic method of meaning-mapping the “G-Schema” after my intellectual heroes, the hermeneut Hans-Georg Gadamer, the ethnographer Clifford Geertz, and the comparative mythologist A.J. Greimas. Their theorizing and practices — particularly Geertz’s, which is ironic since he abhorred structuralist diagramming — has informed my own thinking about how most advantageously to map meaning. In addition, the G-Schema, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects (i.e., what phenomena mean), described by their virtuality (i.e., within the context of a particular semiosphere), to their lineaments (i.e., how phenomena mean what they mean), is immodestly named after yours truly.

As I’ve previously noted in this publication’s Real Food Audit series, as well as in our Coronavirus Codes series, each of a G-Schema’s paradigms is paired off with an opposing paradigm, resulting in four codes — each of which thus assumes the form of a binary opposition. (In his helpful description of binary semiotic codes, Geertz speaks of “values and disvalues”; elsewhere, he describes a code as a combination of a “symbolic expression” and its own “direct inversion” — which is the same idea.) Going forward, therefore, each of the initial eight installments in the current Caddyshack Codes series will be devoted to unpacking a single paradigm — one-half of one of our Caddyshack schema’s four codes — via an analysis of that particular paradigm’s two contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes. We’ll then conclude by revisiting the full schema syncretically.

Enough preamble! The second installment in this series begins now.

Paradigm

We’ll begin, as a semiotician should always begin his or her project debrief, with what I’ve determined to be this semiosphere’s structural matrix or “master code” — i.e., the symbolic expression of its dominant discourse. It should come as no surprise to anyone who’s seen the movie, or merely learned its title, that the Caddyshack master code is Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack. In this installment, we’ll focus on one-half of this code: Golf Club.

Adapting the terminology of C.S. Peirce’s existential graphs — a c. 1903 diagrammatic system to represent “the fundamental operations of reasoning” — we’d describe the Golf Club categorical proposition like so: “It is not the case that there exists a Caddy Shack that is not Golf Club.” The Caddy Shack’s ideas, values, and so forth are assumed to be those of the Golf Club.

According to SEMIOVOX’s analysis, the paradigm Golf Club is constituted by two contrasting but not entirely contradictory thematic complexes that I’ve tentatively titled — through a hermeneutic process that, as always, involved a lot of crossings-out and crumplings-up, as I tested and rejected one G-Schema hypothesis after another — Virtuous Insider and Time Killer.

Virtuous Insider

The first shot in Caddyshack reveals to us the Bushwood Country Club golf course, early in the morning. Sprinklers play like the fountains at Versailles; ethereal music can be heard on the soundtrack. We are in a rarefied space, shut off from and immune to the hustle and bustle of the outside world. There’s a similar moment, later (53:02), when we first see the Rolling Lakes Yacht Club; although bustling with activity, it’s an oasis of order and peace. In SEMIOVOX’s schemata, each of a master code’s paradigms straddles two map quadrants; this thematic complex is within the ORDER quadrant.

Throughout the movie, we are led to understand that — according to the self-serving weltanschauung of its members — Bushwood offers material, incontrovertible evidence of the usefulness of virtue. Bushwood’s echt-WASP denizens believe that they’ve earned access to this sort of privilege thanks to their (or their ancestors’) hard work, self-denial, and goodness. When the stentorian Judge Smails (Ted Knight) barks at his lazy, greedy grandson, Spaulding (John F. Barmon Jr.), who’s eager to pig out at the course’s snack shack, that “You’ll get nothing — and like it!” (26:04), we’re seeing a punitive version of the Weberian spirit of capitalism dramatized. Smails finds himself compelled to police Spaulding’s un-WASPy inclinations, which threaten his own faith in his family’s God-given wealth and status. This also happens to be a hilarious line reading, one of Knight’s very best.

The sense that one must earn access to Bushwood (as well as Rolling Lakes), i.e., not merely by ponying up membership fees but through public demonstrations of one’s WASPy virtues, is all-pervasive. Catholic caddies like Danny Noonan and Tony D’Annunzio, the Irish exchange student and waitress Maggie O’Hooligan, the African American shoeshine man Smoke Porterhouse, and the nouveau-riche builder Al Czervik will never cut the mustard. Douglas Kenney, who cowrote Caddyshack with Brian Doyle-Murray and Harold Ramis, was outraged by this sort of thing.

Himself the son of a country club tennis pro, Kenney cofounded National Lampoon in 1970 and co-wrote 1978’s Animal House, via which popular vehicles he ruthlessly satirized WASP culture. In Chris Nashawaty’s 2018 book Caddyshack: The Making of a Hollywood Cinderella Story, we read that that “[Kenney] and Doyle-Murray both knew, deeply, the smoldering resentment, insecurity, and jealousy of growing up and feeling excluded….” Via their movie, Kenney, et al., are eager for us to understand that WASPdom’s self-congratulatory culture is flaccid, hypocritical, and corrupt.

Early in the movie, when Judge Smails, Dr. Beeper, and The Bishop are golfing together, the caddies roll their eyes when these pompous asses bullshit about their scores. (26:37) Why do they BS? Being a good golfer, for these pillars of society, has become yet another sign of their virtue, their earned access to the paradise on Earth which is Bushwood. So they cheat, and lie. While persuading themselves, somehow (e.g., “Winter Rules”), that their behavior is perfectly legitimate. This is why Judge Smails, who at some level doesn’t believe his own malarkey, tends to crack under pressure. When a crowd gathers to watch him drive off the tee, Czervik having jokingly announced that Smails will slice his shot, he glares in rage and terror; Knight here gives one of the simpering laughs for which his Mary Tyler Moore Show character Ted Baxter was infamous. (27:00) His poor sportsmanship will lead to a near disaster… which Noonan will seize on as an opportunity to ingratiate himself… but we’ll get to that later.

The Bushwood scene is one of stultifying calmness, inhibition, and uptightness. The self-congratulatory notion that everyone here deserves their privilege fatally inhibits spontaneity, free expression, truth-telling, and wit. It’s no longer the 1950s, but you wouldn’t know it from the Country Club’s sclerotic Fourth of July gala. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living, here. (The spontaneous, freely expressive, truth-telling, witty Al Czervik will liken the club’s partygoers to zombies, but we’ll get to that in a later post.) The music, the dancing, the outfits, even the women’s dated hairdos serve as an implicit rebuke to the outside world’s ever-evolving norms and forms. When Smails brags about his uniform to his niece, Lacey (30:14), for example, she can’t be bothered to feign interest; she, too, it will transpire, is a threat to Bushwood’s order.

At a formal level, the earned-access ideology is put across via precisely this atmosphere of ease and tranquility. No flop sweat is allowed. It’s important that the club’s members appear to have risen to their positions in society through hard work which is also somehow effortless — because this smooth sailing suggests a wind at one’s back, an ordained and inevitable success. As we’ll see when we analyze the Caddy Shack aspect of the Golf club vs. Caddy Shack code, the non-WASP outsiders are sweaty, greasy, stained, awkward. They don’t know how to dress, speak, or behave properly; they’re rebuked constantly — for no reason other than to remind the club members of their own special status. In fact, it’s a telling sign of Smails’s fall from grace (if you will) when, during the climactic golf game, he breaks into a flop sweat. Semioticians talk about “marked” and “unmarked” terms, and here these descriptors become literal: If frizzy hair, armpit stains, and Bushwood t-shirts mark the club’s lumpenproles, then their absence is also a signifier.

PS: A semiosphere’s “unmarked” term (in this case, the Country Club) is the default, the norm — that which the semiosphere asks you to take for granted. It’s also known as the “minimum-effort” term, since it’s seeming naturalness and inevitability renders it unremarkable…. Minimum effort is projected by Bushwood’s denizens, in strong contrast with the sweaty, Sisyphean labors of the caddies.

The movie’s depiction of the most zombified — shuffling, muttering, thoroughly out-of-it — Bushwood members is unexpectedly delightful. Kenneth and Rebecca Burritt as Mr. and Mrs. Havercamp, who blithely drive their golf balls into water traps, and don’t so much as blink an eye when a tea service comes crashing down at their feet (11:55–12:45, 1:00:53), are a hoot. Although we laugh at them, we’re not asked to find these folks repulsive; theirs has evidently been a satisfying, if blinkered and privileged life. What we’re asked to question is the premature old fogie-ness — the reflexive self-zombification — of the club’s middle-aged members.

From Smails and his wife to hired flunkies such as the groundskeeper McFiddish (Thomas Carlin), caddy shack honcho Lou Loomis (Brian Doyle-Murray, one of the movie’s creators), and the lifeguard (Marcus Breece), Bushwood and Rolling Lakes are replete with enforcers of the status quo. But the status quo’s most effective enforcer is an ideology — which we’ve begun to get a sense of, in the notes above — that everyone is encouraged, via subtle and not so subtle means, to internalize and accept as natural. When it comes to ideology, the “uncanny valley” effect is always in play: The more natural, eternal, and inevitable the ideology is made to seem, the creepier; and conversely, the more awkward and artificial the ideology is made to seem, the more we can — in a way — find it charming. This helps us to understand the Stepford Wives-esque creepiness of Dr. Beeper and the Bishop (before his reverse Road to Damascus moment); and it is particularly useful in helping us comprehend the perverse charm of Judge Smails, whom Ted Knight brilliantly portrays as a man incapable of fully internalizing the dominant discourse that he champions — and endlessly driven, therefore, from one disorder of his own making to the next.

At its most effective and creepiest, ideology persuades without ever letting us realize that we’ve been persuaded. In Caddyshack, ideologues like Dr. Beeper and the Bishop are self-hypnotized; they are utterly self-confident. (See the Bishop’s golf game in a torrential storm [1:03:36]: “The Good Lord would never interrupt the best game of my life.”) Judge Smails, however, is apparently in some fashion unpersuaded that he in fact does deserve his position of status in society; and he is therefore entirely unpersuasive when he attempts to indoctrinate others into Bushwood’s earned-access ideology. When Noonan helps Smails out of a jam (28:10), Smails’s furtive, yet simultaneously authoritative behavior, signals loud and clear that one doesn’t necessarily have to earn access to the club (and privilege, generally); one can cheat one’s way in, too. If one knows how to play the game, etc., etc.

Kenney, et al., delight in spectacles of comeuppance. (When you read that word, please hear Orson Welles saying it in The Magnificent Ambersons.) Viewed through the lens of the Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack code, Caddyshack, like Animal House, is revealed to be a Lehrstück — a didactic “learning-play.” (Through the lens of the other codes, it’s also other sorts of movies.) The Bishop, played by Henry Wilcoxon, a leading man in many of Cecil B. DeMille’s films, and the pharaoh’s captain of the guards in DeMille’s 1956 remake of The Ten Commandments, will be struck by lightning (1:04:11) to the ironic accompaniment of music from The Ten Commandments. Dr. Beeper will sit in a pool of Spaulding’s vomit, and be nearly electrocuted by his own beeper. Poor Judge Smails, meanwhile, will undergo multiple humiliations and symbolic castrations. But more on these moments later. The point is, from the filmmakers’ perspective, the notion of “earned access” to social status, economic privilege, and cultural capital is a shibboleth.

Like Donald Trump, somehow president of the United States as I write these words, Smails and his cronies ascribe their own manifold sins to others. For a particularly egregious example, see the dustup in the club’s billiards room (1:10:36), when Smails chokes Czervik, then says, “He tried to choke me!” This sort of projection is one stratagem via which the dominant discourse goes unchallenged. A far more efficient and effective stratagem, however, is: scoffing. Perhaps the dominant discourse’s most powerful rhetorical weapon is a manipulative performance of wry incredulity: eye-rolling, tittering, a thrill of laughter in one’s speaking voice. If ideology seeks to persuade us that the way things are is the only possible way they could be, that another world is not possible, then scoffing at challenges to the discourse — rather than engaging the challenges directly — gets the point across. In the image above (1:12:04), Dr. Beeper (Dan Resin) reacts to Czervik’s golf-game challenge with exactly this sort of bemused jocularity.

I could go on about the Virtuous Insider theme, but the source codes (“signs”) described above will suffice. Let’s turn now to the paradigm Golf Club’s other, contrasting yet complementary thematic complex.

Time Killer

As noted earlier in this post, in any of SEMIOVOX’s G-Schemata, each of a master code’s paradigms straddles two map quadrants. While Virtuous Insider falls within the ORDER quadrant, the Time Killer thematic complex falls within the WORK quadrant. We now leave Max Weber’s area of expertise and enter Thorstein Veblen’s.

In his 1899 economic treatise The Theory of the Leisure Class, Veblen offered a corrective to neoclassical economics, in which people are depicted as rational agents who seek utility and maximal pleasure from their economic activities. In fact, he notes, wealthy people pursue social status and prestige via economically unproductive — and therefore irrational — practices of conspicuous consumption and conspicuous leisure. Such activities, argues Veblen, serves to validate the non-productive behavior of society’s resource-controlling members… by beguiling the lower classes into admiring rather than reviling their parasitic, useless existence. We’ll get to conspicuous consumption when I discuss Al Czervik, in a future post. Here, we’ll look at how Bushwood is a vector for conspicuous leisure — that is, killing time.

Bushwood is a place where the monied elite gather in order to do… nothing. In a scene that begins around 15:58, we find Dr. Beeper on the phone to the hospital, telling someone, “Just snake a tube down her nose, and I’ll be there in four or five hours.” Behind him, Drew Scott (Brian McConnachie, one of the main writers for National Lampoon and then Saturday Night Live), and Gatsby (Scott Powell, a founding member of Sha Na Na, and an orthopedic surgeon) studiously play a card game which turns out to be… Go Fish. Through this tableau, at the beginning of the scene, parades a triumvirate of old men draped in toga-like toweling; I’ve written about them elsewhere. Smails, whom as we will see is a paradigmatic figure of Order, enters (16:15) and testily demands, of the card players, “Don’t you have homes?” This is another of Knight’s perfect, unforgettable line deliveries — and this moment early in the movie signals that the paradigm Golf Club is an internally conflicted one; there’s an internecine conflict raging, here.

Note that Smails doesn’t object to Dr. Beeper’s weekend-warrior behavior — prioritizing his golf game over a patient in distress. As a self-appointed guardian of WASP virtuousness, Smails attempts to draw a bright line between acceptable, “earned” conspicuous leisure (e.g., golfing, yachting, skiing) and unacceptable leisure-class pursuits such as overindulging in drink, extramarital sex, smoking marijuana, or simply sitting around doing nothing — all of which go on under his nose, at various points in the movie. Smail’s niece, Lacey Underall (Cindy Morgan), is an avatar of such unacceptable leisure-class pursuits. When she meets Ty Webb (34:47), in a misguided effort to impress him, she brags, “I enjoy skinny skiing, going to bullfights on acid.” Her expert dive into the pool (45:21, performed by a not very persuasive stunt double), and the aplomb with which she does tequila shots (50:43) provides further evidence of a misspent life of time-killing.

Smail’s grandson Spaulding, too, is shaping up to be the wrong sort of WASP — that is, from Smails’s perspective. He’s spoiled, whiny, childish, and stupid. At the club pool, he’s the only one wearing a mask and snorkel — presumably, to ogle girls’ bottoms underwater. He drinks and smokes weed, but in the least sophisticated way possible. At the July 4th gala, he sneaks discarded half-full glasses of wine, whiskey, and other drinks (35:24); and after accidentally drinking someone’s cigarette ashes, he vomits through the sunroof of Dr. Beeper’s waiting car (35:56). And when he brags, about his apparently shitty weed (53:19), that “It’s the best, man. I got it from a Negro,” the implication is that he’s not only racist but an easy mark. Spaulding is to Caddyshack what Stephen Furst’s Flounder was to Animal House: a privileged legacy kid who can’t hold his liquor, and certainly doesn’t deserve his status; he’s fated to go through life “fat, drunk, and stupid.” However, whereas Flounder was sweet-natured, Spaulding is an asshole; witness his “Ahoy, polloi” moment with Noonan at 54:10.

Speaking of Noonan, when the movie begins he sees only two options: Join the leisure class (by scheming his way into a college scholarship, and eventually going to law or medical school, or into finance, etc.), thereby becoming an elitist time-killing wastrel like the golfers for whom he caddies each summer; or go to work at the lumber yard with his industrious father. As we’ll see when we examine the paradigm Caddy Shack (in this series’ next installment), the life of the industrious worker is one of toil and scarcity, one is forced to kowtow to out-of-it snobs, and one’s free will is repressed by a value system maintained by one’s hypocritical oppressors.

In his introductory essay for The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011), the second in a trilogy of books we’ve created together [1], University of Toronto philosopher Mark Kingwell notes the following about what he calls the “work idea.”

Work deploys a network of techniques and effects that make it seem inevitable and, where possible, pleasurable. […] In effect, work is the largest self-regulation system the universe has so far manufactured, subjecting each of us to a generalized panopticon shadow under which we dare not do anything but work, or at least seem to be working, lest we fall prey to an obscure disapproval all the more powerful for being so.

When it comes to the ideology of work — the subject of this section of the current installment in this series — the Golf Club offers us the spectacle of hard-working proles being chastised as lazy, disobedient, and ill-behaved by members of a leisure class whose own behavior is odious. Which is, of course, why Kenney, Doyle-Murray, and Ramis set the movie at the fictional Bushwood.

So there you have it: one-half of Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack, our Caddyshack meaning map’s master code. In this post, I’ve identified the paradigm Golf Club’s two contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes, and brought these to life via a selection of source codes (“signs”) drawn from the movie. In doing so, I’ve established not only what the golf club means — that is, what sense we Caddyshack viewers are encouraged to make of this golf club scene — but how the golf club means what it means. To that end, I’ve surfaced many of the visual and verbal cues, from speech acts and tonality to facial expressions, clothing, body language, etc., via which we are encouraged to construe what the golf club signifies not only within the movie, but also as an emblem of, you know, American Culture and Western Civilization c. 1980.

The series’ next installment will take a close look at the thematic complexes and source codes of Caddy Shack — i.e., this paradigm’s opposite number, and the avatar of Caddyshack’s anti-Golf Club counter-discourse.

Click here for the Caddy Shack post.