A version of this essay appeared in the “Thing” column of the journal Cabinet (Summer 2006).

Forget The Da Vinci Code, that ham-fisted compendium of half-baked claptrap. You want psychedelic revelations about the artificial nature of reality? Want ringside seats for the never-ending battle between radical change agents and the forces of epistemological orthodoxy? Look no further than the 1968 animated movie Yellow Submarine, an Argonautica-meets-Alice in Wonderland fantasy in which the Beatles voyage across space and time to free a utopian Pepperland from the Albigensian Crusade-style depredations of the Blue Meanies.

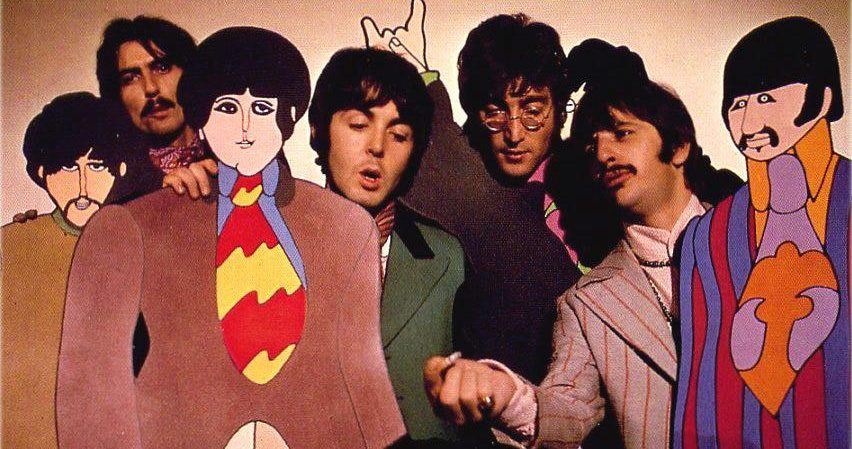

Need proof that the quest for gnosis is a threat to established institutions? Look no further than the object pictured here, in all its obscene materiality.

Directed by George Dunning and art-directed by Heinz Edelmann without any input from the Beatles themselves, Yellow Submarine was an exercise in misprision, i.e., a creative misreading of an influential text — in this case the 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The film’s effort to construct a meaningful narrative from “A Day in the Life,” “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” and the record’s title track was every bit as paranoid, really, as Charles Manson’s simultaneous effort to do the same with the Beatles’ so-called White Album.

But Yellow Submarine was also paranoid in the they’re-out-to-get-us sense… because the film portrays the powers-that-be as always looking to crush gnosticism.

How, exactly, is Yellow Submarine a gnostic movie? It’s obvious once you know what to look for. The gnostic attempt to achieve intuitive knowledge of the infinite is enacted by the yellow submarine’s voyage out of the material world into Nowhere Land. Also, the gnostic desire to be united with one’s higher self is articulated by the “John” figure, who, upon encountering the Lonely Hearts Club Band, sagely opines that they’re “extensions of our own personalities suspended, as it were, in time, frozen in space.” And the religio-political establishment’s determination to be humanity’s sole conduit to divine wisdom? It’s expressed by the Chief Meanie’s dictum: “Let us not forget that heaven is blue… tomorrow the world!”

As for the object in question, it’s an extremely rare Yellow Submarine merchandising tie-in, a weapon referred to but never actually pictured in the movie: not the Meanies’ Anti-Music Missile or the Dreadful Flying Glove but the O-blue-terator. It was doubtlessly conceived and produced by the pop-culture arm of the anti-gnostic institutional complex to which I have already alluded. It’s obscene not merely because it’s an epistemological WMD for kids, but because Yellow Submarine cannot and should not be three-dimensionalized.

Speaking of which, audiences at the time were shocked by Edelmann’s employment of limited animation, an inexpensive alternative to Disney-style cartoon realism in which cels and sequences of cels are animated on top of static cels. Compared with a multidimensional, hand-painted Disney cartoon, say, Yellow Submarine did look flat and crappy. Yet limited animation is what Marshall McLuhan called a cool medium: Its low definition of information requires viewers to participate actively in the creation of meaning. Given the movie’s gnostic message, this medium is only appropriate. “John,” “Paul,” “George,” and “Ringo,” not to mention the Nowhere Man, the Chief Meanie, and the movie’s other figures, aren’t characters but symbols. And — as we’ve been instructed most recently by the paintings of Laylah Ali — in order to engage the imagination, symbols must remain flat abstractions. ALSO: Disney was, in those days, the most middlebrow (and therefore anti-gnostic) thing going; note that the Blue Meanie shock troops wore Mickey Mouse ears!

“You surprise me, Ringo,” says “John” at one point in the film. “Dealing in abstracts.” The Blue Meanies, of course, want to make surprise impossible; their vision of utopia is a postmodern-middlebrow one in which everything forever means one thing and one thing only — a fate worse than meaninglessness itself. This is what Herbert Marcuse (surely one of the primary inspirations for Yellow Submarine, along with the Symbolist movement) was getting at when he described the US and the USSR alike as “one-dimensional” social orders. The great insight of Dunning and Edelmann was that creative misreading, which is the hilobrow’s preferred mode of reading and interpreting, and a pretty good definition of gnosticism, is impossible unless the “real world” is first flattened out — into one-dimensional symbols pregnant with discoverable and inventable meaning.

Full speed ahead, Mr. Parker, full speed ahead!