Disney Co. Mascot

In a 1953 interview, Walt Disney would lament, “Mickey’s our problem child. He’s so much of an institution that we’re limited in what we can do with him. If we have Mickey kicking someone in the pants we get a million letters from mothers telling us we’re giving their kids the wrong ideas. Mickey must always be sweet, always lovable. What can you do with such a leading man?”

In a 1989 Journal of Popular Culture essay on “The Masks of Mickey Mouse,” Robert W. Brockway would answer Walt’s question:

During the mid-fifties, as the genial host of Disneyland in tails, Mickey… climbed to the top of the Disney corporate empire as the corporate image. This was his most recent metamorphosis. The middle-aged Mickey mirrors the world of the corporate executive. He became an ‘organization man.’ He also became the king of the Magic Kingdom and his appearances took on the mystique of monarchy.

It’s this 1954–1963 version of Mickey that we’ll see critiqued savagely in the Fifties and Sixties — cf. the next two installments in this series. (NB: Adorno’s prescient critique, noted in this series’ previous installment, anticipates The Fifties-Sixties M backlash.) But for the moment, let’s linger with MM the corporate icon.

The Fifties (1954–1963, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema) is known today as the Golden Age of television. In 1954, Walt Disney helped get things started by selling the company’s first TV show — Walt Disney’s Disneyland — to ABC. Disney used the show to unveil Disneyland. The theme park would open in Anaheim, California in 1955.

Beginning in 1955, ABC aired the massively popular variety show The Mickey Mouse Club. Mickey emerged from retirement as the show’s host. He showed up not only in vintage cartoons, but also in the show’s opening, interstitial, and closing segments.

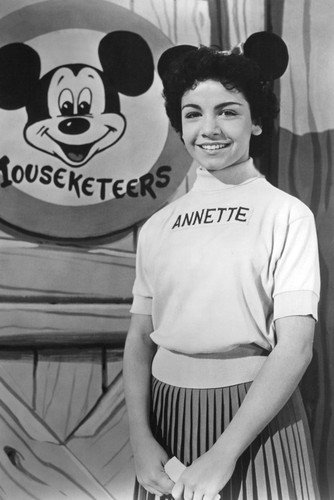

If he was bland before, now Mickey became squeaky-clean — an avuncular stand-in for Walt himself. The main cast members of the The Mickey Mouse Club — including Bobby Burgess, Lonnie Burr, Tommy Cole, Annette Funicello, and Darlene Gillespie — constituted a wholesome cult: They wore Mickey/Minnie ears, and sang a paean of praise to the Mouse in each episode. They were known as the Mouseketeers.

In a 1999 essay in the journal Visual Resources, Barbara J. Coleman explains The Mickey Mouse Club like so: “During a time of economic abundance and Cold War vigilance, it taught group lessons about consumerism, appropriate social behavior, and good citizenship.”

Mickey was everywhere represented at Disneyland — which opened in Anaheim, California in 1955. Here, too, Mickey represented Walt himself. Mickey’s visage appeared everywhere — explicitly and subliminally. A constumed Mickey greeted visitors at the gate. Mickey was now Disney Co.’s official mascot — an avatar of The Walt Disney Company.

During the Fifties, Mickey was simultaneously expanded and flattened out. As The Walt Disney Company’s mascot and logo, he was ubiquitous; but he no longer represented anything other than “wholesome family fun.” He no longer appeared as a character in movies; he was a corporate cheerleader.

According a precedent set in 1979, a trademark can protect a character in the public domain as long as that character has obtained what is called “secondary meaning,” i.e., upon seeing the character, one will immediately identify it with a company/brand. Copyright lawyer Stephen Carlisle claims that Mickey Mouse meets this qualification: “Disney has made Mickey Mouse so prominent in all of their corporate dealings, that he is effectively the pre-eminent symbol of the Walt Disney Company. There can be little doubt that anyone seeing the image of Mickey Mouse (or even his silhouette), immediately thinks of Disney.” That is to say, Disney has ingrained Mickey Mouse so deeply in its corporate identity that the character is afforded legal protection for eternity — because trademarks last indefinitely.

In a 2004 New York Times story, Jim Hardison — creative director of a company that revitalizes bygone cartoon characters — offered an explanation of why MM’s new status as the Disney Co. mascot would prove problematic for the character:

Disney says, “We are basically selling happiness.” But that requires a sort of ruthless efficiency that tends to undermine the whole fun-loving image they present. Over time, that shadow story has gained some traction with the audience, and as the symbol of what Disney stands for, Mickey can’t help but pick up a little bit of that shadow.

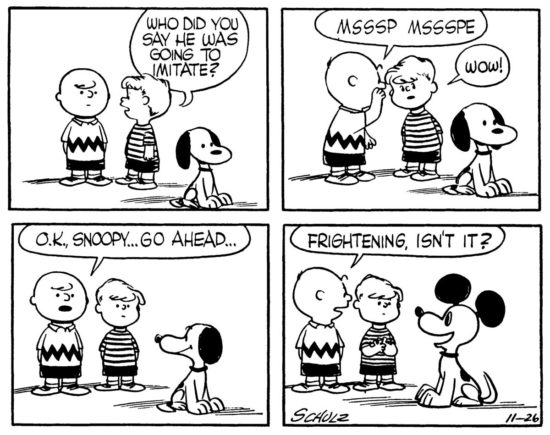

I’ve suggested elsewhere that statues of unelected leaders — let’s call them despots — are meaning-bearing sign vehicles whose purpose it is to elicit or provoke, at a preconscious level, a desire to see that statue toppled and beheaded. Mickey Mouse became exactly this sort of icon, beginning around 1954. As a result, the Mickey backlash went mainstream.

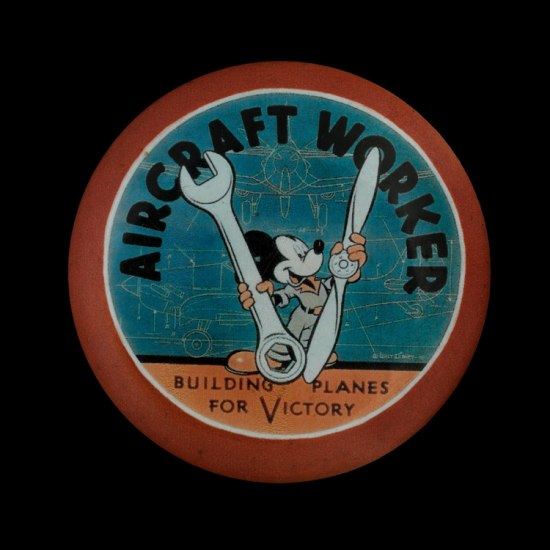

Mickey’s wartime role as an emblem of the United States itself contributed to the backlash, too. Throughout the war, Disney cranked out military training films, educational shorts, and military insignia for over 1,000 different units in the U.S. armed forces. Disney’s stable of characters was employed in the name of patriotism; up to 90 percent of the Disney studio’s work, c. 1943, was for government agencies.

Disney characters appeared on posters, in books, and on war bonds to boost their appeal to children. “The Studio’s work was not just instrumental in the United States’ war effort,” we read in an essay on “Mickey Mouse morale” at the National Museum of American History’s website. “Using Disney characters to speak on behalf of the U.S. government also solidified the idea—building since Disney’s 1930s cartoon work — that the brand was associated with patriotism and a symbol for America writ large.”

Precisely because Mickey had become a symbol of America’s inherent innocence, goodness, and can-do optimism, artists and activists with a more skeptical view of America would seize upon Mickey as a handy symbol, the subversion of which had a certain amount of guaranteed shock value.

The beginning of decolonization took place in the Fifties; a kind of psychic decolonization was also happening within America itself. Mickey — perceived as a cheerleader for capitalism and America’s global cultural hegemony — would now become the target of subcultural freedom fighters.