Forties Backlash

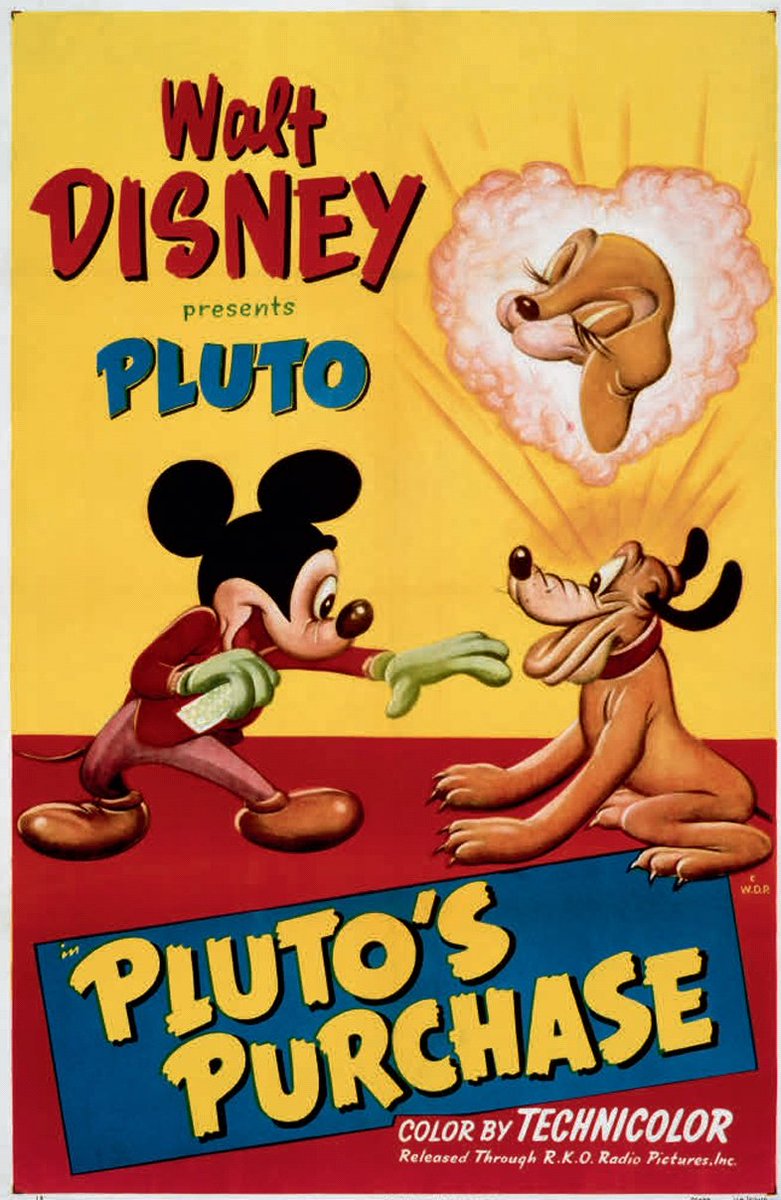

Walt Disney unveils the Mickey Mouse gas mask

“The creature who gave his name as a [1950s-era] synonym for insipidity had a gutsier youth,” Stephen Jay Gould would complain in the 1970s, about Mickey’s evolution. The Frankfurt School theorists T.W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer were on the case long before that; and their critique is much more far-reaching.

“The misplaced love of the common people for the wrong which is done them is a greater force than the cunning of the authorities,” Adorno and Horkheimer write in their Dialektik der Aufklärung (Dialectic of Enlightenment), circulated in samizdat form among friends and colleagues in 1944. “It calls for Mickey Rooney in preference to the tragic Garbo, for Donald Duck instead of Betty Boop. … The conformism of the buyers and the effrontery of the producers who supply them prevail. The result is a constant reproduction of the same thing.”

Mickey Rooney and Donald Duck (Mickey Mouse is the unspoken third point of this triangle) represent the bland, inoffensive, churned-out product of the factory-like Culture Industry, while Greta Garbo and Betty Boop represent truly popular culture: weird, alluring, eccentric, original and incommensurable. Already, at the very beginning of the Forties (1944–1953, according to HILOBROW’s periodization), Adorno and Horkheimer are lamenting that — to quote David Bowie — Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow.

Dialectic of Enlightenment consists of several essays tracing the origins of totalitarianism ; it’s an effort to grok the triumph of Nazism in Germany, and to warn America — Adorno and Horkheimer’s adopted homeland — about how it might happen here. The essay titled “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” in which the Donald Duck/Betty Boop line appears, is generally credited to Adorno alone. Indeed, during the Forties Adorno wrote several penetrating essays on the “culture industry” — a term he used pointedly, because he insisted that “popular culture” in the United States isn’t truly popular; it’s the organized manipulation of consumer preferences.

Adorno is frequently dismissed — by folks across the political spectrum — as a mandarin, i.e., an elitist who hates pop culture. In fact, he applauded unique and eccentric lowbrow productions, from circuses to peepshows — which he described as being every bit as “embarrassing” to the coercive aims of the American culture industry as are those highbrow works (e.g., Schoenberg) for which he is a better-known advocate. As we can see from the passage quoted above, he’s not anti-cartoon. Adorno digs Betty Boop — Max Fleischer’s anthropomorphic French poodle and sex symbol — who was hailed as the “queen of the animated screen” from 1930–1939. What he doesn’t dig is the calculated cuteness and pseudo-eccentricity of Disney’s characters — as they’d evolved from their weirder, gutsier, Boop-like origins due to market pressure. He’s right!

The American culture critic Dwight Macdonald, the sociologist David Riesman, and others would follow in Adorno’s footsteps — warning that middlebrow culture is bad for society. Middlebrow literature, movies, music, art, and other cultural productions constitute a persuasive but noxious advertisement for adjustment, obedience, passivity.

W.H. Auden, in a 1944 New York Times book review, agrees:

A comparison of “Grimm’s Fairy Tales” with our movies, radio serials, comic strips and slick magazines reveals that what today passes for popular art is not the creation of simple ‘lowbrow’ men and women (though the natural child of the folk-tale still lives, eking out a precarious, furtive existence in bars and on sidewalks or walls), but a degenerate “middlebrow” horror, mass-produced for profit by fully conscious, well-educated young men who read the classics in their spare time….

How to resist the allure of Middlebrow while still celebrating what we enjoy and admire about Mickey Mouse? From the Fifties onward, and continuing today, there have been a number of efforts — some more relevant and engaging than others — to answer this question, which in a way was first posed by Adorno.

Subsequent installments in this series will survey some of the more notable efforts of which I am aware.