The great unity

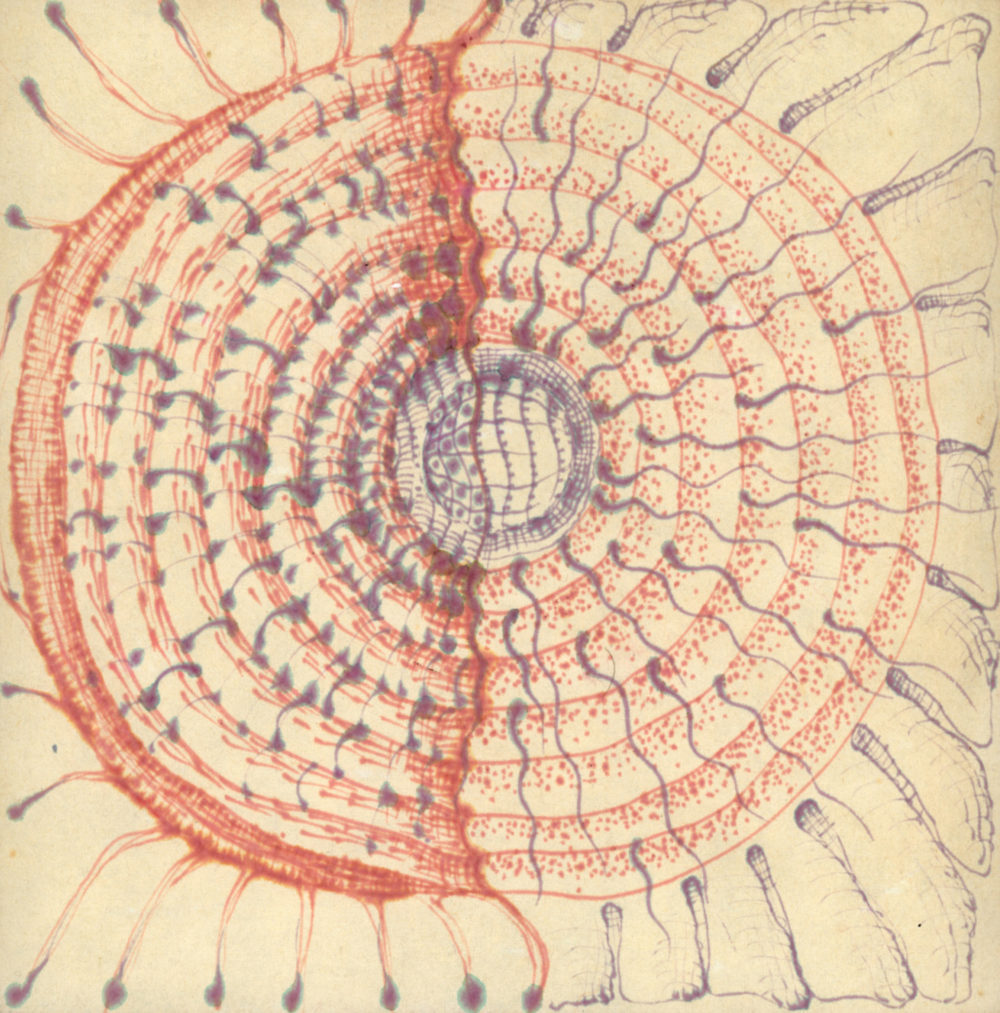

Jordan Belson's "Brain Drawing" (1952)

“We must try to achieve the fullest consciousness of our existence which is at home in the two unseparated realms,” writes Rilke to a translator of his Duino Elegies (w. 1912–1922, p. 1923), because our existence is “inexhaustibly nourished by both.” He adds: “There is neither a here nor a beyond but the great unity.”

Referencing this letter, Lawrence Durrell would remark, in his A Key to Modern British Poetry (1952), “This is not only good mysticism, it is a not entirely inadequate view of the kind of thing the relativity philosophers are talking about.”

Mysticism, modern poetry, Einstein’s theory of special relativity… all circling around a notion of the mutually constitutive identity of opposites within a given system. How to depict such a system? With “some of the humility of the modern scientist for whom there are no more ‘facts’ but simply ‘point-events’ strung out in reality,” suggests Durrell. In analyzing modern poetry, he confesses: “In reality we are simply making a rough-and-ready star-map of a universe which we do not perfectly understand.”

Which is a not entirely inadequate description of a G-schema.

PS: Jordan Belson (1926 – 2011) was an American artist and abstract cinematic filmmaker who created nonobjective, often spiritually oriented, abstract films. Much of his work, like the example here, is meant to evoke a mystical or meditative experience.

A selection from a series of posts — originally published by our sister website, HILOBROW — attempting to depict the intellectual and emotional highs and lows of developing a semiotic schema.