One in a series of posts dedicated to the author’s favorite semiopunk sci-fi. A version of each installment in this series first appeared at our sister site, HILOBROW.

In 1929, Olaf Stapledon (1886-1950) published A Modern Theory of Ethics, which articulates an eccentric, progressive philosophy, the elements of which include: ecstasy as a cognitive intuition of cosmic excellence, and the hopeless deficiency of human faculties when it comes to ascertaining the meaning of life, the universe, and everything. Although Stapledon wasn’t a science fiction fan, he’d go on to write several wildly imaginative, original Radium Age proto-sf novels that explores aspects of his philosophy.

The first of these, 1930’s Last and First Men, is an epic history of the future and meditation on the present, which he depicts as a tragic era during which only a few sensitive (therefore hapless and hopeless) individuals can even catch a glimpse of the possibility of cosmic consciousness. H.G. Wells was a fan, as were Jorge Luis Borges, Bertrand Russell, and Virginia Woolf. In the sequel Last Men in London (1932) we meet Humpty, a teenaged “supernormal” in whom there is “some promise of a higher type.” Things don’t end well for Humpty, but Stapledon wasn’t done with this trope yet.

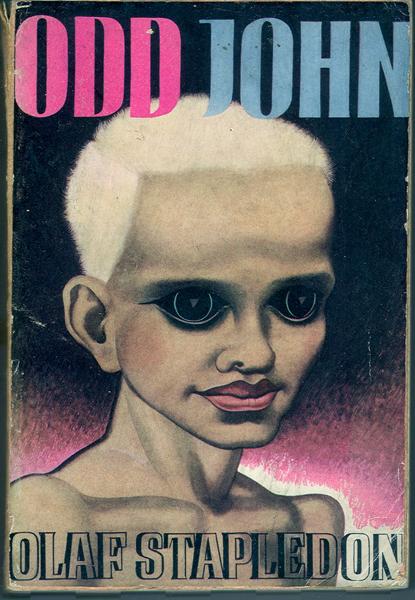

Stapledon’s Odd John (1935) gives us an entire cast of teenage mutant “supernormals” or “wide-awakes” — misfits who prefer not to get ahead, despise athletics, find religion and nationalism boring, don’t regard sex as shameful, and remain idealistic and utopian long after adolescence. Odd John is credited with introducing the expression homo superior, which would find its way into American sci-fi pulp fiction in the ’40s and ’50s; from there, it would be borrowed and popularized in the 1960s by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s X-Men comics.

Led by the titular Odd John, the cast of characters includes a 12-year-old Ethiopian boy, a 17-year-old Siberian girl, and a medieval superhuman who has died… but with whom Odd John neverthless can communicate. These teen titans, each of whom possesses a different superhuman ability, eventually form a utopian island colony where they experiment with telepathic communication, free love, a religion of “intelligent worship,” and a political economy of “individualistic communism.”

There’s so much to say about this book, but let’s zero in on its appeal for the semiotically minded. Odd John’s evolved consciousness and super-intelligence involves… pattern spotting. When young John is studying biology, for example, he suddenly tires of it. An adult character asks, “Have you finished with ‘life’ as you finished with ‘number?’”

“No,” replied John, “but life doesn’t hang together like number. It won’t make a pattern. There’s something wrong with all those books. Of course, I often see they’re stupid, but there must be something deeper wrong too, which I can’t see.”

Odd John is not only a pattern-seeker, but a pattern-maker. He draws up diagrams and charts that explain… everything. Yet Stapledon’ character is not merely a highbrow type. He’s a high-lowbrow, as concerned with physical pleasure and the splendors of nature, say, as he is with ideas.

He devised strange shapes which epitomized for him the tragedy of Homo sapiens, and the promise of his own kind. At the same time he was allowing the perceptual forms with which he was surrounded to work themselves deeply into his mind. He accepted with insight the quality of moor and sky and crag. From the bottom of his heart he gave thanks for all these subtle contacts with material reality; and found in them a spiritual refreshment which we also find, though confusedly and grudgingly.

Nor is Odd John a superhuman whose ultra-efficient intellect renders him as emotionless as a machine. He not only perceives unseen patterns and forces that are imperceptible to the rest of us; he is deeply affected by them too.

Sometimes he would listen intently to people’s voices; but not, apparently, for their significance, simply for their musical quality. He seemed to have an absorbing interest in perceived rhythms of all sorts. He would study the grain of a piece of wood, poring over it by the hour; or the ripples on a duck-pond. Most music, ordinary music invented by Homo sapiens, seemed at once to interest and outrage him; though when one of the doctors played a certain bit of Bach, he was gravely attentive, and afterwards went off to play oddly twisted variants of it on his queer pipe. Certain jazz tunes had such a violent effect on him that after hearing one record he would sometimes be prostrate for days. They seemed to tear him with some kind of conflict of delight and disgust.

For those of us who make a living surfacing and brooding over patterns, this story is nerdily gratifying. Alas, the world’s Great Powers eventually get wind of the mutants’ colony… and they join forces to conquer it.

I could have told you, Odd John, this world was never meant for one as beautiful as you.