One in a series of posts dedicated to the author’s favorite semiopunk sci-fi. A version of each installment in this series first appeared at our sister site, HILOBROW.

Science fiction author Jo Walton has called Robert Heinlein’s Friday (1982) “the worst book I love.” I agree with the sentiment. Friday is a picaresque that careens from one of Heinlein’s late-period obsessions to another, notably plural marriage and free love — which are not problematic in themselves… but Heinlein was no progressive. Prepare to be exasperated, and triggered. That said, the titular heroine is a kick-ass semiotician of sorts.

Friday Jones is a genetically modified Artificial Person, physically and mentally superior to ordinary mortals. A balkanized nation that will, as the book progresses, divide into the California Confederacy (“a fascist socialism designed by retarded schoolboys”), the Lone Star Republic (“a theocracy ruled by witchburners”), and the Chicago Imperium (“a crowd of hard-boiled pragmatists who favor shooting the horse that misses the hurdle”), twenty-first-century America can agree only that APs are second-class citizens without rights. So Friday conceals her true nature, while working as a combat courier for a shadowy organization.

Skipping over Friday’s episodic adventures, let’s focus on the book’s semiotics-esque interlude. Her boss, “Kettle Belly” Baldwin (whom Heinlein fans know from the 1949 novella Gulf), retires her from active duty. “Not all couriers have your supreme talent for instantly integrating all factors and reaching a necessary conclusion,” he explains. Friday is given various desk-based research and analysis assignments, which she carries out via an Internet-like system. It sounds fun:

The silly questions speeded up. I found myself just getting acquainted with the details of Ming ceramics when a message showed up in my terminal saying that someone in staff wanted to know the relationships between men’s beards, women’s skirts, and the price of gold. […] But I had learned not to ignore questions merely because they were obvious nonsense; I tackled this one by calling up all the data I could, including punching out some most unlikely association chains. I then told the machine to tabulate all retrieved data by categories. Durned if I didn’t begin to find connections! As more data accumulated I found that the only way I could see all of it was to tell the computer to plot and display a three-dimensional graph — and that looked so promising that I told it to convert to holographic in color. Beautiful! I did not know why these three variables fitted together but they did. I spent the rest of that day changing scales, X versus Y versus Z in various combinations — magnifying, shrinking, rotating, looking for minor cycloid relations under the obvious gross ones… and noticed a shallow double sinusoidal hump that kept showing up as I rotated the holo — and suddenly, for no reason I can assign, I decided to subtract the double sunspot curve. Eureka! As precise and necessary as a Ming vase!

Most semioticians aren’t as talented as Friday is when it comes to data crunching and visualization, of course. Nor do we get asked such questions. But this sort of thing — researching a large amount of stimuli, analyzing it for patterns, and arriving at a eureka! moment — that’s pretty much the job.

Once Friday has developed a formula, via abductive ratiocination (which her boss calls, as we’ve seen, “instantly integrating all factors and reaching a necessary conclusion”), she can proceed deductively and get answers for her client.

I fiddled for most of a day, waiting, and proving to myself that I could retrieve a group picture from any year and, through looking only at male faces and female legs, make close guesses concerning the price of gold (falling or rising), the time of that picture relative to the double sunspot cycle, and — shortly and most surprising — whether the political structure was falling apart or consolidating.

When she asks her boss what her new job title is, he responds: “You are staff intuitive analyst, reporting to me only. But the title carries an injunction: You are forbidden to discuss anything more serious than a card game with any member of the analytical section of the general staff.” The analysts are inductive and deductive types, one is led to assume. Boss doesn’t want Friday picking up any bad habits from them.

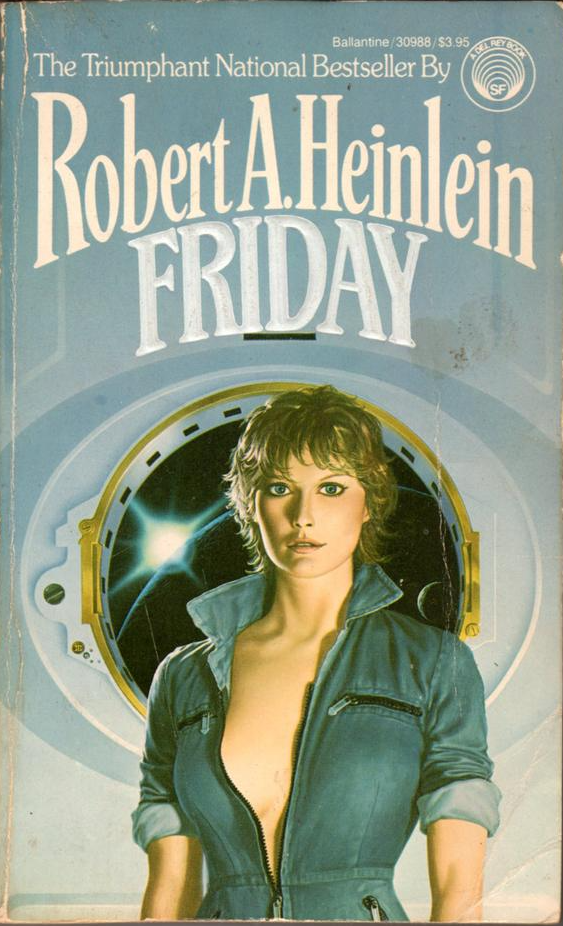

Alas, Friday’s agency is attacked, her boss dies, and she is forced to flee Earth. The pleasurable interlude ends all too quickly… but not before making an indelible impression on my adolescent brain. I devoured the book, c. 1983 — attracted, I’m sure, by the cover shown here. Friday’s nerdily gleeful approach to abductive analysis remains a key influence.