Iconic Mickey

As noted in previous installments of this series, once Mickey Mouse became popular with children worldwide, Disney began to sand the rough edges off MM’s persona. Both at the level of content and form, during the early part of the cultural era known as the Thirties (1934–1943) the character evolved from a child-like imp (scandalous, id-driven, loveable yet uncanny) into a childish ’toon (cheeky, playful, cute, sympathetic). Mickey was the first victim of the middlebrow-izing process that would later be dubbed Disneyfication — the process, that is, of stripping something of its eccentric true character, and sanitizing it.

Mickey Mouse became, at this point, a true icon. Some years ago, I wrote about what an “icon,” from a semiotic perspective — as opposed to a mere “symbol” — is. Excerpt:

[I]cons are meaning-bearing sign vehicles whose purpose it is — among humans and animals alike — to elicit or provoke, at a preconscious level, a particular space-time interaction. Ants, to employ an example favored by biosemiotics booster Thomas A. Sebeok, don’t choose to “milk” aphids for honeydew, but are impelled to do so by the iconicity of the aphid’s rear end (which, one should explain, apparently resembles an ant’s head). From a biosemiotic perspective, iconicity is about cognitive modeling, not communication.

During the Thirties, Walt Disney and his team reinvented Mickey Mouse as an icon intended to elicit at a preconscious level our hardwired instinct to adore that which is cute, innocent, cheery.

A 1934 magazine article under Walt Disney’s byline says that “I have tried give [Mickey] a soul and a ‘keep kissable’ disposition.” (Garry Apgar gushes: Mickey’s “eager, can-do attitude mirrored Disney’s own persona.”) It worked! In 1935 the League of Nations presented Walt Disney with a special medal recognizing that Mickey Mouse wasn’t merely a popular cartoon character, but nothing less than “a symbol of universal good will.” That same year, The New York Times Magazine described Mickey as “the best known and most popular international figure of his day.”

But Mickey’s persona makeover wasn’t enough, for Disney. In 1938, Disney animator Fred Moore redesigned the character’s look. White eyes with pupils replaced Mickey’s black pupils and undefined (enormous) eyes; the white parts of his face became “skin”-colored; his body became pear-shaped instead of round. “The change brought Mickey closer to us humans, but also took away something of his vitality, his alertness, his bug-eyed cartoon readiness for adventure,” writes John Updike in his introduction to The Art of Mickey Mouse (1991), a really useful and interesting book edited by Craig Yoe and Janet Morra-Yoe. “The original Mickey, as he scuttles and bounces through those early animated shorts, was angular and wiry, with much of the impudence and desperation of a true rodent.”

In the next installment of this series, I’ll take a look at Stephen Jay Gould’s anatomization of Mickey’s physical makeover. Here, let’s just ask ourselves why Disney transformed Mickey into an icon; and what the unintended consequences of doing so were.

Mickey became cute, innocent, and cheery because he’d become a cash cow. Now only were his movies huge draws, but MM merchandising was wildly lucrative.

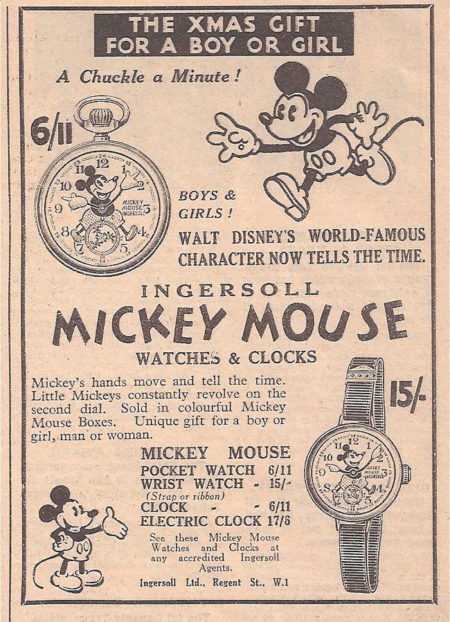

The Mickey Mouse wristwatch, manufactured by the Ingersoll-Waterbury Co. of Waterbury, which was widely publicized when it went on sale at the Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago in the spring of 1933, sold a million units in eight months. The New York Times Magazine said that “by himself” Mickey had restored “a famous but limping watch-making company to health”; Ingersoll added 2,700 workers to its payroll and proceeded to sell millions more Mickey Mouse watches.

In 1934, General Foods puts Mickey Mouse on the Post Toasties cereal box, making Mickey the first licensed character to appear on a cereal box. In 1935, Lionel introduced The Mickey Mouse Handcar train toy, with a circle of track. One million sets were sold in three years, saving Lionel from bankruptcy. There was also a Mickey Mouse comic strip in newspapers, a Mickey Mouse magazine, scores of Mickey Mouse books, Mickey Mouse bubblegum cards. In England, in 1936 Odhams Press first published Mickey Mouse Weekly; 375,000 copies of the first issue were sold. Cartier’s sold diamond-studded Mickey Mouse pins.

Garry Apgar’s useful, if often wrong-headed 2015 book Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit features scores of examples of just how wildy popular MM became during the 1934–1938 period. To mention just a few examples:

- 1934: Orphan’s Benefit (1934); MM mentioned in Rex Stout’s first Nero Wolfe mystery; Buddy Ebsen wears a MM sweatshirt in the movie Broadway Melody. See above for other 1934 examples.

- 1935: The Band Concert (Mickey’s first official color film, considered one of the best animated films of all time; and the apex — according to Garry Apgar — of MM’s “classical” visual persona), Mickey’s Fire Brigade; the Emperor of Japan wears a MM watch; Philo T. Farnsworth uses MM cartoons to demonstrate his invention: TV; Graham Greene praises Fred Astaire as “the nearest approach we are ever likey to have to a human Mickey Mouse.”

- 1936: Thru the Mirror, Moving Day; at a Paris ceremony attended by movie pioneer Louis Lumiere, Walt Disney awarded a medal for creating a “symbol of international goodwill”; a MM doll plays a role in Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times.

- 1937: Clock Cleaners (considered one of the best animated films of all time), Moose Hunters, Lonesome Ghosts (the original Ghostbusters).

- 1938: Brave Little Tailor (considered one of the best animated films of all time), Boat Builders, Mickey’s Trailer; Cary Grant references MM in the movie Bringing Up Baby.

When Cole Porter’s 1934 song “You’re the Top” included the line “You’re Mickey Mouse,” he was referring to Mickey’s popularity — his status as an icon — along with the Coliseum, the Louvre, a Shakespearean sonnet, the Mona Lisa, a Strauss symphony. That is to say, Mickey had ascended to a height at which ordinary judgement would be suspended. Like all icons, Mickey was now on a pedestal.

Apgar, making his case for Mickey Mouse as icon, claims that the term means “a being or thing touched by a vital spark, providing meaning, comfort, and connectedness across generational, ethnic, national, and class lines.” However, as I mused in the aforementioned SEMIONAUT essay, iconicity is a less comforting, more uncanny phenomenon than what Apgar is describing.

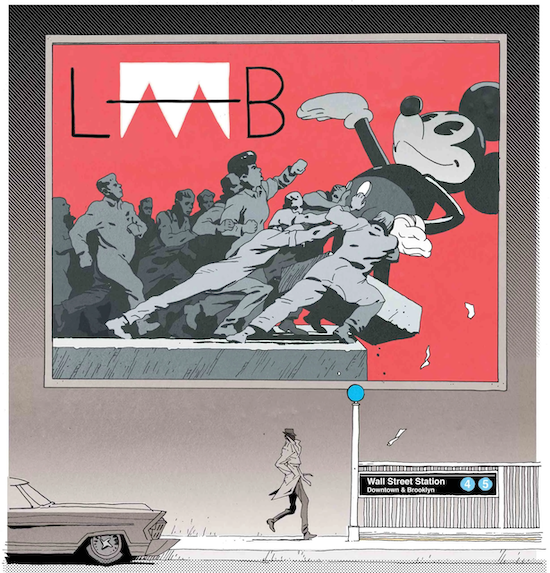

There’s something about a statue of a popular figure (on a pedestal) that almost demands — at a preconscious level — that we deface it, pull it down, behead it. When Saddam Hussein’s statue in Baghdad was yanked from its pedestal in 2003, HILOBROW friend Luc Sante wrote, in The Boston Globe, that the statue seemed “almost to will its own collapse.” I’m also thinking of Saul Steinberg’s 1958 New Yorker essay-drawing of a series of statues, each one featuring a triumphant new ruler standing over the corpse of the ruler celebrated by the previous statue.

What I’m getting at is this: Mickey’s meteoric rise to the status of icon would prove to have the unintended consequence of provoking the anti-Mickey backlash. It’s almost as though we couldn’t help it.