Yvonne

This is the sixth of eight installments in the series CASABLANCA CODES. See also the 2020 series CADDYSHACK CODES.

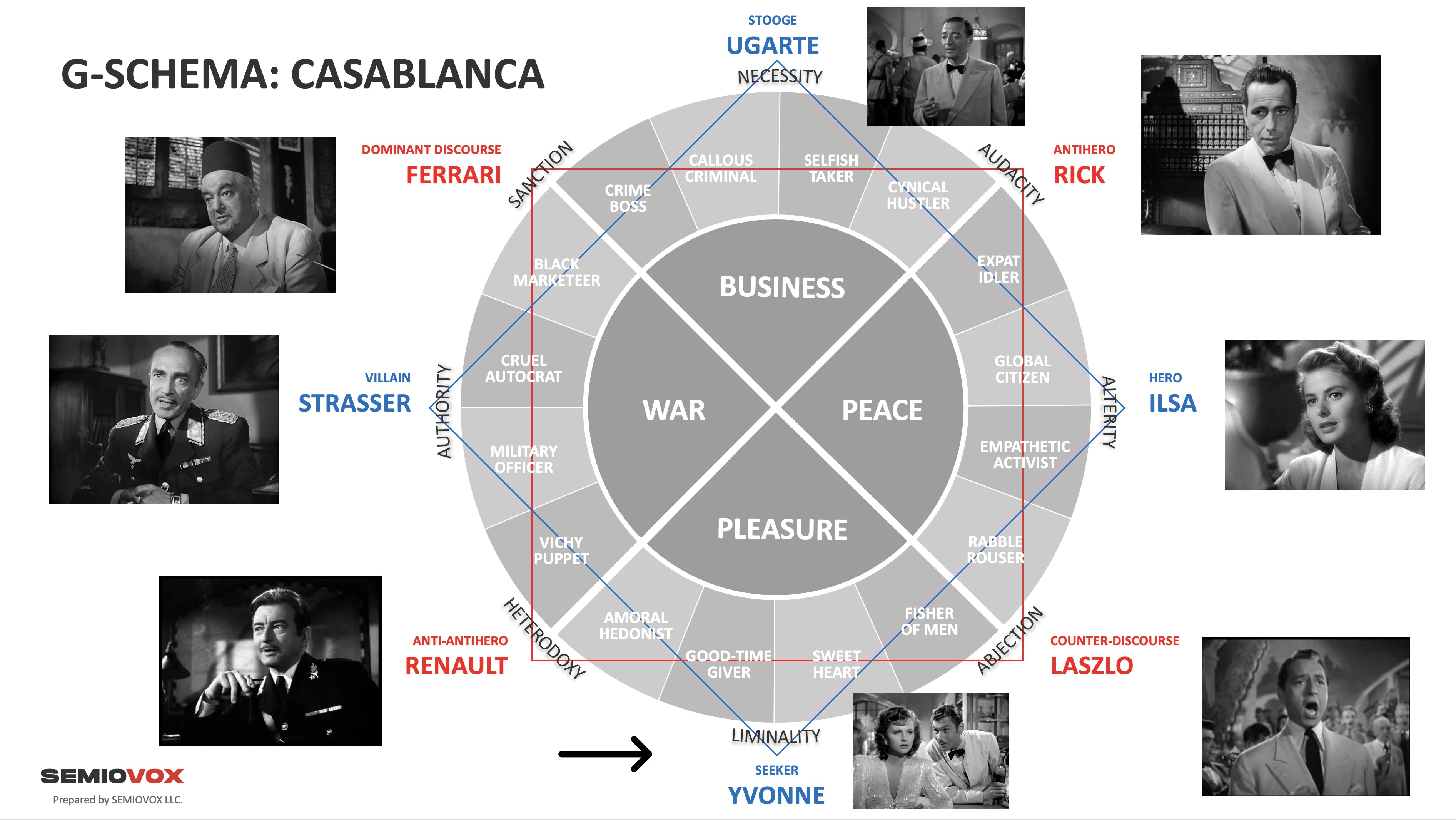

Thus far, the Casablanca semiosphere paradigms we’ve identified are: FERRARI (dominant discourse), LASZLO (counter-discourse), STRASSER (villain), ILSA (hero), and UGARTE (stooge). All of which is charted out via the Casablanca G-schema reproduced below.

We turn now to this semiosphere’s “seeker” paradigm… the final of four vertices from our G-schema’s second [it’s blue, in our chart] semiotic square. Once we’ve completed the second square, we can return to the first square and tackle the antihero vs. anti-antihero paradigms.

In this series’ previous installment, we explored Casablanca‘s two BUSINESS thematic complexes that are governed by UGARTE, the stooge paradigm. Structurally, a G-schema’s seeker paradigm is diametrically opposed to its stooge paradigm — and the same goes for their respective thematic complexes. Casablanca‘s seeker paradigm, then, governs the PLEASURE complexes SWEET HEART and GOOD-TIME GIVER.

Also, just as the stooge paradigm is torn between the conflicting demands of its adjacent paradigms, so is the seeker paradigm. Will they drift into the orbit of the paradigm RENAULT? Or into the orbit of LASZLO? Although the seeker is entirely consumed neither with WAR (as is Strasser), nor with PEACE (as is Ilsa), they’ll have to make a decision. Which mode of pleasure will win out?

The seeker is a liminal figure. In anthropology, liminality is the quality of ambiguity or disorientation that occurs in the middle stage of a rite of passage. A G-schema’s seeker is on a vision quest, a soulful mission — a journey that is as much internal as it is external. Unlike the stooge, deformed by his or her efforts to accommodate competing demands, the seeker is anguished by their efforts to decide who they are and what they stand for.

So which Casablanca character best fits the “seeker” bill? Our seeker character, who has only three scenes, each of which poignantly dramatizes and (finally resolves) this semiosphere’s dynamic tension, is: YVONNE.

In this installment, we’ll examine the thematic complexes governed by the YVONNE paradigm. But first, a few words about the actor who portrays Yvonne.

Madeleine Lebeau (1923–2016) was a French actress whose debut role was in 1939’s Jeunes filles en détresse. Having married the well-known Jewish character actor Marcel Dalio (La règle du jeu, La Grande Illusion), a much older man, in 1940 she fled France with him, one jump ahead of the invading German Army.

From Lisbon, Lebeau and Dalio made their way to Chile, then finally to America; they were stranded en route, however, when the visas they’d purchased turned out to be forgeries. So the plight of Yvonne and other refugees depicted in Casablanca is one with which Lebeau was familiar. As were other cast members, of course — including Conrad Veidt, Peter Lorre, S.Z. Sakall (Carl, the headwaiter), and Helmut Dantine (Jan Brandel).

Having learned English en route to America, Lebeau made her Hollywood debut in Hold Back the Dawn (1941), then the following year appeared in the Errol Flynn movie Gentleman Jim. She and Dalio were both cast in Casablanca; he plays Emil the croupier. (The two divorced in 1942.)

Though she would appear in twenty other movies, including La Parisienne (1957) and Fellini’s 8½ (1963), the Casablanca character Yvonne remains Lebeau’s iconic role. When she died, a few years ago, France’s culture minister announced: “She will forever be the face of the French resistance.”

GOOD-TIME GIVER

As shown on our Casablanca G-schema, the “stooge” thematic complex SELFISH TAKER is diametrically opposed by the “seeker” complex GOOD-TIME GIVER. Whereas Ugarte is a black hole of neediness, a taker who never gives, Yvonne, a refugee from occupied France, seeks only to give of herself. Unfortunately, she is attracted to the wrong men.

When we first encounter her, Yvonne is in Rick’s Café Americain, wearing a fabulous dress, guzzling brandy at the bar. The bartender, a Russian named Sacha, refills her tumbler and gazes at her amorously.

SACHA: The boss’s private stock. Because, Yvonne, I loff you.

YVONNE: Oh, shut up.

That “shut up” makes Yvonne seem like a callous “good-time girl” — a young woman who is primarily interested in pleasure and having a good time. Or a femme fatale.

Rick saunters over and leans on the bar, next to Yvonne. He pays no attention to her. She looks at him bitterly.

SACHA: Oh, Monsieur Rick, Monsieur Rick. Some Germans, boom, boom, boom, boom, gave this check. Is it all right?

Rick looks the check over and tears it up.

YVONNE: Where were you last night?

RICK: That’s so long ago, I don’t remember.

YVONNE: Will I see you tonight?

RICK: I never make plans that far ahead.

This is noir repartee. If Yvonne were in fact a good-time girl or femme fatale, we’d find this exchange humorous. But Yvonne seems wounded by Rick’s indifference; so Rick comes across as callous, even cruel, here.

One thinks of other antihero/seeker relationships, more bromantic (in the examples mentioned here) than romantic ones. Ty Webb and Carl Spackler in Caddyshack, for example: This semiosphere’s seeker (Carl) would dearly love to develop a close friendship with the antihero (Ty)… who is in fact incapable of friendship, and a preppie snob, and thus quite rude to Carl.

Or take Han Solo and Luke Skywalker in Star Wars. Not until the Battle of Yavin, i.e., the moment at which the Rebel Alliance destroys the Death Star, will Han think of Luke as anything but a farm boy with delusions of heroism. Even after this moment, Han will call Luke “kid” — putting him in his place.

Yvonne turns, looks at Sacha, and extends her glass to him.

YVONNE: Give me another.

RICK: Sacha, she’s had enough.

YVONNE: Don’t listen to him, Sacha. Fill it up.

SACHA: Yvonne. I loff you, but he pays me.

YVONNE: Rick, I’m sick and tired of having you —

RICK: — Sacha, call a cab.

SACHA: Yes, boss.

Rick takes Yvonne firmly by the arm.

RICK: Come on, we’re going to get your coat.

Again, Yvonne doesn’t come across as a typical good-time girl or femme fatale. Like Ugarte, she resents being man-handled and ordered around.

YVONNE: Take your hands off me!

Rick pulls her along toward the door.

RICK: No. You’re going home. You’ve had a little too much to drink.

Cut to the exterior of Rick’s. Sacha stands at the curb on the street and signals. A taxi pulls up. Rick and Yvonne emerge from the cafe. He puts a coat over her shoulders while she objects violently.

YVONNE: Who do you think you are, pushing me around? What a fool I was to fall for a man like you.

RICK: You’d better go with her, Sacha, to be sure she gets home.

SACHA: Yes, boss.

RICK: And come right back.

After this scene, Yvonne disappears from the movie. She won’t reappear until well into Act II. What have we learned about her? She isn’t a good-time girl; instead, she’s a good-time giver. She’s given of herself freely to Rick, expecting him to reciprocate. Instead, he’s remained hard-boiled, willfully numb. (He’s not unscrupulous, at least; he doesn’t take advantage of drunken Yvonne, nor will he allow Sacha to do so. If she were a femme fatale, Rick might have acted differently.) She’s fallen for the wrong fellow.

In what direction will the seeker swing, now? Towards the WAR territory, as represented by Renault? (After Yvonne drives off in the cab, Renault tells Rick that he might try to pick Yvonne up “on the rebound.”) Or towards the PEACE territory, as represented by Laszlo?

The answer, we’ll find, is: towards both. For better or worse, that’s the nature of the seeker.

SWEET HEART

In our Casablanca G-schema, the “stooge” thematic complex CALLOUS CRIMINAL is diametrically opposed by the “seeker” complex SWEET HEART. Whereas Ugarte is an utterly callous, amoral figure, we’ll soon discover that beneath Yvonne’s good-time girl exterior beats an ardent, yearning heart.

Yvonne returns to Rick’s place triumphantly, on the arm of a German officer. When it comes to pleasure, the seeker seems to have sworn allegiance to the WAR territory. “It looks like you’re a little late,” Rick remarks to Renault — who’d said he was planning to pick up Yvonne as she rebounded from Rick.

RICK: So Yvonne’s gone over to the enemy.

RENAULT: Who knows? In her own way she may constitute an entire second front.

Although Renault’s remark is intended to suggest that Yvonne is nothing but trouble, Renault is a Frenchman whose allegiance — to France, or to Germany — Rick is casually testing here. Renault seems to hope that Yvonne hasn’t “gone over to the enemy”… that, in fact, she’s acting as a kind of resistance guerrilla, whether or not she fully realizes it.

Note that in the movie’s Paris flashback, we hear the Germans announce:

“Hort aufmerksam zu! Die deutschen Truppen Stehen vor den Toren von Paris. Euer Aufstand ist ohne jegliche Verdeidigung, eure Ehre ist in Auflosung begriffen. Seid unbesorgt, wir werden Ruhe und ordnung weider herstellen.” Listen carefully! The German army stands before the gates of Paris. Your uprising is without any defense; your honor is disintegrating. Stay calm — we will restore peace and order.

Yvonne, it seems, has opted for peace and order with the German invaders rather than continue to allow her honor to be disintegrated. Or is she just hoping to make Rick jealous?

At the bar, Yvonne and the German officer place their orders.

YVONNE (rather drunkenly): Sacha!

GERMAN OFFICER: French 75s.

YVONNE: Put up a whole row of them, Sacha… starting here and ending here.

She indicates with her hand where she wants them.

GERMAN OFFICER: We will begin with two.

Germans — so literal! Sheesh.

PS: A French 75 is a cocktail — dating to the early 1920s — made from gin, champagne, lemon juice, and sugar. Essentially, it’s a Tom Collins with champagne instead of carbonated water. (In French it’s a soixante quinze.) The drink is named after the French 75mm field gun, used during World War I, due to its potency.

A French officer at the bar now makes a remark to Yvonne (in French): “Say, you — you are not French to go with a German like this!”

YVONNE (in French): What are you butting in for?

FRENCH OFFICER (in French): I am butting in —

YVONNE (in French): — It’s none of your business!

GERMAN OFFICER (in French): No, no, no, no! One minute! (in English) What did you say? Would you kindly repeat it?

FRENCH OFFICER: What I said is none of your business!

GERMAN OFFICER: I will make it my business!

They begin to fight.

YVONNE (in French): Stop! I beg of you! I beg of you, stop!

Again, if Yvonne were a femme fatale, this sort of ruckus is exactly what she would have intended to instigate. (And the brouhaha seems to confirm Renault’s glib remark about Yvonne constituting a “second front” — a situation where a third party opens a new battleground against an enemy that is already engaged in a war with another force.) However, warm-hearted Yvonne doesn’t actually want to see anyone get hurt.

The seeker in any semiosphere will often end up in a jam. They’re torn between their semiosphere’s dominant discourse and its counter-discourse. How to decide? They can’t. Instead, they oscillate between the semiosphere’s “poles,” whirling in a vortex of their own making. One thinks of an object with a magnetic moment caught in a magnetic field’s lines of force and “precessing” — rotating around and around.

Later that evening, Laszlo urges the band to play the “Marseillaise” — as a show of opposition to the Germans at Rick’s. Yvonne jumps up and sings her country’s anthem with tears in her eyes.

The song finishes on a high, triumphant note. Yvonne’s face is exalted. She faces the alcove where the Germans are watching, and shouts at the top of her lungs.

YVONNE: Vive La France! Vive la democracie!

CROWD: Vive La France! Vive la democracie!

Inspired by Laszlo, the seeker has made her decision: PEACE, not WAR.

This is our last glimpse of Yvonne. It is one that no viewer will ever forget.

Next CASABLANCA CODES series installment: RICK.

All series installments: FERRARI | LASZLO | STRASSER | ILSA | UGARTE | YVONNE | RICK | RENAULT.