Ugarte

This is the fifth of eight installments in the series CASABLANCA CODES. See also the 2020 series CADDYSHACK CODES.

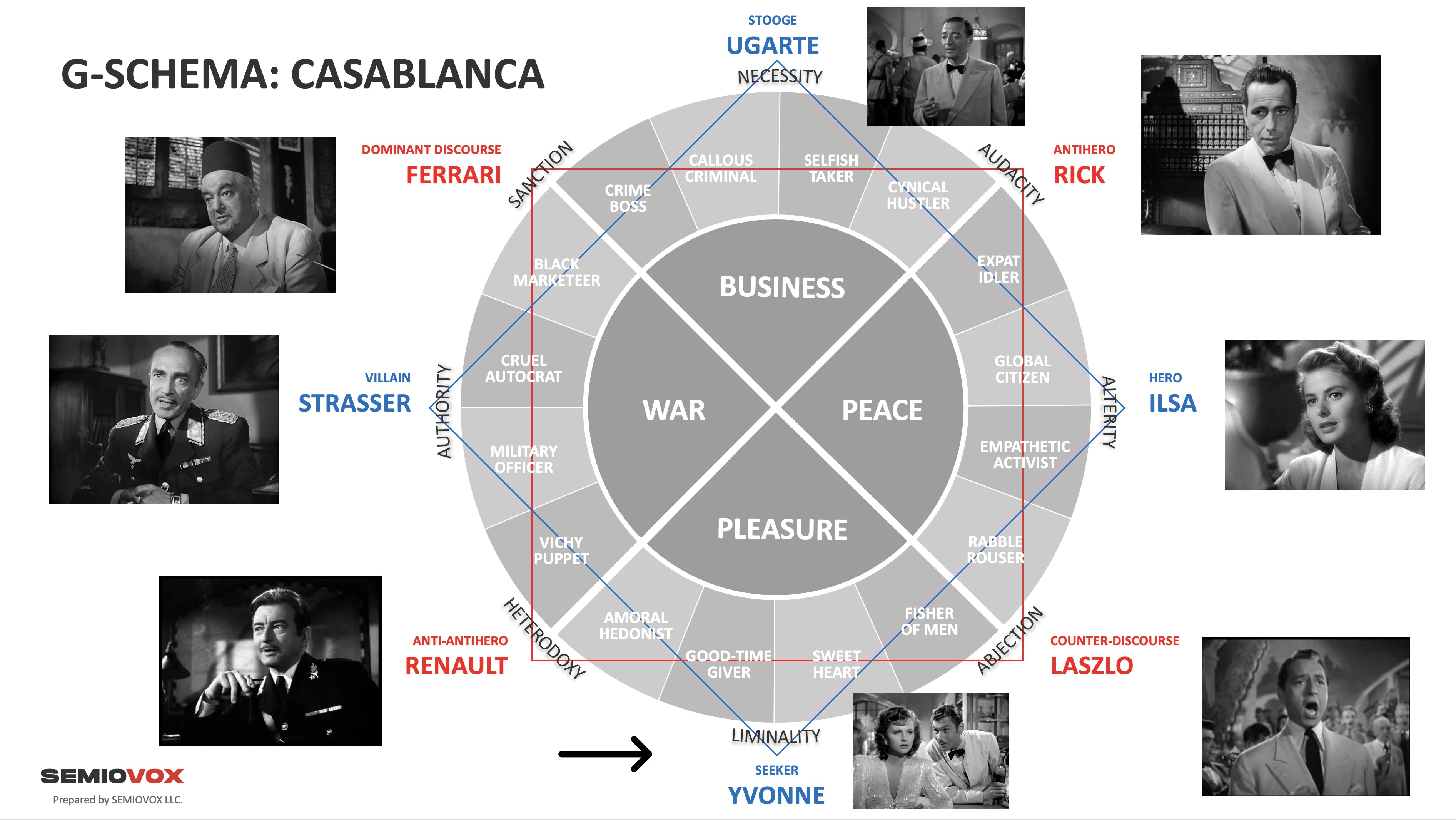

So far in this series, we’ve identified FERRARI as the Casablanca semiosphere’s dominant-discourse paradigm, LASZLO as its counter-discourse paradigm, STRASSER as its villain paradigm, and ILSA as its hero paradigm. All of which is charted out via the Casablanca G-schema reproduced below.

We turn now to the Casablanca semiosphere’s “stooge” paradigm… the third of four vertices that we’ll explore on our G-schema’s second [it’s blue, in our chart] semiotic square. This is our preferred way to proceed — first identify the opposing sanction/abjection paradigms, then the opposing authority/alterity paradigms, then the opposing necessity/liminality paradigms. We leave audacity/heterodoxy for last.

The stooge paradigm of a G-schema governs the “upper” of two territories adjacent to the territory governed by the semiosphere’s villain, and adjacent to the territory governed by its hero. As was explored in previous series installments, for the movie Casablanca, the villain’s territory is WAR, the hero’s PEACE. The Casablanca territory over which the stooge presides is: BUSINESS. Casablanca’s business-oriented characters — Ferrari, Rick, Ugarte — are entirely consumed neither with war (as Strasser is), nor with peace (as Ilsa is). Ugarte, alone among these three, is entirely consumed with — and deformed by — the business of Casablanca.

As noted in the series’ FERRARI installment, the business of Casablanca is about gambling and other vices; but it is also very much about smuggling refugees out of occupied Europe, for a fee. The hybrid paradigm RICK, positioned in both the BUSINESS and PEACE territories, won’t get involved in people-smuggling; but the hybrid paradigm FERRARI, positioned in both the BUSINESS and WAR territories, is heavily involved in it.

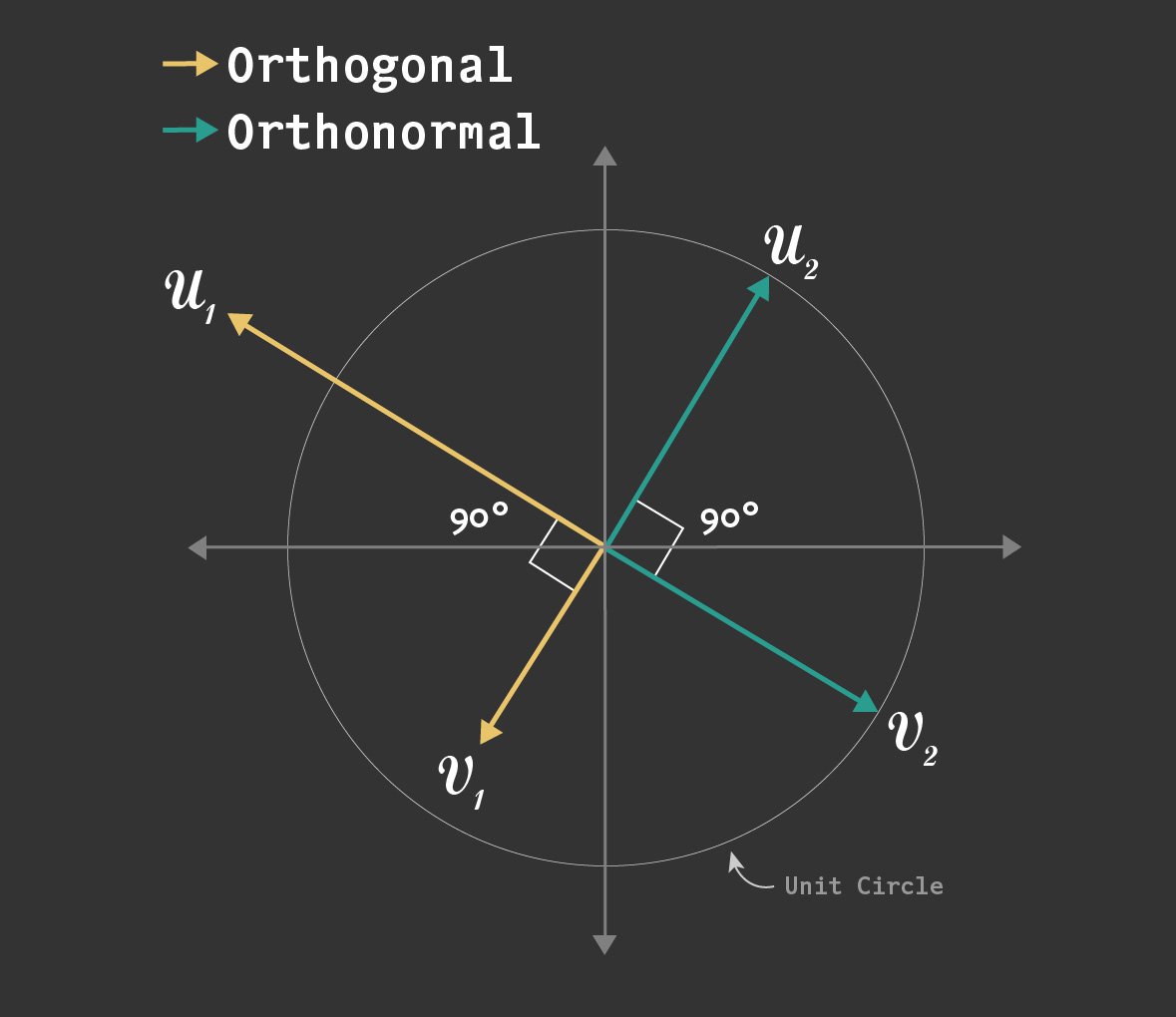

The BUSINESS territory is both literally (as a glance at our G-schema will reveal) and figuratively “orthogonal” to the territories WAR and PEACE. Let’s briefly investigate the nature of orthogonality within a G-schema.

The 16th-century term is a mathematical one — particularly in linear algebra and geometry. In Euclidean geometry, if two line segments are perpendicular (i.e., the angle between them is 90 degrees), then we can say that they are orthogonal, from the Greek ορθο, meaning literally “straight” or “upright,” and figuratively “right” or “true.”* In a G-schema, the stooge and villain paradigms are what geometers would describe as “mutually orthogonal” (or “pairwise orthogonal”) to each other; the same thing goes for the stooge and hero paradigms. Contrariwise, the same thing goes for the seeker paradigm vis-à-vis the hero and villain paradigms.

* Although the terms are often used as synonyms, one derived from Greek and the other from Latin, in fact orthogonality is the generalization of the geometric notion of perpendicularity. While the term orthogonality can refer to the relationship between any two objects that are at right angles to each other, the term perpendicularity is restricted to lines. One is tempted to use the latter term literally, then, and the former figuratively.

Mutually orthogonal paradigms are related yet wholly independent; a stooge’s actions may affect the hero or villain, but indirectly — and vice versa. The stooge paradigm, as we’ll see in Casablanca, is influenced directly neither by Strasser nor Ilsa; instead, this paradigm is influenced by its two adjacent paradigms — which are mutually “hemiorthogonal” (“hemigonal” for short), to coin a phrase. These paradigms are: the dominant discourse (i.e., FERRARI) and the antihero (i.e., RICK).

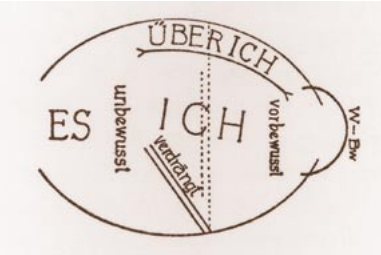

As I’ve noted before, the structural relations—in a G-schema—among the dominant discourse, stooge, and antihero paradigms (that is, the three vertices along our chart’s “upper” curve) bear comparison to the structural relations among what Freud described as the human psyche’s three interacting parts or entities: superego, ego, and id, respectively.

In Freud’s personality theory, the ego is deformed thanks to its efforts to mediate between the conflicting demands of the id and superego. No man, or so the Bible tells us, can serve two masters. The ego is an enabler, of sorts, trapped in a self-destructive pattern of trying to appease these two masters. As I wrote in the essay linked to above:

The paradigms that turn up in a G-Schema’s top-vertex position, I’ve found, may appear confident and reasonable (the ego is all about projecting confidence and reasonableness) but in fact they’re faking it.

Hence the pathos of a stooge. A pathos that helps explain why we feel sympathy for a stooge. Because we often equate our ego with our true self. Excessive or unhealthy ego identification can lead to negative outcomes, including arrogance, difficulty empathizing with others, and a tendency to be defensive or self-centered. Stooge qualities, every one.

We’re ready to name names. Which Casablanca character is independent of Strasser and Ilsa, and torn between Ferrari and Rick? Which Casablanca paradigm is deformed thanks to its efforts to mediate between the dominant discourse and antihero paradigms? Which character is a hustler, a schmoozer, a schlemiel, and (literally, schema-wise) a middleman — that is to say, a stooge? Our stooge is: UGARTE.

In this installment, we’ll examine the thematic complexes governed by the UGARTE paradigm. Let’s pause, though, to commemorate the actor portraying Signor Ugarte.

Peter Lorre (László Löwenstein, 1904–1964) was a Hungarian-born actor who found fame on the stage (including in Bertolt Brecht’s plays), then in film, in Berlin during the late 1920s and early 1930s. He caused a global sensation in Fritz Lang’s film M (1931), where he portrayed a serial killer of little girls. He was also terrific as a courtly villain in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and an antihero in Secret Agent (1936).

Lorre, who was Jewish, left Germany after Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power. Eventually settling in Hollywood, he portrayed Mr. Moto, a Japanese detective, in a series of B-pictures; and he became a featured player in Warner Bros. crime and mystery films. John Huston cast Lorre in The Maltese Falcon (1941), the success of which led to several movies — including Casablanca — reuniting him with Humphrey Bogart, Sydney Greenstreet, and/or Claude Rains. In the last decade of his career, Lorre would often play creeps in films such as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), not to mention Roger Corman’s Tales of Terror (1962) and The Raven (1963).

As I’ve written elsewhere, Lorre is a sympathetic villain because he portrays his characters as desiring what we all desire, particularly in a brutalizing, fascist social order: respect, equality, fair treatment. As my own country heads in an ever more fascist direction, I can relate.

CALLOUS CRIMINAL

In our Casablanca G-schema, the stooge thematic complex CALLOUS CRIMINAL is diametrically opposed by the seeker complex SWEET HEART. Ugarte is the opposite of a sweetheart. Although courageous, wily, and oddly sympathetic, Ugarte is an utterly callous, amoral figure.

An Italian who’s wound up in Casablanca, Ugarte has survived by selling exit visas to desperate refugees via the city’s black market. He’s a less-expensive, and no doubt less reliable version of Ferrari. As a result, whereas Rick displays a kind of cynical respect for Ferrari’s business acumen, he looks down his nose (literally) at Ugarte.

This dynamic between the two characters is made apparent when Ugarte first appears. Rick, at that moment, is occupied with kicking an influential German — perhaps, Ugarte suggests, someone involved with the Deutsche Bank, which viewers would have recognized as a Nazi institution responsible for processing wealth stolen from Jews — out of his casino.

UGARTE: Uh, excuse me, please. Hello, Rick.

RICK: Hello, Ugarte.

UGARTE: You know, Rick, watching you just now with the “Deutsches Bank,” one would think you’d been doing this all your life.

RICK: Well, what makes you think I haven’t?

UGARTE: Oh, nothing. But when you first came to Casablanca, I thought —

RICK: — You thought what?

Ugarte laughs self-deprecatingly.

UGARTE: What right do I have to think?

Ugarte is behaving obsequiously, unctuously — he is truckling to Rick. Does he do so out of actual respect, or in order to get something over on Rick? A little bit of both, one suspects. Freud compared the ego, in its relation to the id, to a man on horseback: the rider must harness and direct the superior energy of his mount, and at times allow for a practicable satisfaction of its urges. Ugarte’s opening gambit, in this scene, appears intended to remind Rick of his (Rick’s) anti-fascist past — so that Rick will be impressed with Ugarte’s murder of the German couriers… and will therefore do Ugarte a big favor. But when Rick kicks against this effort to harness and direct his energies, Ugarte immediately eases up on the reins.

Note that Ugarte seems to possess keen insight into Rick’s character. Though Rick may want others (and himself) to believe that he is a profit-driven shark no different than Ferrari, well… thanks to his positioning, Ugarte has a clear POV on the difference between the two men.

Ugarte sits down, uninvited, at Rick’s table, and tries a different gambit.

UGARTE: Too bad about those two German couriers, wasn’t it?

RICK: They got a lucky break. Yesterday they were just two German clerks. Today they’re the “Honored Dead.”

UGARTE: You are a very cynical person, Rick, if you’ll forgive me for saying so.

RICK: I forgive you.

A waiter comes up to the table with a tray of drinks. He places one before Ugarte. Ugarte offers to buy Rick a drink too. Rick, who is more interested in his solo chess game than in Ugarte, refuses. We’ll examine other aspects of this conversation in this installment’s second section. Here, where we’re discussing Ugarte’s callous criminality, let’s jump ahead:

UGARTE: Well, Rick, after tonight I’ll be through with the whole business, and I am leaving finally this Casablanca.

RICK: Who did you bribe for your visa? Renault or yourself?

UGARTE: Myself. I found myself much more reasonable.

He takes an envelope from his pocket and lays it on the table.

UGARTE: Look, Rick, do you know what this is? Something that even you have never seen. Letters of transit never seen, signed by General de Gaulle. Cannot be rescinded, not even questioned.

Rick, finally intrigued by Ugarte, appears ready to take a look.

UGARTE: One moment. Tonight I’ll be selling those for more money than even I have ever dreamed of, and then, addio Casablanca! You know, Rick, I have many friends in Casablanca, but somehow, just because you despise me you’re the only one I trust. Will you keep these for me? Please.

Ugarte is making a cold-blooded confession, here. He murdered the German couriers and stole the letters of transit. His confession had nothing to do with guilt — or any question of right or wrong, good or evil. He confesses his crime simply because he wants Rick’s respect… as we’ll discuss below.

Note the echo, in Star Wars, of Ugarte’s “more money than even I have ever dreamed of,” and this exchange between Luke Skywalker and Han Solo:

LUKE: “If you were to rescue her, the reward would be…”

HAN: “What?”

LUKE: “Well, more wealth than you can imagine.”

HAN: “I don’t know. I can imagine quite a bit.”

This comparison helps us to understand Ugarte’s rhetoric, here. He is attempting to speak with an antihero’s cynical, almost nonchalant swagger about great wealth.

That night, as Ugarte stands at the roulette table, gendarmes approach him and ask him to come with them. Ugarte asks permission to cash in his chips, then makes a break for it. Slamming the door between the casino and the nightclub, he draws a pistol and fires through the door. Dashing through the hallway, he spots Rick.

UGARTE: Rick! Rick, help me!

RICK: Don’t be a fool. You can’t get away.

UGARTE: Rick, hide me. Do something! You must help me, Rick. Do something!

Gendarmes rush in and grab Ugarte. Rick stands impassively as they drag him off.

UGARTE: Rick! Rick!

This is the last we’ll see of Ugarte. Later in the film, we’ll learn — though no evidence is provided — that Ugarte has, as the saying goes, “cashed in his chips.”

Though the stooge may strive to impress and accommodate the dominant discourse and antihero paradigms, the reverse is never true. The stooge’s hemigonal paradigms resent the stooge for thwarting their desires, and at the same time despise the stooge for their obsequious efforts to help them realize their desires.

A stooge can never win.

SELFISH TAKER

As shown on our Casablanca G-schema, the “stooge” thematic complex SELFISH TAKER is diametrically opposed by the seeker complex GOOD-TIME GIVER. Indeed, Ugarte is a black hole of neediness — sucking down cigarettes, gambling, doing whatever it takes (robbery, murder) to make enough money to leave Casablanca. He even orders a second drink before he’s started on his first. A stooge is so thirsty.

In Star Wars, Uncle Owen is the stooge paradigm. We never see him interact with the dominant discourse paradigm (stormtroopers, who murder him in the end), nor the antihero paradigm (Han Solo). But we get a sense of how “thirsty” this moisture farmer is whenever Luke suggests that he might want to leave the farm and join the Imperial Academy, to become a fighter pilot. “The harvest is when I need you the most,” Owen says to him — his manner simultaneously demanding and pleading. “You must understand I need you,” he reiterates. Owen’s needs are all that matters.

As thirsty as he may be for other rewards, Ugarte actually grovels for the sort of respect that Rick shows Ferrari. In the FERRARI installment, I wrote:

Respect and honor are […] the currency in which fictional crime bosses — “Dons” — deal amongst themselves. Theirs is a tribal-esque social order, we’re given to understand, one characterized by “total prestations,” to use Mauss’s descriptor for potlatches and other competitive exchange practices via which high-status sociocultural roles are maintained. In this crime-dominated semiosphere, then, respect is the most precious commodity to be found in the BUSINESS territory.

Although they may not actually like one another, Rick and Ferrari demonstrate mutual respect through a variety of gestures and rituals; they are rivals and equals. Let’s return now to the first scene that Rick and Ugarte share.

Ugarte has offered Rick a drink, and Rick has curtly rejected the offer. Though he’s in the same line of business as Ferrari, Rick shows no respect for Ugarte. He’s not even willing to look up from his chess puzzle to meet Ugarte’s beseeching gaze.

UGARTE: I forgot. You never drink with… (to waiter) I’ll have another, please. (to Rick, sadly) You despise me, don’t you?

RICK: If I gave you any thought, I probably would.

UGARTE: But why? Oh, you object to the kind of business I do, huh? But think of all those poor refugees who must rot in this place if I didn’t help them. That’s not so bad. Through ways of my own I provide them with exit visas.

RICK: For a price, Ugarte, for a price.

UGARTE: But think of all the poor devils who cannot meet Renault’s price. I get it for them for half. Is that so parasitic?

RICK: I don’t mind a parasite. I object to a cut-rate one.

Rick’s responses offer us keen insight into the nature of the structural relationship of stooge and antihero. While the antihero’s opinion is all-important to the stooge, the antihero doesn’t even think about the stooge… except to despise them. Also, the stooge misjudges what it will take to earn the antihero’s respect. Rick respects Renault, who also sells exit visas, so Ugarte insists that he’s doing the same work. Rick is (or was) sympathetic to authoritarianism’s victims, so Ugarte hypocritically suggests that his low, low prices are, in a way, humanitarian. These rhetorical efforts fall flat. In the cut-throat BUSINESS territory, “cut-rate” prices aren’t worthy of respect.

(Compare, from our previous series on CADDYSHACK CODES, the stooge Judge Smails’ misguided, hopeless efforts to earn the respect of antihero Ty Webb.)

It’s not until Ugarte reveals himself as a (literal) cutthroat that Rick changes his tune.

UGARTE: Rick, I hope you are more impressed with me now, huh? If you’ll forgive me, I’ll share my good luck with your roulette wheel.

He starts across the floor.

RICK: Just a moment.

Ugarte stops as Rick comes up to him.

RICK: Yeah, I heard a rumor that those German couriers were carrying letters of transit.

UGARTE: Huh? I heard that rumor, too. Poor devils.

Rick looks at Ugarte steadily.

RICK: Yes, you’re right, Ugarte. I am a little more impressed with you.

Though Ugarte won’t ever get his hands on those large sums of money he’s dreamed about, nor will he make it out of Casablanca alive… his story does have a kind of happy ending. The stooge has earned the antihero’s respect. If only for a moment, Ugarte’s thirst is quenched.

Next CASABLANCA CODES series installment: YVONNE.

All series installments: FERRARI | LASZLO | STRASSER | ILSA | UGARTE | YVONNE | RICK | RENAULT.