One in a series of posts dedicated to the author’s favorite semiopunk sci-fi. A version of each installment in this series first appeared at our sister site, HILOBROW.

Some 40,000 years from now here on Earth, humankind will have evolved beyond any need for our cultures and traditions, even our bodies — so we will have transcended the mortal plane entirely.

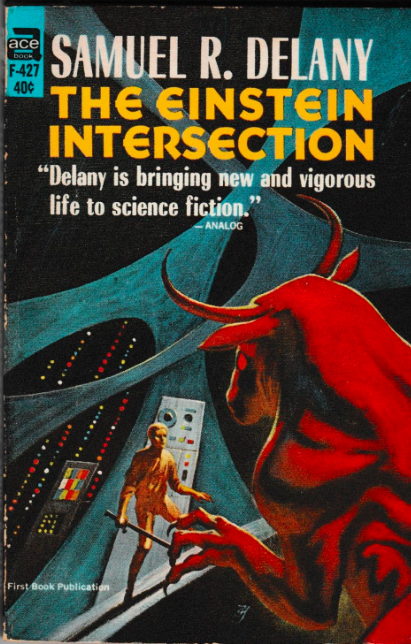

Lo Lobey, the protagonist of Samuel R. Delany’s 1967 sci-fi novel The Einstein Intersection, is a 23-year-old, brown-skinned goat herder and musician who — over the course of this weird and wonderful story — will discover that he is not a human. Like Earth’s other human-like inhabitants, he is a member of a wandering alien race that long ago adopted humankind’s norms and forms, not to mention our artifacts and stories… despite the fact that none of these are a proper fit for a mutable, three-gendered species.

Which is no doubt what it felt like to be Delany, a queer, Black 22-year-old, in 1967.

The plot of The Einstein Intersection, which would win the Nebula Award for best sf novel of that year, concerns Lobey’s exploration of humankind’s mythologies — from Orpheus and Eurydice to Billy the Kid and the Beatles (the keepers of “the great rock and the great roll”). All of which has become mixed-up. Delany’s deeper concern, however, is to depict how those of us who are wired “wrong,” in one way or another, thrash about (fruitfully or fruitlessly) within the meshes of our culture’s dominant discourse.

Lobey’s journey of understanding begins when his mate, La Friza, dies. (This alien species’ pronouns are “lo,” “la,” and “le.”) Like Orpheus, whose myth — among others — he is unwittingly recapitulating, Lobey sets off to see if he can’t somehow restore his beloved to life. Among the memorable characters he’ll encounter are Spider, an evolved alien (“different,” as they’re known) who uses his telekinetic powers to herd dragons, and who becomes a kind of guide; the sweet prince-in-exile Greeneye, a Christ-like different who performs miracles; Dove, a ubiquitous sex symbol; and Kid Death, the novel’s antagonist — a mocking, child-like, Billy the Kid-recapitulating different who murders other mutants with his mind.

The novel’s title is explained via Spider, who suggests to Lobey that Einstein’s theory of relativity only became truly helpful to humankind once it intersected with Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, a “mathematically precise statement about the vaster realm beyond the limits Einstein had defined.” Spider expands on this intriguing notion like so:

In any closed mathematical system — you may read ‘the real world with its immutable laws of logic’ — there are an infinite number of true theorems — you may read ‘perceivable, measurable phenomena’ — which, though contained in the original system, can not be deduced from it — read ‘proven with ordinary or extraordinary logic.’ Which is to say, there are more things in heaven and Earth than are dreamed of in your philosophy, Horatio.

The “intersection” between Einstein and Gödel’s theories was, we’re given to understand, an inflection point in humankind’s history. Once enough humans came to comprehend the irreality of the “real world,” they figured out how to transcend it altogether. So will Lobey’s species — hampered by ill-fitting human bodies and hindered by our outmoded mythologies — figure out how to liberate themselves too? And will we, Delany’s readers, hampered and hindered in much the same ways, also aim to liberate ourselves?

Short of actual transcendence, or so my reading of Delany’s story suggests, Lobey’s species must come to an understanding of its true (fluid) nature, and develop new and improved (highly flexible) ways of living together… rather than merely aping traditions inherited from the past.

Semioticians understand that each of us inhabits a cultural system the lineaments of which are invisible, inherited, and seemingly natural and inevitable. Our perceptions are warped by this system, our values and decisions influenced by it, our actions to some extent guided by it. We’ve inherited it, but we don’t entirely understand it, nor do we recognize how un-free we are… because we can’t “see” it. Like Lobey and his fellows, we are mutable, fluid creatures restricted and restrained by a system alien to us.

Myths can and will control us… unless we study how myths work, and use that knowledge to write our own stories.

The Golden Age sf author James Blish (whose undergraduate degree was in microbiology and who’d worked as a science editor for Pfizer) turned up at the Nebula Awards ceremony honoring The Einstein Intersection to register a complaint about Delany’s exploration of myth.

By definition, The Einstein Intersection is not science fiction, Blish insisted. Myth, which explains the world “in terms of eternal forces which are changeless,” an explanation that is “antithetical to the suppositions of science,” he groused, belongs instead to the fantasy genre. Fantasy writers may claim that we are controlled by myth; sf writers, or so Blish insisted, ought instead to subscribe to the scientific notion that we can analyze the forces at work in our lives and become masters of our destiny.

I don’t agree with Blish’s rigid definition. Fantasy and sf are, and always have been, coterminous; gatekeeping of this pernicuus sort was endemic to sf’s so-called Golden Age. Going along with his argument, however, we could perhaps describe semioticians as Delany-esque “differents.” Semios operate at the intersection (if you will) of fantasy and science fiction. Like the authors of fantasy, we understand myth to be a potent source of imperceptible forces to which we are acculturated to adapt; like the authors of science fiction, at the same time, we analyze myth and seek ways to subvert and evade its power. We’re neither as passive as the fantasy author, perhaps, nor as arrogant (and naive) as the science fiction author.

Lobey’s quest will take him into the dimension of myth — his culture’s “underworld,” literally. The most amazing part of the book is the extended sequence in which he hunts and battles a minotaur (except it’s human from the waist down, not the other way around) in a radioactive underground maze. A perilous adventure that allows him to discover — from an oracular super-computer, PHAEDRA [Psychic Harmony Entanglements and Deranged Response Association] — that his species is “a bunch of psychic manifestations, multi-sexed and incorporeal… trying to put on the limiting mask of humanity.”

We need to enter the labyrinth of our culture’s dominant discourse, and grapple with what we discover there. Yet in doing so we shouldn’t lose sight of the ultimate goal of our quest. Interpreting the world, in various ways, can become an addictively pleasurable pursuit. The point, however, is to change it.