One in a series of posts dedicated to the author’s favorite semiopunk sci-fi. A version of each installment in this series first appeared at our sister site, HILOBROW.

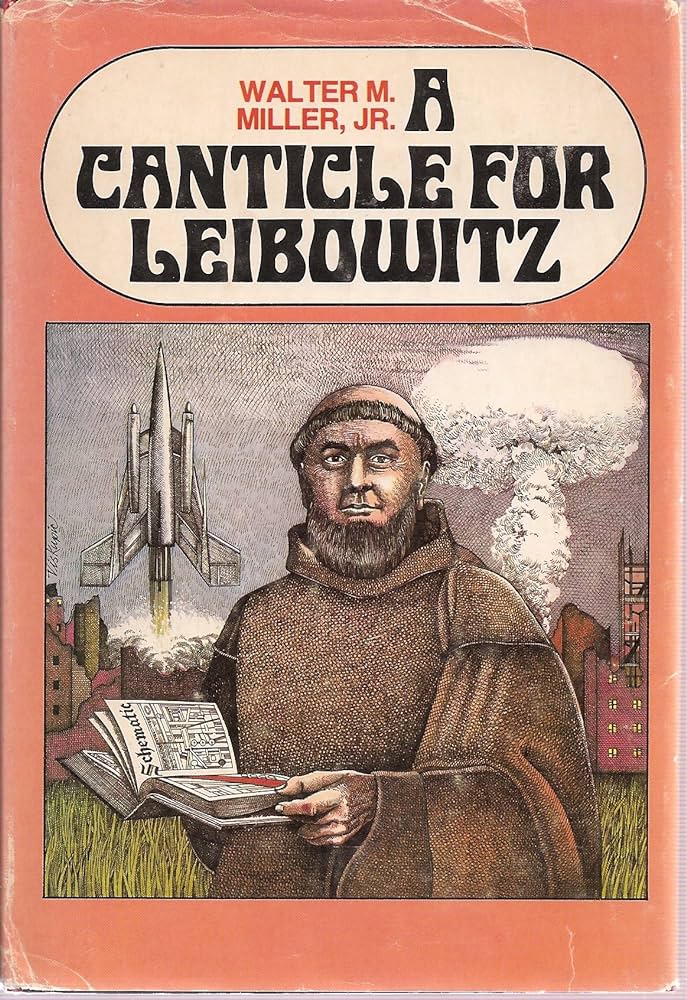

Humankind, some six centuries after the”Flame Deluge,” has devolved into a new Dark Age. Thanks to the “Simplification” (a post-apocalyptic reaction against science, technology, and education in general), one of the key repositories of pre-apocalyptic books and documents has ended up at an isolated monastery in what we’ll learn is the desert of what was once the southwestern United States. The amusingly named Order of Leibowitz is a collective of humble, devout, industrious Catholic monks dedicated to preserving, recopying, and illuminating the texts bequeathed to them by their order’s founder. Thus begins Walter M. Miller’s Hugo Awrd-winning 1959 novel A Canticle for Leibowitz.

Isaac Leibowitz, we’ll eventually figure out, was a Jewish former weapons engineer turned Catholic monk and “booklegger,” who risked life and limb to squirrel away humankind’s scientific and technical knowledge at the monastery. Which is a serene haven surrounded by “Simpletons” (radiation-warped mutants) scrabbling to eke out a living in the wasteland. The monks’ current inability to comprehend the texts they piously regard — half a millennium after the disaster — as sacred relics is amusing and tragic.

Does the sci-fi conceit of future archaeologists, historians, and scholars puzzling over fragments of 20th-century Western culture, after an intervening Dark Age, originate here? No: One can find earlier examples in, say, Valery Bryusov’s 1899 poem “The Days Shall Come of Final Desolation,” and Radium Age post-apocalyptic tales by the likes of Jack London (The Scarlet Plague, 1912), Edward Shanks (The People of the Ruins, 1920), Cicely Hamilton (Theodore Savage, 1922), and Edgar Rice Burroughs (The Moon Maid, 1926). Also, before and right around the time Miller started publishing (from 1955–57) the stories that would become A Canticle for Leibowitz, during science fiction’s so-called Golden Age one finds such examples as George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides (1949), Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), and Leigh Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow (1955). However, I wouldn’t include any of these precursors in the Semiopunk canon. For us semioticians there’s something particularly enchanting about the way Miller frames the story: monks faithfully preserving texts they can’t comprehend (and which could lead to disaster), the religious context and ecclesiastical politics, the culture of the monastery — is charming.

I should mention here, perhaps, that during World War II, Miller served as a radioman and tail gunner in a bomber crew that participated in the destruction of a famous abbey at Monte Cassino, Italy. The bombing became a source of significant regret and contributed to what might now be diagnosed as PTSD. MIller’s war experiences and their moral implications led to his conversion to Catholicism for a time; and when he was writing the first part of A Canticle for Leibowitz, as he’d later recount, “a light bulb came on over my head: ‘Good God, is this the abbey at Monte Cassino? … What have I been writing?'”

The book’s Part 1, “Fiat Homo”, was adapted from a short story published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (April 1955). Francis, a bumbling novice, discovers a fallout shelter used by Leibowitz — a former Los Alamos engineer “martyred” for his efforts to safeguard scientific knowledge during the Simplification. For Francis’s fellows at the Leibowitzan Order, the contents of the shelter are momentous. They collect, and begin to transcribe, what they call the “Leibowitz Memorabilia.” It’s a terrific story, full of nice details — the calm of the monastery’s cloisters, the books preserved in sealed barrels, the roving mutants. What this reader finds so appealing is the monks’ halting exegesis of Leibowitz’s memorabilia — technical documents, circuit diagrams, even a shopping list.

It’s a tragicomic situation. Francis toils over an an illuminated manuscript of a Leibowitz blueprint titled “STATOR WNDG MOD 73-A 3-PH 6-P 1800RPM 5-HP CL-A SQUIRREL CAGE.” Which he imagines to be a religious document of some sort. What a colossal waste of effort! And yet… the unintended consequence of the monks’ acts of religious devotion is the preservation of scientific knowledge — some of it much more momentous, as we’ll discover, than a “squirrel-cage” induction motor.

Part 2, “Fiat Lux,” adapted from “And the Light is Risen” (a novella published in F&SF in August 1956), takes place in the 32nd Century. At this point humankind has emerged out of the Simplification. Resurgent secular scientists are feuding with the information-hoarding Church over the control and distribution of technology. Powerful city-states (Denver, Texarkana, Monterey) run by warlords play both sides off against each other. It’s the Renaissance all over again. Thon Taddeo, a prominent scientist, visits the monastery, and is persuaded that the Leibowitz Memorabilia will lead him to breakthroughs. Part 3, “Fiat Voluntas Tua” (adapted from a novella published in F&SF in February 1957) is set in 3781. The Leibowitzan Order’s mission has expanded to the preservation of all knowledge. Space travel between earth and distant colonies has become common. Humankind is once again a highly technological species… but, frustratingly, nuclear apocalypse once again looms.

I’ll leave you in suspense about what happens from there. Let’s return instead to the book’s first section. Puzzling over cultural fragments that we cannot immediately comprehend, yet diligently — even faithfully — sticking with the long, arduous process of decoding and reassembling, in hopes of eventual “illumination”… OK, yes — one can draw certain parallels between the semiotician’s and the monk’s work. Like Francis, we do what we do because we love to contribute, in some small way, to human knowledge. But we can’t forget that our clients, like Thon Taddeo, may end up using our work for good or evil….