Renault

This is the eighth of eight installments in the series CASABLANCA CODES. See also the 2020 series CADDYSHACK CODES.

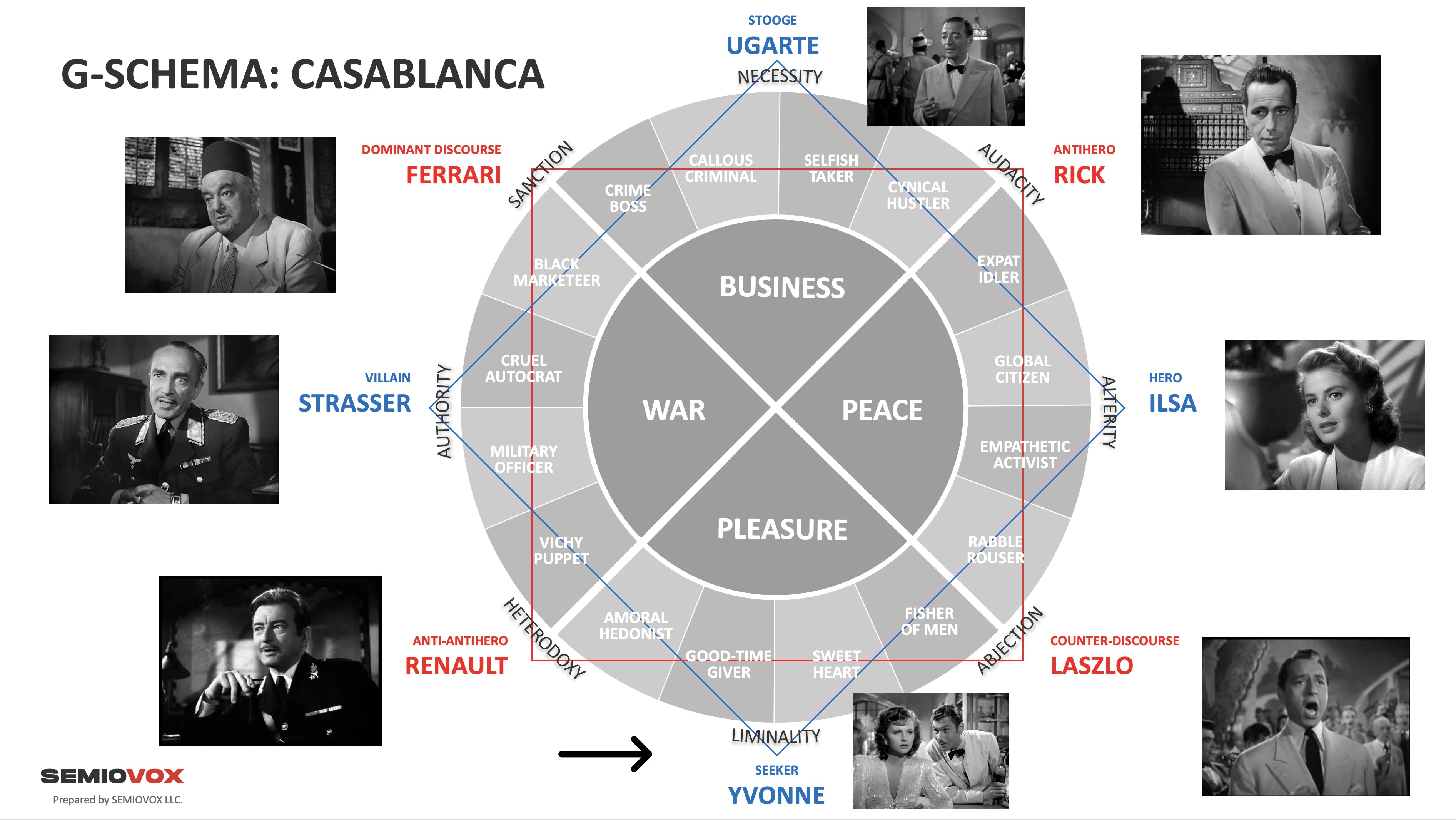

Thus far, the Casablanca semiosphere paradigms we’ve identified are: FERRARI (dominant discourse), LASZLO (counter-discourse), STRASSER (villain), ILSA (hero), UGARTE (stooge), YVONNE (seeker), and RICK (antihero). All of which is charted out via the Casablanca G-schema reproduced below.

We turn now to this semiosphere’s final paradigm, the “anti-antihero.”

An anti-antihero paradigm is “bordered,” in any G-schema, by the schema’s villain and seeker paradigms. Specifically, in this case, the Casablanca anti-antihero’s VICHY PUPPET thematic complex abuts the villain’s MILITARY OFFICER complex, while the Casablanca anti-antihero’s AMORAL HEDONIST complex abuts the seeker’s GOOD-TIME GIVER complex.

Casablanca’s anti-antihero (like every anti-antihero) is thus associated with (cruel, remorseless) authority, yet somehow at the same time this figure is associated with (free-floating, uncommitted) liminality. Perplexing!

Fredric Jameson suggests that the most difficult “term” to find in a Greimasian semiotic square is its “fourth term,” which he also calls the “negation of negation,” as well as a term representing something that is “neither A nor B.” Whereas the antihero demands both A [dominant discourse] and B [counter-discourse], and is therefore a semiotic schema’s “negative term” (because they reject the demand that they choose between A and B), the anti-antihero rejects both A and B; they negate, in Jameson’s formulation, the given social or ideological system in its entirety — discourse and counter-discourse.

In our G-schema, the anti-antihero paradigm is the fourth of four vertices from the schema’s first [it’s red, in our chart above] semiotic square; and yes, Jameson is right — it’s tricky to puzzle out a semiotic square’s fourth term. Surfacing and dimensionalizing a G-schema’s fourth term (the anti-anti-hero) is very rewarding, however, because doing so reveals a semiosphere’s deep ideological limitations and “closures.” Revelatory!

In Casablanca as in every other semiosphere, the anti-antihero is a heterodox figure. No matter what sort of narrative the other characters in the story might inhabit, that is to say, the anti-antihero is starring in their own picaresque. (Or so they believe.) The anti-antihero is troubling and fascinating because they recognize that they’re a character in a story, a paradigm in a schema… and they reject the semiosphere’s strictures. They’re a critic, perhaps even a semiotic analyst of the narrative… not merely, or so they insist, a character in it. They may even come to believe, in their negation-of-negation hubris, and because they see what it all means, that they’re the author of the story in which they find themselves.

“I suppose you know what you’re doing,” says Casablanca’s anti-antihero at one point to this semiosphere’s antihero. “But I wonder if you realize what this means?” A succinct statement of the semiotically inclined anti-antihero’s POV.

As a critic and analyst of the story in which they find themselves, the anti-antihero is lucid, ironic, self-aware, amused by the semiosphere’s taken-for-granted norms and forms, its politics and pieties. In a literary sense, then, they’re uncanny — even monstrous. Like a monster, the anti-antihero troubles our sense of objectivity, they provoke uncomfortable reflections. One way to determine the fourth term, or anti-antihero paradigm, is to ask: Who’s the monster?

A story’s villain isn’t necessarily monstrous, not in the sense we mean here. Our anti-antihero isn’t Strasser. Nor is it Ferrari, though his sinister formality is a bit terrifying. We sometimes read that Louis Renault, the Prefect of Police in Casablanca, undergoes a transformation from cynicism to idealism over the course of the movie. But Louis isn’t cynical, exactly, nor does he become idealistic, exactly. He’s ironic, self-aware, politically uncommitted — a charming, amusing figure. He’s also a monster. Casablanca’s anti-anti-hero paradigm is: RENAULT.

In this, the final series installment, we’ll examine the thematic complexes governed by the RENAULT paradigm. But first, a few words about the actor who brilliantly portrays Renault.

Claude Rains (1889–1967), who grew up with a speech impediment and a Cockney accent, got his start acting in London theater. In 1916, while fighting in WWI, he lost 90 percent of the vision in his right eye from a gas attack. Perhaps this explains his perpetually sardonic expression? (Compare with the one-eyed, sardonic Peter Falk.)

After the war Rains invented the singular mid-Atlantic accent for which he’s fondly remembered today, relocated to New York, and became a Broadway star.

Rains would make his American film debut in James Whale’s 1933 adaptation of The Invisible Man. (A role memorialized in the Rocky Horror Picture Show theme song: “Michael Rennie was ill / the day the earth stood still, / but he told us where we stand. / And Flash Gordon was there / in silver underwear, / Claude Rains was the Invisible Man.”) He would go on to appear in two other major horror movies of the era: He plays Sir John Talbot (father of the werewolf) in Universal’s The Wolf Man (1941), and he’s the titular phantom in Universal’s 1943 Phantom of the Opera remake. He was, it’s fair to say, one of the great movie monster actors of the era.

In addition to Casablanca (1942), Rains would play prominent roles — most often, though not always, villainous — in such movies as The Prince and the Pauper (1937), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), The Sea Hawk (1940), Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941), Kings Row (1942), Now, Voyager (1942; the most famous of his pairings with Bette Davis), Mr. Skeffington (1944), Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946; for which he received his fourth and final Best Supporting Actor Academy Award nomination), The Lost World (1960; playing the science-fictional Professor Challenger), and Lawrence of Arabia (1962). In his final role, Rains would play Herod in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965).

I’d watch Claude Rains in anything.

Jonathan Lethem

VICHY PUPPET

The Casablanca anti-antihero’s VICHY PUPPET complex is diametrically opposed, in our schema, to the antihero’s EXPAT IDLER complex. Whereas Rick Blaine is consumed with reaping the benefits of the PEACE territory (as a neutral American, that is, profiting from his freedom to cross national borders — note how Renault describes Rick to Strasser, not so jokingly, as “a citizen of the world”), Renault operates in the WAR territory. He profits from others’ inability to cross national borders.

As a representative of the Vichy government, which at this point was nominally independent of Germany but in fact obligated to resist Allied actions, it’s Renault’s duty to police the borders and prevent refugees from the Nazis from fleeing to freedom. However, this puppet is not easily controlled; so he’ll help refugees flee… for a price. Money, or sexual favors.

The relationship of a semiosphere’s antihero and anti-antihero is always a very strange one. Because the antihero refuses to choose between what Jameson calls A and B [see above], the antiantihero recognizes in him a sort of kindred spirit. In an ideological divided semiosphere, they’re both neutrals. However, wanting both A and B is a very different sort of neutrality than wanting neither A nor B. Thus in any narrative featuring both these types, although these characters are often drawn together, attracted to one another in an almost magnetic fashion… they’re incapable of becoming true friends, nor are they even allies. They prowl around one another, able neither to break free from one another nor to join forces.

Casablanca explores neutrality. The “asymmetrical neutrality” of Vichy France (in which France was officially neutral, but effectively aligned with Axis interests). America’s neutrality, as refracted through Rick Blaine. But also neutrality in the semiotician’s sense of the term: a state in which the values of a semiotic square’s two opposing terms are absent… and what that absence reveals.

Let’s pause here to review the career of a real-life Louis Renault (1877–1944), one of the founders of Renault, one of France’s largest automobile manufacturing concerns.

During WWI, the real-life Louis Renault, like his fictional namesake (who tells Strasser that he was with the American troops “when they blundered into Berlin in 1918”), did his part for France: His factories contributed massively to the war effort. After the French capitulation in 1940, however, Renault put his factories at the service of Vichy France — and via Vichy, Germany. Over a period of four years, Renault manufactured 34,232 vehicles for the Germans. He’d later argue that by continuing operations he had saved thousands of workers from being transported to Germany. However, after the war Renault was accused of collaborating with the Germans. He was arrested in 1944, and died that year while awaiting trial.

PS: See the FERRARI installment for a discussion of the real-life Ferrari.

Early in the movie, when the swastika-adorned plane carrying Major Strasser lands, Renault — a French military officer appointed by Vichy as Prefect of Police in Casablanca — is the first to greet him. His ironic manner and double entendres trouble Strasser, who is (as discussed in the STRASSER installment in this series) ever vigilant for evidence of disloyalty to the Reich.

RENAULT: You may find the climate of Casablanca a trifle warm, Major.

STRASSER: Oh, we Germans must get used to all climates, from Russia to the Sahara. But perhaps you were not referring to the weather.

RENAULT: What else, my dear Major?

Renault feigns seriousness in investigating the murder of the German couriers, and the theft of their letters of transit — which is to say, the MacGuffin that gets the plot of Casablanca moving. Though he seems to tell Strasser what he wants to hear… his meaning is something else entirely.

STRASSER: By the way, the murder of the couriers, what has been done?

RENAULT: Realizing the importance of the case, my men are rounding up twice the usual number of suspects.

As we’ll realize, later, what Renault is actually doing is rounding up the usual suspects — one of the phrases made famous by this movie — i.e., conducting a superficial investigation. He obeys the semiosphere’s villain, but disobeys.

Alas for Ugarte, the murderer of the couriers, rumors of his guilt circulate swiftly. (No doubt because he’s been bragging, as we see him do when he meets with Rick.) Despite Renault’s efforts to apprehend nobody, then, he finds himself compelled to arrest Ugarte. Whom he warns Rick not to help.

RICK: I stick my neck out for nobody.

RENAULT: A wise foreign policy.

Like Ferrari, it amuses Renault to project America’s foreign policy — the United States formally entered World War II on December 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor; the movie is set a day or two before Pearl Harbor — onto the American expat Rick. In order to preserve some degree of French sovereignty and control over its empire (including the French Protectorate of Morocco, the largest city and commercial hub of which was Casablanca), Vichy France remained officially neutral. So Renault is congratulating Rick, and by extension Rick’s homeland, for being wised-up in the fashion of Vichy France. Being wised-up, in fact, is what antiheroes and anti-antiheroes have in common; only a sucker ever chooses between a semiosphere’s A and B.

Continuing this conversation in Rick’s office, Renault announces to Rick that Major Strasser will be at Rick’s Cafe that evening to witness the arrest. Again, here he seems more concerned about Rick’s wellbeing than he does about carrying out his Vichy-appointed duties. We’ll theorize why in a moment.

RENAULT: Rick, there are many exit visas sold in this cafe, but we know that you have never sold one. That is the reason we permit you to remain open.

RICK: I thought it was because we let you win at roulette.

RENAULT: That is another reason. There is a man who’s arrived in Casablanca on his way to America. He will offer a fortune to anyone who will furnish him with an exit visa.

As mentioned above, the anti-antihero is a critic as well as a character. In fact, so keenly aware are they of the structural underpinnings of the narrative in which they find themselves, we might even call them a semiotician. In this exchange, Renault is explaining to Rick the structural nature of their relationship. Renault anchors one end of the axis perpendicular to the semiosphere’s A/B (dominant discourse / counter-discourse) axis; Rick anchors its other end. Were the RICK paradigm to shift, on our chart, towards the FERRARI paradigm, i.e., by getting into the black market — selling exit visas — then the Casablanca structure would implode. Which Renault, at least as this juncture, doesn’t want.

During this exchange, the keen-eyed (or should I say, keen-eye) Renault notices how impressed the stoic, blasé Rick is to learn that Victor Laszlo, one of the leaders of Europe’s antifascist resistance, has arrived in Casablanca on his way to America. (Renault, too, finds Laszlo an impressive figure.) Unlike Ferrari, who wants Rick to be influenced by Laszlo — as discussed in the FERRARI installment — Renault suddenly recognizes another way in which Rick might upset the sociocultural structure of Casablanca. He’s now worried that the RICK paradigm may shift in the direction of the LASZLO paradigm — and thus cease to be an antihero.

Something else is revealed about anti-antiheroes, here. Although possessed of an almost godlike ability to perceive the structural nature of their semiosphere, and although they (monstrously) reject the semiosphere’s A/B… the anti-antihero is not the master of their own destiny. They work for the villain. Their ultimate loyalty isn’t to the villain, but they don’t want the counter-discourse to triumph either. As much as we may find him amusing and attractive, we must remember this: Renault is helping the Nazis.

RICK: Well, it seems you are determined to keep Laszlo here.

RENAULT: I have my orders.

RICK: Oh, I see. Gestapo spank.

RENAULT: My dear Ricky, you overestimate the influence of the Gestapo. I don’t interfere with them and they don’t interfere with me. In Casablanca, I am master of my fate. I am captain of my —

He stops short as his aide enters.

AIDE: Major Strasser is here, sir.

Renault starts to leave.

RICK: Yeah, you were saying?

This is an amusing moment — a bit of slapstick propaganda, mocking Vichy France via Renault. (Vichy may pretend to be neutral, and a sovereign state, but it’s under Germany’s thumb, Rick is pointing out.) It’s also a rare moment in which we see how uneasy the monstrous anti-antihero’s position always is. Much like Al Czervik, anti-antihero of Caddyshack, from Major Strasser Renault gets no respect.

When Rick is introduced to Strasser, Renault does everything he can to insist that Rick is no threat to the Reich, while at the same time subtly letting Rick know that he, Renault, is no mere patsy for the Gestapo. He peppers the conversation with digs at Strasser and the Reich, intended for Rick’s understanding only.

RENAULT: We are very honored tonight, Rick. Major Strasser is one of the reasons the Third Reich enjoys the reputation it has today.

The Reich’s reputation is a vile one, of course. Strasser, however, seems to miss this innuendo He picks up only on Renault’s use of the qualifier “Third.”

STRASSER: You repeat “Third Reich” as though you expected there to be others.

RENAULT: Well, personally, Major, I will take what comes.

I will take what comes. Required to state his loyalty to the Reich, Renault refuses to do so. Not in the noble manner of the counter-discourse paradigm, Laszlo, but in an ironic manner. He is a picaro.

As we’ve noted at several points previously in this series, Star Wars owes a great deal to Casablanca. We’ve demonstrated how the paradigmatic figures from each movie can be more or less mapped onto one another. It’s always going to be trickier to map two anti-antiheroes onto one another, however.… because a monster is monstrous in a very specific, unique, eccentric way. So Darth Vader, the dark enforcer of the Galactic Empire, would seem to have little in common with the suave Renault — though both are anti-antiheroic paradigms in their respective semiospheres.

However, just as Renault’s loyalty to the Third Reich is tenuous, so is Vader’s loyalty to the Empire. We learn this about Vader in the second and third installments of the original trilogy. And even in the first movie, it’s made clear that Vader isn’t entirely under the thumb of Grand Moff Tarkin. If he were, he wouldn’t go around choking Tarkin’s officers — as a display of his displeasure about their incompetence or disrespect. Or in the case of Admiral Motti, for the Imperial officer’s lack of faith in Vader’s religion.

Vader, like Renault before him, supports the narrative’s villain, and by extension the dominant discourse of the semiosphere in which he finds himself. But only for the time being. He will take what comes.

In Renault’s office, the following morning, even as Strasser attempts to threaten and coerce Laszlo, Renault’s interjection seems a subtle attempt to prevent Laszlo from making a deal.

STRASSER: You know the leaders of the underground movement in Paris, in Prague, in Brussels, in Amsterdam, in Oslo, in Belgrade, in Athens.

LASZLO: Even in Berlin.

STRASSER: Yes, even in Berlin. If you will furnish me with their names and their exact whereabouts, you will have your visa in the morning.

RENAULT: And the honor of having served the Third Reich.

The anti-antihero is always a neither/nor figure, poised between a given semiosphere’s A and B. In this scene, Renault neither offers Laszlo the slightest assistance nor does he want Laszlo to help Strasser and the Reich. Jameson describes a semiotic square’s fourth term as “the most critical position and the one that remains open or empty for the longest time.” What does Renault want? We’re all wondering.

By the way, in that scene in his office, Renault tells Laszlo, regarding Ugarte: “I’m making out the report now. We haven’t quite decided whether he committed suicide or died trying to escape.” It’s a villainous thing to say, and no doubt intended to make Strasser happy. But it’s also a telling admission, from this semiosphere’s anti-antihero, that he has confused his ability to perceive the semiotic structure of the narrative in which he finds himself with the ability to author that narrative. A fatal flaw for any and all anti-antiheroes.

That evening, at Rick’s Café Americain, Renault and Rick have a brief, very odd exchange.

RENAULT: Rick, have you got these letters of transit?

RICK: Louis, are you pro-Vichy or Free French?

RENAULT: Serves me right for asking a direct question. The subject is closed.

The fourth term, Jameson tells us, “discursivizes the ideological nature of cognitive activity.” Our imaginations have been colonized; by keeping us guessing, the anti-antihero reveals how ideology works. The difficulty Renault’s interlocutors experience, and which we viewers experience, illuminates the intellectual, moral, and psychological effort required to think beyond a sociocultural system’s seemingly natural, inevitable, and eternal constraints. We’re supposed to be confused by Renault.

That same evening, Renault sits down at Strasser’s table at Rick’s Café after two officers — French and German — got into a scrap over Yvonne. Again, Strasser challenges Renault’s loyalty to the Reich:

STRASSER: Captain Renault, are you entirely certain which side you’re on?

RENAULT: I have no conviction, if that’s what you mean. I blow with the wind. And the prevailing wind happens to be from Vichy.

STRASSER: And if it should change?

RENAULT: Surely the Reich doesn’t admit that possibility?

Renault is resolutely, unapologetically neutral — which is another word semioticians use to describe a semiotic square’s fourth term. The danger of a semiotic square is that it can merely reproduce ideology; its neutral term is where ideological limitations are exposed and broken. Which explains Renault’s contemptuous amusement every time Strasser attempts to enforce the Reich’s ideology; in this exchange, he tweaks Strasser for inadvertently admitting that the Reich is not inevitable and eternal.

Renault, the Vichy puppet, is this narrative’s monster. Like all the best literary and movie monsters, Renault offers Casablanca’s other characters the opportunity to process — or fail to process — the inhuman scale and logic of the semiosphere in which they’re trapped. The puppet wants them to know that they’re all unwitting puppets of forces — narrative forces — that they can’t detect or comprehend. Even Strasser himself, for a split-second in this scene, seems to catch a glimpse of this uncanny insight.

AMORAL HEDONIST

The Casablanca anti-antihero’s AMORAL HEDONIST thematic complex is diametrically opposed, in our schema, to the antihero’s CYNICAL HUSTLER complex. Whereas Rick reaps the benefits of the BUSINESS territory (i.e, as a nightclub and casino entrepreneur), Renault is consumed with the pleasures of the flesh. Despite his winsome charm, he is a ruthless predator.

We hear about Renault before we meet him. Early in the movie, when the police are arresting everyone in sight, someone explains to an English couple: “Two German couriers were found murdered in the desert… the unoccupied desert. This is the customary roundup of refugees, liberals, and — uh, of course — a beautiful young girl for Monsieur Renault, the Prefect of Police.”

In any semiosphere diagrammed by a G-schema, each “hybrid” paradigm (i.e., paradigms that “govern” thematic complexes in a semiotic schema’s adjacent territories) uses its unstable, dynamic positioning to its best advantage. In previous installments we’ve explored how Ferrari’s access to the BUSINESS and WAR territories, say, lead to black market profits. And how Laszlo’s access to the PEACE and PLEASURE territories make him such an inspiring leader; and how Rick’s access to the BUSINESS and PEACE territories make him (at the very end of the story) a ruthlessly capable anti-fascist fighter. Renault, for his part, deploys his status within the WAR territory to further his coercive activity in the PLEASURE territory.

When we first meet Renault in his role as amoral hedonist, he’s sitting outside Rick’s Café Americain — observing Rick hustle a drunken and outraged Yvonne into a taxicab.

RENAULT: How extravagant you are, throwing away women like that. Someday they may be scarce. You know, I think now I shall pay a call on Yvonne, maybe get her on the rebound, huh?

RICK When it comes to women, you’re a true democrat.

This is the first exchange between Casablanca’s antihero and anti-antihero, and it’s already dizzying. Despite their apparent friendliness, Rick has just called Renault a fascist — in every area, that is, besides his sex life. Also note the body language here. Renault’s leg is crossed invitingly towards Rick… but before sitting down, Rick swivels the chair so that it doesn’t face Renault. As noted earlier, magnetic attraction and repulsion are happening simultaneously.

In the register of decadent, amoral fin de siècle aesthete, Renault pries into Rick’s past:

RENAULT: I have often speculated on why you don’t return to America. Did you abscond with the church funds? Did you run off with a senator’s wife? I like to think you killed a man. It’s the romantic in me.

He continues in this register when he tells Rick that they’ll arrest Ugarte that night:

RENAULT: You know, Rick, we could have made this arrest earlier in the evening at the Blue Parrot, but out of my high regard for you we are staging it here. It will amuse your customers.

Rick plays it straight — he’s no amoral hedonist, despite the scene with Yvonne we’ve just witnessed.

However, as mentioned earlier, one thing that the antihero has in common with the anti-antihero is being resistant to the semiosphere’s norms and forms. Their discussion of Laszlo’s arrival in Casablanca therefore results in a wager:

RENAULT: This is the end of the chase [for Laszlo].

RICK: Twenty thousand francs says it isn’t.

They sit down to discuss the matter in earnest.

RENAULT: Is that a serious offer?

RICK: I just paid out twenty. I’d like to get it back.

RENAULT: Make it ten. I am only a poor corrupt official.

The wager is cynical, on Rick’s part. But Renault isn’t cynical; in fact, he criticizes Rick’s cynicism. He again tests Rick’s commitment to neutrality, here. He seems quite concerned, as an analyst of the Casablanca semiosphere, that Rick will abandon the antihero position… thus destroying the system.

RICK: Louis, whatever gave you the impression that I might be interested in helping Laszlo escape?

RENAULT: Because, my dear Ricky, I suspect that under that cynical shell you’re at heart a sentimentalist.

Rick makes a face.

RENAULT: Oh, laugh if you will, but I happen to be familiar with your record. Let me point out just two items. In 1935 you ran guns to Ethiopia. In 1936, you fought in Spain on the Loyalist side.

As a dashing antihero, Rick is an idol of sorts in Casablanca. Following Nietzsche’s advice, Renault is philosophizing with a hammer, here — sounding out this idol, apparently eager to topple it.

We first glimpse the difference between a BUSINESS-rooted character and a PLEASURE-rooted one when the two begin to talk about Laszlo’s beautiful young female companion — presumably, as far as they know, the activist’s mistress.

RENAULT: No matter how clever he is, he still needs an exit visa, or I should say, two.

RICK: Why two?

RENAULT: He is traveling with a lady.

RICK: He’ll take one.

RENAULT: I think not. I have seen the lady. And if he did not leave her in Marseilles, or in Oran, he certainly won’t leave her in Casablanca.

RICK: Maybe he’s not quite as romantic as you are.

Rick is hardboiled, immune (or so he believes) to female charm. We’ve already seen evidence of this in his interaction with Yvonne, and we’ve seen how Renault disapproves of such cavalier behavior.

Every conversation with Renault seems to begin in the WAR territory (like the preceding exchange, with Rick, about Laszlo) but then veer into PLEASURE. The same thing happens in an exchange with Strasser:

STRASSER (to Rick): Who do you think will win the war?

RICK: I haven’t the slightest idea.

RENAULT: Rick is completely neutral about everything. And that takes in the field of women, too.

Here, Renault is offering us his analysis of what’s wrong, not just with Rick, but with all antiheroes. Unlike the anti-antihero, who will take what comes, the antihero’s negation makes them bitter, lonely, weird.

Which brings us to the moment when Renault says to Ilsa: “Rick is the kind of man that… well, if I were a woman, and I were not around, I should be in love with Rick.” This throw-away line would inspire many academics and fans to speculate about a submerged homosexual attraction or at least strong homoerotic bond between these characters. Film critic David Thomson’s 1985 novel Suspects suggests that Rick and Renault become lovers after the film’s events; in a 1996 review, Roger Ebert would describe Renault as “subtly homosexual,” later amending that to: bisexual.

Fun stuff, no doubt! But I tend to see Renault’s line as further evidence of the strange (queer, if you will) structural attraction-and-repulsion between a semiosphere’s antihero and anti-antihero. Renault is indeed fascinated with Rick, even obsessed with him. Not as a would-be lover, but as a keen analyst of the dynamic tension holding the Casablanca semiosphere together. Why is there something, rather than nothing? From his privileged negation-of-negation position, Renault knows: It’s because of Rick.

Note how Renault comments on how Rick ought to behave vs. how he does behave. In this exchange from when Laszlo and Rick first meet, for example:

LASZLO (to Rick): Won’t you join us for a drink?

RENAULT (laughing): Oh, no, Rick never —

RICK: — Thanks. I will.

Rick sits down.

RENAULT: Well! A precedent is being broken.

And in this exchange, when Rick allows Jan to win a small fortune at the roulette table:

RENAULT: I am very happy for both of you. Still, it’s very strange that you won.

He looks over and sees Rick.

RENAULT: Well, maybe not so strange.

Renault keeps accusing Rick of being, beneath his blank affect, untroubled by emotion except by irritability (viz. Harrison Ford’s acting style, in every movie), a “sentimentalist.” This possibility is so troubling to Renault because the Casablanca semiosphere’s underpinning “corners” (that is, the four vertices of the semiotic square marked in red on our G-schema) require Rick to be unsentimental. He cannot care about Ugarte’s fate; he cannot love Ilsa. Sentimentality could pull him in either of these directions, disrupting the structure of the semiosphere over which Renault presides like a demiurge.

When Rick gets drunk, that first night, he says: “They grab Ugarte and she walks in. Well, that’s the way it goes. One in, one out.” Thus revealing, to us (and Sam), that Renault’s suspicions are correct.

Despite all of Renault’s efforts, the semiotic structure of Casablanca is about to change. Laszlo precipitates things by awakening Rick’s anti-fascist sentiments (as seen in the “Marseillaise” scene); and Strasser makes things worse by overreacting — and insisting that Renault shut down the Café Americain. “But everybody’s having such a good time,” Renault protests. His response to Strasser applies not merely to the nightclub but to the Casablanca semiosphere, where Renault is so comfortable, in general.

Renault’s wildly hypocritical justification to Rick, about closing the cafe, is one of the movie’s most famous lines.

The next morning, we find Rick (now Richard once more, though disguised as Rick; see the RICK installment) is in Renault’s office, trying to get him to free Laszlo. Failing in his initial attempt, he speaks to Renault in the only terms — amoral hedonism — that Renault will understand and take seriously.

RICK: Yes, I have the letters, but I intend using them myself. I’m leaving Casablanca on tonight’s plane, the last plane.

RENAULT: Huh?

RICK: And I’m taking a friend with me. One you’ll appreciate.

RENAULT: What friend?

RICK: Ilsa Lund. That ought to put your mind to rest about my helping Laszlo escape. The last man I want to see in America.

Richard’s ploy works. Renault will allow Rick to leave Casablanca… as an antihero. As a “neutral,” an amoral hedonist. In any semiosphere; they look to the antihero as a kind of mirror. They want to see themselves as a negation of A/B, not a negation of negation. It’s another anti-antiheroic fatal flaw.

Previously we’ve discussed how Humphrey Bogart plays two roles, in this movie: Richard and Rick. And we have to consider the possibility that he’s also playing “Ricky,” whenever he’s around Renault. A character who functions as a mirror held up to the anti-antihero, a figment of Renault’s imagination.

RENAULT: Ricky, I’m going to miss you. Apparently you’re the only one in Casablanca who has even less scruples than I.

RICK: Oh, thanks.

Renault tells Rick: “You know, this place will never be the same without you, Ricky.” Again, he’s referring not only to Casablanca the city but Casablanca the story.

This is where Casablanca should end. Or at least, this should be Rick and Renault’s final encounter. Instead, we get a sequence in which Rick coerces Renault into letting Laszlo and Ilsa escape, Renault manages to alert Strasser, Rick kills Strasser — and then Rick and Renault stroll off into the night together. “This is the beginning of a beautiful friendship,” and all that.

In his 1966 essay “Pish-Tush,” film critic Manny Farber complains that Casablanca “wrongly” became a classic. The movie is an example, he would have us understand, of “white elephant” art — i.e., a movie that mostly eschews personal vision and instead aspires to (what Farber describes in the 1962–63 essay “White Elephant vs. Termite Art,” as) the “burnt-out condition of a masterpiece,” thereby becoming little more (at the level of form) than “an expensive hunk of well-regulated area.”

I agree with Farber, of course, and I would argue that the movie’s ending is a crucial flaw that dooms Casablanca to “white elephant” status. If for no other reason than its sentimental suggestion that we should instantly forgive Renault’s collaboration (no matter how reluctant) with the Nazis, and his predatory behavior towards refugees – particularly attractive female refugees. Most fans and (middlebrow) movie critics have indeed forgiven Renault, over the years. Everybody loves a sympathetic monster.

There’s a nice piece of blocking in the final scene, though. Where Renault and Rick are back-to-back. We’ve been tantalized by the possibility that these magnetic opposites were going to connect; here, however, we see that they’re just as much repulsed by one another as they are attracted.

Renault also has a good line in the final scene — where he bitterly refers to “that fairy tale you [Rick] invented.” It’s a moment of comeuppance for the anti-antihero who’d hubristically imagined himself the author of his own story. Instead, he realizes, he was (if only briefly) a character in a story written by the antihero.

All series installments: FERRARI | LASZLO | STRASSER | ILSA | UGARTE | YVONNE | RICK | RENAULT.