Rick

This is the seventh of eight installments in the series CASABLANCA CODES. See also the 2020 series CADDYSHACK CODES.

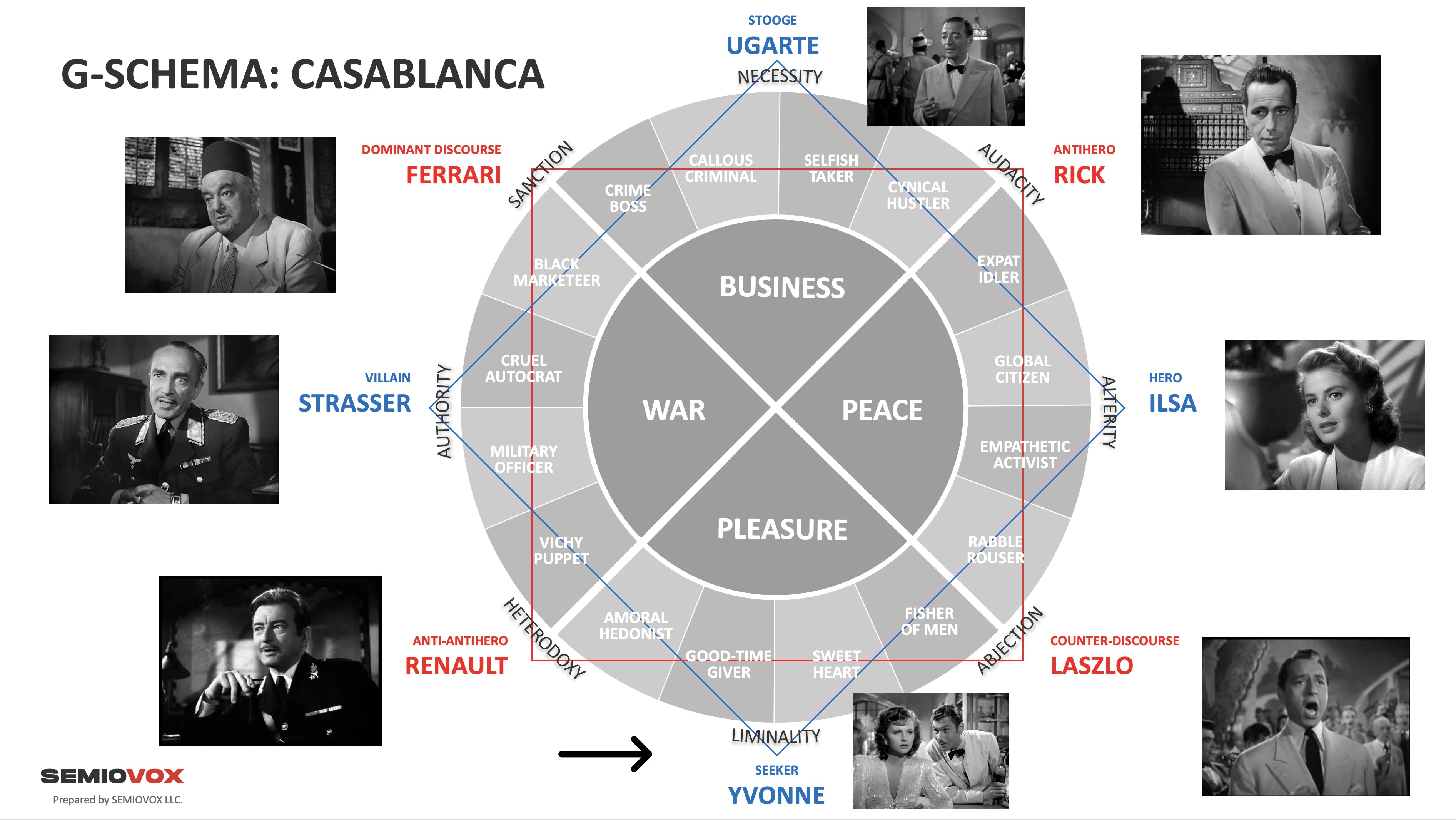

Thus far, the Casablanca semiosphere paradigms we’ve identified are: FERRARI (dominant discourse), LASZLO (counter-discourse), STRASSER (villain), ILSA (hero), UGARTE (stooge), and YVONNE (seeker). All of which is charted out via the Casablanca G-schema reproduced below.

We turn now to this semiosphere’s “antihero” paradigm… the third of four vertices from our G-schema’s first [it’s red, in our chart] semiotic square.

The antihero paradigm is “bordered,” according to our schema, by the stooge and hero paradigms. The antihero’s CYNICAL HUSTLER thematic complex abuts the stooge’s SELFISH TAKER complex, while the antihero’s EXPAT IDLER complex abuts the hero’s GLOBAL CITIZEN complex. Casablanca‘s antihero paradigm is thus more cynical, selfish, pragmatic than the hero paradigm, yet more idealistic, selfless, and noble than the stooge paradigm. A “very puzzling fellow,” as Laszlo says of this character. (“He is a difficult customer,” Ferrari will say of the same character to Ilsa and Laszlo. “One never knows what he’ll do or why.”) In this installment we’ll puzzle out what makes an antihero tick.

PS: Umberto Eco’s 1984 essay on Casablanca claims that Rick Blaine’s character embodies at least three “myths of the movies”: “the Ambiguous Adventurer, compounded of cynicism and generosity; the Lovelorn Ascetic; and at the same time the Redeemed Drunkard (he has to be made a drunkard so that all of a sudden he can be redeemed, while he was already an ascetic, disappointed in love).”

In Casablanca as in every other semiosphere, the antihero is an audacious figure. “Audacious people are unrestrained by the principles of decorum, morality, or common sense — they’re disrespectful, hotheaded, self-destructive,” one reads in The Adventurer’s Glossary, “and yet somehow we admire them for it.” Decorum, morality, and common sense dictate that a denizen of any given semisophere must choose between its dominant discourse and its counter-discourse. But an antihero has the audacity to refuse this choice; instead, they want it both ways. The antihero’s audacity is foolish, wrong, self-destructive. Which we can’t help but admire.

Which Casablanca character fits the description above? It’s Rick Blaine, the politically neutral, emotionally hardboiled, American expat owner of Casablanca’s swanky Rick’s Café Americain (and its illegal casino). The Casablanca semiosphere’s antihero is: RICK.

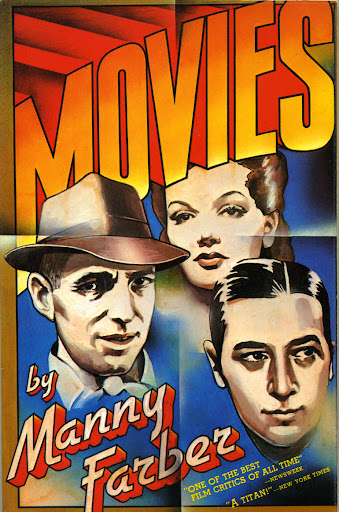

In this installment, we’ll examine the thematic complexes governed by the RICK paradigm. But first, a few words about the actor who portrays Rick.

Humphrey Bogart (1899–1957) was born in New York City and served in the US Navy during WWI. After acting on Broadway, he’d make his screen debut in 1928, going on to appear in supporting roles for more than a decade, regularly portraying gangsters — memorably, in The Petrified Forest (1936), Dead End (1937), and The Roaring Twenties (1939). His breakthrough came in Raoul Walsh’s High Sierra (1941). John Huston’s debut, The Maltese Falcon (1941), now considered one of the first great noir films, made him a major star.

Bogart’s first romantic lead role was as Rick Blaine, paired with Ingrid Bergman as Ilsa Lund in Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca (1942). Bosley Crowther would write, in his 1942 New York Times review of the movie, that the gangster-ish actor Bogart was likely cast in the movie “to inject a cold point of tough resistance to evil forces afoot in Europe today.” Casablanca would win the Academy Award for Best Picture; Bogart was nominated for Best Actor.

Howard Hawks introduced Bogart and Lauren Bacall in 1944. The three would go on to collaborate on To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946). Bogart and Bacall would also co-star in Delmer Daves’ Dark Passage (1947) and John Huston’s Key Largo (1948). Today, Bogart’s performances in Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) and Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place (1950) are considered among his best. He’d win an Academy Award for his role opposite Katharine Hepburn in The African Queen (1951), and he’d receive his third and final Academy Award nomination for The Caine Mutiny (1954). He’s often described, today, as the greatest male star of classic American cinema.

Bogart was a founding member and the original leader of the boozy Hollywood Rat Pack. He was also a liberal Democrat who organized the Committee for the First Amendment, which courageously opposed the the Hollywood Blacklist and the House Un-American Activities Committee’s harassment of Hollywood screenwriters and actors.

CYNICAL HUSTLER

Rick has persuaded himself, and most others in Casablanca, that he’s a businessman interested only in making a buck — via his nightclub and casino, Rick’s Café Americain. He’s a guarded and aloof figure, more interested in solving chess puzzles than schmoozing.

Before we lay eyes on Rick, we witness this dialogue:

CUSTOMER AT RICK’S CAFÉ: Oh, waiter.

CARL Yes, Madame?

CUSTOMER: Will you ask Rick if he’ll have a drink with us?

CARL: Madame, he never drinks with customers. Never.

He’ll be required to sit down — for a genteel interrogation — with Major Strasser, but that hardly counts. Tellingly, though, Rick will break his rule with Ugarte and Ilsa. Not coincidentally, the paradigms UGARTE and ILSA border the paradigm RICK in our schema. They are the poles of his magnet.

As analyzed in this series’ UGARTE installment, Rick’s exchange with Ugarte reveals the unequal dynamic (in any semiosphere) between the antihero and the stooge. The stooge truckles to the antihero, attempting to gain a modicum of respect… which is rarely granted.

Rick’s objection to Ugarte is, we suspect, idealistic: A former freedom-fighter, of sorts, Rick disapproves of Ugarte’s means of making a living. i.e., extorting money from hapless refugees. However, when Ugarte asks him about this, Rick maintains his facade as a businessman who cares only for profit.

UGARTE: You object to the kind of business I do, huh? But think of all those poor refugees who must rot in this place if I didn’t help them. That’s not so bad. Through ways of my own I provide them with exit visas.

RICK: For a price, Ugarte, for a price.

UGARTE: But think of all the poor devils who cannot meet Renault’s price. I get it for them for half. Is that so parasitic?

RICK: I don’t mind a parasite. I object to a cut-rate one.

Still seeking Rick’s respect, Ugarte then speaks to him in his own cynical, antiheroic way.

He takes an envelope from his pocket and lays it on the table.

UGARTE: Look, Rick, do you know what this is? Something that even you have never seen. Letters of transit never seen, signed by General de Gaulle. Cannot be rescinded, not even questioned.

Rick appears ready to take a look.

UGARTE: One moment. Tonight I’ll be selling those for more money than even I have ever dreamed of, and then, addio Casablanca!

“More money that even I have ever dreamed of” — a line riffed on by Han Solo in Star Wars — is Ugarte’s effort to ape Rick’s unapologetically mercenary persona. Ugarte entrusts the letters of transit to Rick, who conceals them atop Sam’s piano. At which point Ferrari, Casablanca’s crime boss and owner of a rival saloon, walks in. We’ve analyzed this scene in the series’ FERRARI installment; here’s the gist of it.

Ferrari and Rick are rival dons. Ferrari would like to buy the Café Americain — one assumes for the gambling operation, but also for the lucrative nightclub. He’d also like Rick to join him in the black market — i.e., smuggling refugees out of Casablanca for a price. Although Rick brusquely refuses both offers, the two men clearly have a certain respect for one another. This illustrates the relationship, in any semiosphere, between the dominant discourse paradigm and the antihero paradigm. Though at odds, in fact they depend on one another.

Despite Rick and Ferrari’s relationship as fellow players in the Casablanca semiosphere’s BUSINESS territory, though, the RICK and FERRARI paradigms are structurally at odds. Because they’re both hybrid paradigms; FERRARI is partly about WAR, Rick partly about PEACE. Even if Rick doesn’t want to admit this about himself, Ferrari certainly suspects it. Everyone in Casablanca, it seems, understands Rick’s heart better than Rick himself does.

As noted in the FERRARI installment, one suspects that this visit of Ferrari’s was an opening gambit. Ferrari no doubt suspects that Rick will at some point re-enter the struggle against fascism. Which is why he astutely makes an offer to purchase the Café Américain now, and also why he so blithely accepts Rick’s rejection. He’s just planting a seed, for the moment.

After concluding his exchange with Ferrari, Rick saunters over to the bar, where Yvonne — we understand that they are (casual) lovers — awaits him, bitterly and drunkenly.

YVONNE: Where were you last night?

RICK: That’s so long ago, I don’t remember.

YVONNE: Will I see you tonight?

RICK: I never make plans that far ahead.

As in his exchanges with Ugarte and Ferrari, here Rick seeks to persuade himself and everyone else that he is a hardboiled type — unemotional, cynical, callous. Rick sends a Yvonne home in a taxi, firmly but not unkindly. (He insists that the amorous employee he sends with Yvonne not dally at her apartment.) As noted in our YVONNE installment, an antihero is both fond of the seeker paradigm and condescending. See Ty Webb and Danny Noonan in Caddyshack; also Han Solo and Luke Skywalker.

As Yvonne’s taxi pulls away, we meet Captain Renault for the first time. He and Rick engage in some banter — which we’ll look at again in the RENAULT installment, as well as later in this installment… once we turn from the CYNICAL HUSTLER to the EXPAT IDLER complex. Even more so than Ugarte or Ferrari, Renault probes what I’ve suggested — in previous installments — is our antihero’s “Richard”/”Rick” dichotomy.

As they re-renter the building Renault informs Rick that Ugarte will be arrested there tonight.

RENAULT: If you are thinking of warning him, don’t put yourself out. He cannot possibly escape.

RICK: I stick my neck out for nobody.

RENAULT: A wise foreign policy.

Ferrari and Renault both make ham-fisted jokes, in this movie, about the expat American’s “policy” of neutrality. This is, after all, a propaganda movie set in December 1941, days — perhaps hours — before Pearl Harbor. But of course Ferrari is also commenting on the RICK paradigm’s hybrid positioning vis-à-vis the Casblanca G-schema’s BUSINESS and PEACE territories. The FERRARI paradigm, too, is a hybrid one — though it straddles the WAR and PLEASURE territories instead.

By the way, note that Renault often calls Rick “Ricky.” Yet another of our antihero’s personae — via which he permits Renault to believe that the two of them are more similar than they actually are.

Later that evening, when Ugarte is arrested, he makes a break for it… and begs Rick for help. Will “Richard” emerge, at this point, and intervene? Nope.

RICK: Don’t be a fool. You can’t get away.

UGARTE: Rick, hide me. Do something! You must help me, Rick. Do something!

Gendarmes rush in and grab Ugarte. Rick stands impassively as they drag him off.

UGARTE: Rick! Rick!

CUSTOMER: When they come to get me, Rick, I hope you’ll be more of a help.

RICK: I stick my neck out for nobody.

The cynical hustler facade remains intact.

After Ugarte’s arrest, Rick sits down for his interrogation by Strasser; we’ll discuss this scene in this installment’s EXPAT IDLER complex.

Just after Rick returns to the casino, Ilsa and Laszlo enter the Café Americain. While Laszlo meets with a fellow member of the Resistance, Ilsa (who has figured our that her ex-lover owns the place) asks her old friend Sam to perform “As Time Goes By.” Rick emerges from the casino, livid. “Sam, I thought I told you never to play…”

We’ve discussed this scene in the ILSA installment. Here, we catch a glimpse of the trauma that has transformed idealistic, romantic “Richard” into the hardboiled “Rick.” At first, we’re tempted to believe that Ilsa is the scheming adventuress (like Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon) Rick believes she is. The repartee between the two makes it seem that way:

ILSA: I wasn’t sure you were the same. Let’s see, the last time we met —

RICK: It was La Belle Aurore.

ILSA: How nice. You remembered. But of course, that was the day the Germans marched into Paris.

RICK: Not an easy day to forget.

ILSA: No.

RICK: I remember every detail. The Germans wore gray, you wore blue.

It’s after this encounter that Laszlo, puzzled, asks what sort of man Rick is. This is how an encounter with an antihero always feels: We don’t know quite what to make of them. Do they really believe they aren’t required to choose between a semiosphere’s dominant discourse and its counter-discourse? For how long can they get away with this suicidal high-wire act?

Rick’s hardboiled carapace is cracked by this encounter. That evening he drinks himself into a self-pitying stupor, longing for Ilsa to walk back into the club. In flashback, we see how deeply the two loved one another in Paris. It’s striking how sweet and optimistic Rick is, despite the imminent German occupation of Paris (and his possible arrest, as an antifascist arms dealer.) When Ilsa does return, late that night, Rick is savagely cruel — suggesting that she is a prostitute:

RICK: I heard a story once. As a matter of fact, I’ve heard a lot of stories in my time. They went along with the sound of a tinny piano playing in the parlor downstairs, “Mister, I met a man once when I was a kid,” funny. Tell me, who was it you left me for? Was it Laszlo, or were there others in between? Or aren’t you the kind that tells?

The next day, Ilsa — stung by Rick’s low opinion of her — tells him the secret she’d kept from him in Paris. She’s married to Victor Laszlo, and was at the time. This revelation softens Rick up even further. So much so that when the naive young refugee Annina approaches him for advice (should she sleep with Renault, in order to secure permission to leave Casablanca?), although he dismisses her with his usual hardboiled cynicism, in fact he assists her. Though not before a self-pitying “Nobody ever loved me that much.”

Rick resumes his mask of indifference when Laszlo (who’s been tipped off by Ferrari; see the FERRARI installment) approaches him about purchasing the letters of transit. However, when Laszlo rushes from the office into the nightclub at the sound of German officers triumphantly singing the “Wacht am Rhein,” and orders the orchestra to play the “Marseillaise,” Rick gives them the OK. A nod of the head that ends his career as a prominent Casablanca businessman.

At Strasser’s orders, Renault closes Rick’s Café Americain — perhaps forever. Rick isn’t ready to accept his transition out of the semiosphere’s BUSINESS territory and into its PEACE territory. He plans to keep paying his staff, out of his own pocket. And when he finds Ilsa in his apartment, desperate to persuade him to give up the letters of transit for Laszlo, he responds bitterly and selfishly.

ILSA: I know how you feel about me, but I’m asking you to put your feelings aside for something more important.

RICK: Do I have to hear again what a great man your husband is? What an important cause he’s fighting for?

ILSA: It was your cause, too. In your own way, you were fighting for the same thing.

RICK: I’m not fighting for anything anymore, except myself. I’m the only cause I’m interested in.

As discussed in the ILSA installment, Ilsa now tells Rick the harsh truth about himself. His cynical hustler persona, in her diagnosis, his hardboiled blankness, his neutrality, is a fragile snowflake’s over-compensation.

ILSA: You want to feel sorry for yourself, don’t you? With so much at stake, all you can think of is your own feelings. One woman has hurt you, and you take revenge on the rest of the world. You’re a — you’re a coward, and a weakling.

When she threatens Rick with a pistol, he invites her to put him out of his misery. This dramatic confrontation leads, at last, to their reconciliation. Ilsa explains why she abandoned Richard in Paris, and that she still loves him. Which is what he’d wanted to hear. But… “Richard” has reemerged now. And Richard, unlike Rick, isn’t a cynical hustler looking out only for his own selfish interests. He is more concerned with Ilsa’s “so much at stake.”

ILSA: I can’t fight it anymore. I ran away from you once. I can’t do it again. Oh, I don’t know what’s right any longer. You’ll have to think for both of us, for all of us.

RICK: All right, I will. Here’s looking at you, kid.

Although Richard continues to present himself as the cynical hustler Rick, we’ll discover that the paradigm RICK has shifted from the Casablanca semisophere’s BUSINESS territory into its PEACE territory. Closer to the ILSA paradigm… which ironically means that Richard will lose Ilsa forever.

I’ve mentioned before, in this series, that the Star Wars character Han Solo borrows a lot from Rick Blaine. We meet both characters day-drinking in a bar at the back end of nowhere, hiding from their past. They say they don’t want to get involved in resistance to an evil empire, and insist (again and again) that they only look out for themselves. Rick may allow Ilsa to believe that he’ll take her away from Laszlo, and he may lead Renault to believe that he’ll betray Laszlo… but Star Wars fans who fondly recall Han Solo flying away from the attack on the Death Star with his reward money, only to return at the last moment to rescue Luke from his pursuers, will suspect that Rick won’t go through with these selfish schemes.

Richard, now self-consciously adopting the persona of Rick/Ricky, visits Renault’s office in an effort to get him to free Laszlo. Failing in his initial attempt, he speaks to Renault in the only terms that Renault will understand.

RICK: Yes, I have the letters, but I intend using them myself. I’m leaving Casablanca on tonight’s plane, the last plane.

RENAULT: Huh?

RICK: And I’m taking a friend with me. One you’ll appreciate.

RENAULT: What friend?

RICK: Ilsa Lund. That ought to put your mind to rest about my helping Laszlo escape. The last man I want to see in America.

Richard persuades Renault to first release Laszlo, then re-arrest him at Rick’s Café Americain while Laszlo is picking up the letters of transit.

RENAULT: Ricky, I’m going to miss you. Apparently you’re the only one in Casablanca who has even less scruples than I.

RICK: Oh, thanks.

Still in the guise of Rick, Richard next visits the Blue Parrot to sell Ferrari the Café Americain. (See the FERRARI installment for analysis of this scene.) Ferrari, who has been working behind the scenes, or so it seems to me, to engineer Rick’s transformation into Richard, and who no doubt sees through Richard’s hardboiled facade at this juncture, has triumphed at last.

EXPAT IDLER

As an expat American who runs a nightclub and casino, and seems to have no interests other than drinking, casual womanizing, and solving chess puzzles, Rick at first seems a highly unlikely potential ally to Laszlo and Ilsa. However, we begin to hear rumors that there’s more to Rick than this hardboiled type is willing to admit (to others) or recognize (in himself).

Before we’ve even met Rick, when Renault tells Strasser that they can apprehend Ugarte at Rick’s, Strasser says: “I have already heard about this cafe, and also about Mr. Rick himself.”

Our first glimpse of Rick comes during a scene in which a German is attempting to force his way into the casino to gamble. Rick denies him entry — perhaps he’s not so neutral, after all. This is certainly Ugarte’s impression, though Rick won’t even let him voice his opinion.

UGARTE: When you first came to Casablanca, I thought —

RICK: — You thought what?

Ugarte laughs self-deprecatingly.

UGARTE: What right do I have to think?

However, once Ugarte confesses (not in so many words) that he’s murdered two German couriers, Rick is impressed. Not, however, by Ugarte’s newfound wealth. Despite his insistence that he only cares about profit, the ex-antifascist is pleased about the killing.

RICK: Yeah, I heard a rumor that those German couriers were carrying letters of transit.

UGARTE: Huh? I heard that rumor, too. Poor devils.

Rick looks at Ugarte steadily.

RICK: Yes, you’re right, Ugarte. I am a little more impressed with you.

We’re getting mixed signals, from Rick, in this exchange. It’s our first inkling that Rick isn’t as firmly anchored to this semiosphere’s BUSINESS territory as he might like to believe he is. It’s our first inkling that “Richard,” the swashbuckling do-gooder, lies buried deep inside “Rick.”

Backtracking slightly… When we first lay eyes on Rick, he’s studying a chessboard. One reads that the position on the board has emerged from a “French Defense”—which Rick is analyzing from Black’s perspective. That is to say, in this game he’s playing, Rick has sided with the French. Bogart, a talented chess player, no doubt came up with this subtle sight gag himself.

Later, Ferrari offers to purchase Rick’s club and casino. When Rick refuses, Ferrari responds: “What do you want for Sam?” As noted in the FERRARI installment, this is a grim moment — a White man seemingly offering to purchase a Black man. Rick replies: “I don’t buy or sell human beings.” This moment offers another suggestion that the hardboiled Rick has a conscience, and scruples… and that he may be an idealist and a champion of freedom.

Still later, after Yvonne’s taxi drives off, Rick and Renault chat. Renault teasingly interrogates Rick, attempting to ascertain whether Rick is truly as neutral as he seems to believe he is. Rick refuses to give him a straight answer.

RENAULT: I have often speculated on why you don’t return to America. Did you abscond with the church funds? Did you run off with a senator’s wife? I like to think you killed a man. It’s the romantic in me.

RICK: It was a combination of all three.

RENAULT: And what in heaven’s name brought you to Casablanca?

RICK: My health. I came to Casablanca for the waters.

RENAULT: Waters? What waters? We’re in the desert.

RICK: I was misinformed.

Moving into Rick’s office, Rick and Renault continue their conversation. Renault informs him that Major Strasser will come to the club that evening to witness the arrest of Ugarte. He also lets Rick know that Laszlo is in town — because he wants to judge Rick’s reaction. Will the former freedom fighter be impressed and thrilled that Laszlo, the Resistance leader, is here?

RENAULT: There is a man who’s arrived in Casablanca on his way to America. He will offer a fortune to anyone who will furnish him with an exit visa.

RICK: Yeah? What’s his name?

RENAULT: Victor Laszlo.

RICK: Victor Laszlo?

RENAULT: Rick, that is the first time I have ever seen you so impressed.

RICK: Well, he’s succeeded in impressing half the world.

RENAULT: It is my duty to see that he doesn’t impress the other half. Rick, Laszlo must never reach America. He stays in Casablanca.

RICK: It’ll be interesting to see how he manages.

RENAULT: Manages what?

RICK: His escape.

RENAULT: Oh, but I just told you. —

RICK — Stop it. He escaped from a concentration camp and the Nazis have been chasing him all over Europe.

RENAULT: This is the end of the chase.

RICK: Twenty thousand francs says it isn’t.

Rick was impressed, but quickly covered it up — and turned it into a cynical bet. Still in interrogation mode, Renault keeps pressing.

RICK: Louis, whatever gave you the impression that I might be interested in helping Laszlo escape?

RENAULT: Because, my dear Ricky, I suspect that under that cynical shell you’re at heart a sentimentalist.

Rick makes a face.

RENAULT: Oh, laugh if you will, but I happen to be familiar with your record. Let me point out just two items. In 1935 you ran guns to Ethiopia. In 1936, you fought in Spain on the Loyalist side.

RICK: And got well paid for it on both occasions.

RENAULT: The winning side would have paid you much better.

Rick has no witty response to this; Renault is correct. Even if he isn’t an idealist, a freedom fighter, and an avowed antifascist now, we understand, he certainly was once upon a time.

PS: In 1935, if someone “ran guns to Ethiopia,” they were secretly supplying weapons to the Ethiopian forces who were defending against an invasion by Fascist Italy, led by Mussolini. And in 1936, if an American fought in the Spanish Civil War on the “Loyalist side,” it means they’d volunteered to support the democratically elected government of the Second Spanish Republic against the right-leaning Nationalist rebels. These conflicts were a precursor to WWII.

Later, after Ugarte’s arrest, Rick is introduced to Strasser, who also interrogates him.

STRASSER: What is your nationality?

RICK: I’m a drunkard.

RENAULT: That makes Rick a citizen of the world.

RICK: I was born in New York City, if that’ll help you any.

STRASSER: I understand you came here from Paris at the time of the occupation.

RICK: There seems to be no secret about that.

STRASSER: Are you one of those people who cannot imagine the Germans in their beloved Paris?

RICK: It’s not particularly my beloved Paris.

HEINZE: Can you imagine us in London?

RICK: When you get there, ask me.

RENAULT: Ho, diplomatist!

STRASSER: How about New York?

RICK: Well, there are certain sections of New York, Major, that I wouldn’t advise you to try to invade.

STRASSER: Aha. Who do you think will win the war?

RICK: I haven’t the slightest idea.

Rick studiously maintains the impression — which he himself believes — that his idealistic, political days are behind him. He’s nothing but an expat idler, and a drunkard, these days.

STRASSER: You will forgive my curiosity, Mr. Blaine. The point is, an enemy of the Reich has come to Casablanca and we are checking up on anybody who can be of any help to us.

RICK (glances toward Renault): My interest in whether Victor Laszlo stays or goes is purely a sporting one.

STRASSER: In this case, you have no sympathy for the fox, huh?

RICK: Not particularly. I understand the point of view of the hound, too.

Rick isn’t merely being evasive. As an antihero, the RICK paradigm straddles the line between the dominant discourse (associated with WAR and BUSINESS, in this semiosphere) and the counter-discourse (associated with PEACE and PLEASURE). He refuses to choose.

However, Rick wants everyone to believe that he has made his decision. Leaving the table, he insists to Strasser that the Casablanca semiosphere’s BUSINESS territory is his only concern: “Your business is politics. Mine is running a saloon.”

His encounter with Ilsa, as previously noted, cracks Rick’s hardboiled carapace. When he gets blotto on his own, late that night, he poses an odd, drunken question to Sam.

RICK: Sam, if it’s December 1941 in Casablanca, what time is it in New York?

SAM: Uh, my watch stopped.

RICK: I bet they’re asleep in New York. I’ll bet they’re asleep all over America.

This is a particularly un-subtle propaganda moment in the script. But the point is, “Richard” is beginning to reemerge.

During the Paris flashback, we find out a little more about Rick.

A group of frightened French people cluster around a loudspeaker on a wagon. A harsh voice barks out the tragic news of the Nazi push toward Paris.

RICK: Nothing can stop them now. Wednesday, Thursday at the latest, they’ll be in Paris.

ILSA: Richard, they’ll find out your record. It won’t be safe for you here.

RICK: I’m on their blacklist already, their roll of honor.

Why is Rick on the Germans’ blacklist? We figure out that he’s an arms dealer, a gun runner. Meanwhile, Sam is singing: “It’s still the same old story / A fight for love and glory…”

ILSA: Was that cannon fire, or is it my heart pounding?

RICK: Ah, that’s the new German 77. And judging by the sound, only about thirty-five miles away.

The next day, i.e., back in Casablanca in 1941, once he sobers up Rick resumes his “policy” of selfish neutrality. When a German and a French soldier quarrel over Yvonne, Rick says: “Either lay off politics, or get out!”

On Laszlo’s second night in town, having been briefed by Ferrari, he approaches Rick about the letters of transit. Rick insists that he is unmoved by Laszlo’s antifascist efforts.

LASZLO: You must know it’s very important I get out of Casablanca. It’s my privilege to be one of the leaders of a great movement. You know what I have been doing. You know what it means to the work, to the lives of thousands and thousands of people that I be free to reach America and continue my work.

RICK: I’m not interested in politics. The problems of the world are not in my department. I’m a saloon keeper.

LASZLO: My friends in the underground tell me that you have quite a record. You ran guns to Ethiopia. You fought against the fascists in Spain.

RICK: What of it?

LASZLO: Isn’t it strange that you always happened to be fighting on the side of the underdog?

RICK: Yes. I found that a very expensive hobby, too. But then I never was much of a businessman.

Laszlo fails to persuade Rick through force of argument… but then he impresses Rick by courageously leading the orchestra in the “Marseillaise,” drowning out the German officers’ singing. Although we won’t realize this until the movie’s final scene, Laszlo has succeeded.

In their penultimate meeting, Laszlo makes a final effort to recruit Rick to the cause. (See the LASZLO installment for an analysis of the exchange, here — where Rick/Richard and Victor/Laszlo work at cross-purposes to one another.) Rick, one suspects, has already been converted to Laszlo’s cause. But he rallies for one last effort at hardboiled cynicism.

RICK: Don’t you sometimes wonder if it’s worth all this? I mean what you’re fighting for?

LASZLO: You might as well question why we breathe. If we stop breathing, we’ll die. If we stop fighting our enemies, the world will die.

RICK: What of it? Then it’ll be out of its misery.

LASZLO: You know how you sound, Monsieur Blaine? Like a man who’s trying to convince himself of something he doesn’t believe in his heart. Each of us has a destiny, for good or for evil.

RICK: Yes, I get the point.

LASZLO: I wonder if you do. I wonder if you know that you’re trying to escape from yourself — and that you’ll never succeed.

Like Laszlo, the critic Manny Farber is fed up with Rick’s effort to escape from himself via blank-faced stoicism.

Though a fan of Bogart’s — in various essays, he praises the actor’s “selfless hurt dignity” in 1941’s High Sierra, the “succinct repairs” he performs on a tank in Sahara (1943), the Acme Bookshop interlude in 1946’s The Big Sleep (an example of “curiosity flexing itself, spoofing, making connections to a new situation”), and in general the actor’s “taut, life-worn fluidity” — he doesn’t like what Bogart is doing in Casablanca. In the 1966 essay “Pish-Tush,” Farber derides the “static mannered acting,” the too-easy “scarred, sophisticated cynicism” of an actor who — because the movie’s director has set out to create a “masterpiece,” or what Farber would call “White Elephant art” — has been reduced to a “Great Star.”

Disparaging Bogart’s blank affect here, Farber renames the movie: Casablanka.

Bogart beat Farber to the punch. He himself once said: “The way to survive an Oscar is never to try to win another one. [T]oo many stars … win it and then figure they have to top themselves… [T]hey become afraid to take chances. The result: A lot of dull performances in dull pictures.”

From this point on, though we don’t realize it yet, Rick (or rather, Richard) is no longer trying to escape from himself. True to his promise to Ilsa, he is thinking “for both of us, all of us.”

At the airport, once Richard reveals his true plan, Ilsa protests. She wants to stay with him.

RICK: Inside of us we both know you belong with Victor. You’re part of his work, the thing that keeps him going. If that plane leaves the ground and you’re not with him, you’ll regret it.

ILSA: No.

RICK: Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon, and for the rest of your life.

Thanks to Ilsa’s tough-love approach, Richard is a changed man — emotionally intelligent, selfless, noble. Although a bit of a mansplainer.

Laszlo’s last words in the movie: “Welcome back to the fight. This time I know our side will win.”

There’s more. Richard kills Strasser, walks off into the night with Renault. But this is a better ending: what a drunken Rick might call a “wow finish.”

Next CASABLANCA CODES series installment: RENAULT.

All series installments: FERRARI | LASZLO | STRASSER | ILSA | UGARTE | YVONNE | RICK | RENAULT.